Discussion on Paper Currency among Russian Economists during the Great War (1914–1917) with Special Emphasis on Tugan-Baranovsky’s Contributions

- Publication type: Journal article

- Journal: Revue d’histoire de la pensée économique

2020 – 2, n° 10. varia - Author: Nenovsky (Nikolay)

- Abstract: World War I marked the final point of the continuous process of fiduciarisation of money, of the detachment from its substance, the final point of establishing « Russian type of ideal money ». Paper currency was a Russian tradition, since 1769, until the introduction of the gold standard in 1897. The war brought back the dominance of the paper currency. In this paper, I will consecutively dwell on: (i) the role of paper currency and loans during the war and the discussions among the leading Russian economists as regards the evolution of the monetary regime. I will then examine, (ii) Tugan’s business cycle (conjunctural) theory of the value of money associated with aggregate demand, and especially with the development of the model of money demand and its endogeneity, and finally (iii) on Tugan’s proposals for managed paper currency by controlling the exchange rate.

- Pages: 103 to 139

- Journal: Journal of the History of Economic Thought

- CLIL theme: 3340 -- SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES -- Histoire économique

- EAN: 9782406110644

- ISBN: 978-2-406-11064-4

- ISSN: 2495-8670

- DOI: 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-11064-4.p.0103

- Publisher: Classiques Garnier

- Online publication: 12-14-2020

- Periodicity: Biannual

- Language: English

- Keyword: World War I, Russian Monetary History, Paper Money, Russian Economic Thought, Tugan Baranovsky, Bernatzky

Discussion on Paper Currency

AMONG RussiaN ECONOMISTS

during the Great War (1914–1917) with Special Emphasis on Tugan-Baranovsky’s Contributions

Nikolay Nenovsky

Université de Picardie Jules Verne

CRIISEA – EA 4286

SU HSE, Moscow

There is a long-known law: war requires three things: first, money; secondly, money and, thirdly, money again.

Speech of the Russian Minister of Finance, P. Bark during the Allies’ meeting in St.-Petersburg in January 1917, Bark, 2017, v. 2, p. 300.

Contemporary war has taught economists many new things and much of what was considered impossible earlier today seems simple and comprehensible

Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 131.

104Introduction

On Russian paper currency

The war economy assigned new goals and means to the economic policy. The goal was victory and survival of the nation and the main economic task became the financing of war. The state and planning became leading economic institutes and the market and sound public finances remained in the background. Paper currency became the main source of financing war expenditures. As a final result there was a dramatic melting of the gold reserves and a growing budget deficit. The printing of paper currency became inevitable and its depreciation was a logical consequence2.

World War I marked the final point of the continuous process of fiduciarisation of money, of the detachment from its substance, the final point of establishing « Russian type of ideal money ». Paper currency was a Russian tradition, dating back to the leather (or meha currency3), which underwent continuous depreciation of silver and copper coins. Since 1769, until the introduction of the gold standard in 1897, paper currency passed through two large epochs – that of assignats (assignations, ассигнации) (1769-1839) and that of credit roubles (кредитныерубли) (1854-1897).

The war led not only to the dominance of the paper currency, it undoubtedly prompted the reaction of Russian economists about the future evolution of monetary regimes. Before the war the following three trends can be differentiated.

The pre-revolutionary Russian economists such as B. Goldman, I. Kaufman, N. Bunge, A. Guryev, M. Kashkarov, I. Ozerov, P. Migulin, A. Miklashevsky, P. Nikolskiy, and I. Tainov among others (as well as some foreign connoisseurs of Russia, such as H. Storch, A. Wagner, 105E. Lorini and H. P. Willis), focussed their attention on paper currency and its Russian peculiarities4. They considered paper currency to be a deviation from the norm, a currency pathology. Those authors dedicated numerous works to the Russian currency, most of which were in line with the metallic monetary tradition, according to that the paper currency was only a representative of metallic money and had no individual value. Any deviation from the norm, i.e. from the metal-backed paper currency was harmful and temporary. That consensus about the return to metallic money was in radical contrast with the background of the almost permanent reign of paper currency in Russia.

On the other hand, along with the metallists, there was also another group of scholars (in most cases not professional economists) including interesting authors not always taken seriously in the academic circles such as N. Karamzin, N. Danilyevsky, N. Turgenev, S. Sharapov (Talitsky), G. Butmi, A. Nechvolodov, who considered paper and fiduciary money a typical Russian, orthodox and monarchic institution5. That group of authors is important from an analytical point of view and from the perspective of comparative monetary history, because they brought to the foreground the specific features in the Russian monetary tradition.

Besides those two groups, a third group emerged which included prominent economists well integrated in the academic and economic community. They believed that the regime of paper currency was a radically new universal stage in the monetary evolution (M. Tugan-Baranovsky, A. Rykachev, M. Bernatzky, etc.). They were inspired by the Austro-Hungarian monetary reform of managed paper currency that started in 1892, was supported by law in 1899, and lasted until 1911-1912. Particularly in the wake of a war, those economists were critical of the orthodox monetary theory6.

106Of particular interest is the Ukrainian economist M. Tugan-Baranovsky (1965-1919) (referred to below as Tugan). He was well known beyond the boundaries of Russia due to his works on the economic cycle (see for ex: Hansen, 1964, p. 277-322) and Marxian capitalist reproduction, on the evolution of the Russian factory, industry and cooperatives, etc. He also developed a model of a future social (socialist) economy based on a theoretical synthesis of the labour theory and marginal utility theory, see for survey (Allisson, 2015) and (Allisson, 2011). Relatively less known are his publications on monetary theory and policy (Graziani, 1987; Koropeckyj, 1991; Barnett, 2001). Most of those were written during the war and were not translated7. There is no doubt that Tugan would have developed his monetary ideas were it not for his premature death in 1919 on his way as an Ukrainian representative to the Versailles Conference8.

In this paper, I will consecutively dwell on (i) the role of paper currency and loans during the war and the discussions among the leading Russian economists as regards the evolution of the monetary regime. I will then examine (ii) Tugan’s business cycle (conjunctural) theory of the value of money associated with aggregate demand, and especially with the development of the model of money demand and its endogeneity, and finally (iii) on Tugan’s proposals for managed paper currency by controlling the exchange rate.

107I. PAPER CURRENCy or LOANS: Discussions among

the leading Russian Economists on war financing

Russia’s readiness for war has been the subject of analysis of Russian economists since the end of the 19th century9, and particularly after the defeat in the Russian-Japanese war in 1905 (Bliokh, 1898; Migulin, 1904, 1905). The Balkan Wars (1912-1913) gave a new impetus to those publications, and WWI became the subject of a study of a huge number of works most of which had no serious analytical value. The publications included a number of economic studies which analysed the costs of war, its financing, and the consequences for Russia’s monetary system and public finances10.

Problems pertained to the lack of readiness for war, to the comparatively high costs (compared to rivals and allies), as well as to the limited domestic resources such as fiscal base and savings as well as the loss of revenues due to the introduction of the « dry law ». Russian economists argued on the difficulties on introducing new taxes which (see the Memoirs of the Last Minister of Finance, Bark, 2017), and also on the need to obtain foreign loans from France and England. The special subject of analysis was the transfer of gold reserves to England and the granting of a fictitious credit from there (Sidorov, 1960)11.

Another subject of discussion was the issue of treasury bills of low denomination (fiscal currency) and the most popular proposals were those of M. Bogolepov and P. Migulin. For instance, Migulin’s idea aimed to reduce the government debt and to « release » gold reserves to serve as a cover for issuing a new portion of banknotes. This proposal, however, was rejected following a debate in which actually all participants strongly opposed them supporting the metallic and metal-backed paper currency (except in part M. Bernatzky and, above all, Tugan) (see the discussions in MF, 1915, as well as in Bark’s Memoirs, 2017).

108Standing out among the publications during the war was the collection entitled War Loans. A Collection of Articles (1917) (WL), ed. by Tugan, with authors prominent Russian economists such as M. Bernatzky, M. Bogolepov, V. Idelson, I. Kulisher, V. Mukoseev and M. Fridman12. Two other collective works on the subject are noteworthy, also edited by Tugan – on the economic problems of war namely – (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1914b, and 1915), as well as the forewords of Tugan in Tugan-Baranovsky (1914a and 1917b).

The WL collection contains the main appeal of leading economists for limiting the issue of paper treasury notes and non-convertible banknotes and for a return to the principles of the gold standard. Those were the positions of all participants, with light nuances of the standpoints of M. Bernatzky and Tugan13. According to the editor:

The emission of paper currency represents, unfortunately, a condition sine qua non for financing a war of such huge proportions as modern warfare. Countries which are backward in their economic development, due to the scarcity of capital, are not at all able to wage significant wars, except in the case of releasing new paper currency. The number of these countries includes Russia as well. […] However, the emission of paper currency as a source of financing war is a highly dangerous financial resource, which can only be used as a last resort, in the absence of any other means for covering military costs (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917b, p. 7-8).

But:

The thing is that, the more paper currency is put into circulation, the more difficult it is to switch over after the war to the normal conditions of money circulation (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917b, p. 21).

In order to stop the issue of paper currency, all authors spoke in support of domestic loans as an important instrument which had not been used efficiently that far. Russia’s fiscal capacities were limited, and external loans were virtually impossible. According to the authors, there 109were significant possibilities of using domestic loans. Tugan estimated them at 4–5 billion roubles of completely free resources, around 14-15 billion roubles of savings deposited in banks and savings funds, as well as other free capital14.

As regards that plan, the article « Military Loans in Germany » by the economic historian J. Koulisher dwelt on the four loans subscriptions from the German government, their techniques (the role of the Treasury in paying for the military supplies), as well as a review of the positions of leading German economists. His comment is worth mentioning:

The best evidence that Germany was preparing for war was its economic literature. At the time when in the French and English works the starting point was always the state of peace, the peaceful exchange among the European nations – the Germans proceeded in their studies from two different, equally possible, prerequisites: the time of peace on the one hand, and the state of war, a future war which they considered to be close on the other hand. (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917b, p. 26)15.

For his part, the future Minister of Finance in the Provisional Government M. Bernatzky studied the relationship between money circulation and loans (Money Circulation and Loans), in which he offered important foresights. According to the author:

The more unsuccessful the loans are, the more the money circulation of Russia will be disrupted, the lower the Russian rouble will fall (Bernatzky, 1917, p. 102).

The study of V. Mukoseev, published in the collection is perhaps the most systematic statistical study of Russia’s military loans in the first 2-3 years of the war. Mukoseev studied the first six loans, 1914, 1915 110(three loans) and 1916 (two loans) as well as their relationship with the paper currency circulation (Mukoseev, 1917, p. 142-195)16. Similarly, to most of his colleagues, Mukoseev also believed that monetary financing was harmful and disorganized the economy, but it was inevitable and its damaging effect could only be minimized by expanding the base of domestic loans.

Today’s war is being waged on such a gigantic scale that the theoretical issues about the advantages of this or that way of covering military expenditure are largely devoid of substance. The requirements of war as regards the national economy are so great that to meet them at the expense of only one source of financing is totally unthinkable, that’s why it is equally necessary and unavoidable to use all available resources of the country. […] Obviously the very scale of today’s war as a definite economic phenomenon is not in accord with the available concrete conditions of the economic and financial life in Russia. That war which emerged economically in countries of high capitalist culture is more suitable for those countries than it is for the poor Russian state. […] Lorenz von Stein said the following aphorism: « Great debts are made by Great states, and then when there are Great world events ». Today this aphorism can be fully applied to Russia. (Mukoseev, 1917, p. 149, p. 188-189).

The interrelation between the two sources of financing, – domestic loans and the emission of paper currency was of utmost importance. Part of domestic loans were short-term liabilities discounted by Gosbank directly or through private banks (Lombard discounting). That meant an increase of paper currency. According to the authors of that book (WL) prior to the beginning of the February Revolution, Gosbank was granted the right to release uncovered credit notes to the tune of 6,600 mln. roubles. See also the detailed description of those limits of the emission law for 1914 and 1915 in Mihailov (1916, p. 30-35).

The authority of the financial service of the state in the face of its main paying authority (the Treasury) issued treasury bills (acceptances), their form and currency had already been determined by special laws. Those policies were then submitted to Gosbank and were accounted for along with the term trade receivables, and their amount was determined by the volume of expenditure made, if there were no other sources for those costs. Amounts equal to those policies were assigned to the current account of the Treasury and were subsequently spent according to the current needs. […] Obviously, 111Gosbank had to emit paper currency for those sums, i.e. each time to expand the circulation of credit notes, depending on the entry of further volumes of treasury bills, and thus – moving farther from the boundary that separated it from the healthy money circulation. […] Gosbank was interested so that the assistance provided to the government should not reach particularly large size if it (Gosbank) accepted for discounting treasury bills of huge sums. Then the money circulation would suffer greatly, and with it the national economy and the country as a whole. […] That large, moving amount of paper currency represented the working capital of war of its own kind and served as a feeding fund for the military loan emission (Mukoseev, 1917, p. 180-181; p. 191-192).

Therefore, according to Mukoseev, everything possible had to be done to increase the share of the 2.5% treasury bills disposed through the banking system. The government actually made attempts to that effect although the results were too modest (Table 1).

Tab. 1 – 5% of short-term debt issue (in %).

|

Through Gosbank |

At the open market (banks, etc.) |

Total |

|

|

As of December 1, 1914, |

82,0 |

18,0 |

100,0 |

|

As of December 1, 1915 |

83,1 |

17,9 |

100,0 |

|

As of May 1, 1916 |

72,9 |

27,1 |

100,0 |

|

As of October 1, 1916 |

60,3 |

39,7 |

100,0 |

|

As of December 1, 1916, |

68,2 |

31,8 |

100,0 |

Source: Mukoseev, 1917, p. 182-183. (for 1915 the total amounts 101%, apparently error)

During the period of the Interim Government i.e. from March 1 to November 1 1917 the emission rose by 6 412, 7 mln. roubles (Yurovsky, ed., 1926, p. 11). Apart from the credit notes « exchange stamps » were released in 1917 to the tune of 95,8 mln. roubles and exchange treasury notes for 38,9 mln. roubles. The Interim Government emitted two kinds of paper currency – the so called « dumskie » (large denominations, 250 and 100 roubles) and « kerenki » (exchange treasury notes of 20 and 40 roubles). The seigniorage (money income) during the period of the Provisional Government drastically dropped and the Treasury actually managed to gain 1,735 billion roubles out of the emitted 6,5 billion 112roubles. The money supply in real terms was melting fast. Mukoseev summarized Russia’s war debts in late 1916 (Table 2).

Tab. 2 – Russia’s war debts as of December 31, 1916 (in mln. roubles).

|

1914 |

1915 |

1916* |

Total |

|

|

Domestic |

||||

|

Bond lending |

500 |

2 500 |

5 000 |

8 000 |

|

Treasury notes |

300 |

550 |

850 |

|

|

Short-term treasury bills, liabilities Total Including At the expense of issuing paper currency (Gosbank) Other means (private subscription, banks, etc.) |

800 1 600 653 (40, 8%) 947 (59,2%) |

3 200 6 250 2 608 (42,2%) 3 608 (57,8%) |

5 775 10 775 3 434 (32%) 7 34 (68%) |

9 775 18 625 6 729 (36,1%) 11 896 (63,9%) |

|

Abroad** |

491 |

6 694 |

2 225 |

9 410 |

|

Total |

2 091 |

12 954 |

13 000 |

28 045 |

Source: (Mukoseev, 1917, p. 191). *Preliminary data; **loans from abroad were denominated in pounds, franks and dollars. Loans in 1914 and 1915 are described in details in Mihailov (1916, p. 17-18). There are some small errors, for 1915 the total debts should be 12 944, and for the three years the total debts should be 28 035.

V. Mukoseev also discussed the specifics of the collateral of the Russian paper currency17. It concerned the transfer of part of the gold reserves in England 18, which served as a collateral not only for the debts of the government owed to England, but also for the paper currency (the position « gold abroad » appeared in the balance sheet of Gosbank). That was in fact a debit account of the Treasury, but disguised as the credit account of Gosbank. Overall, that way of backing was fictitious and artificial. The gold exports to England and foreign loans were described in details in the Memoirs of Minister of Finance Pyotr Bark (Bark, 2017) and 113(Barnett, 2001, 2005). Later, in 1926, in the book entitled Our Currency Circulation ed. by L. Yurovsky (and citing the study of American economist (Fiks, 1925 [1924]), it was noted (quote verbatim):

The expansion of the bank’s emission right however during that period was carried out not only by government acts. As is known, the State Bank’s gold fund, serving as a collateral for the emission of credit notes, was treasured not only in Russia but also abroad. « Gold abroad » was that part of the Fund for guaranteeing the emission which was treasured in the credit institutions overseas and was used by the Bank for external payments and for launching initiatives for the maintenance of the rouble rate. However, since the beginning of 1916, the nature of those amounts, marked as « gold abroad », changed significantly. They included the credits granted to Russia by the English Treasury, regardless of whether those credits were actually used or not. The inclusion of those credits resulted in a significant increase in the gold collateral of credit notes. […] It is also noteworthy that during the period under review there were shipments of gold from the fund of the State Bank in England. Those shipments were the result of the agreement between the Russian and the English governments. In October 1914 gold to the tune of 75 million roubles was sent to England, in May 1916 gold to the tune of 54, 5 million roubles and in November 1916 gold to the tune of 94,5 million roubles19. Thus, the overall increase of the gold fund was fictitious. The increase of the emission collateral, which was at the expense of the increase of the “gold abroad” position expanded the emission right accordingly. As of March 1, 1917, the emission of credit notes was as follows:

Tab. 3.

|

Collateral of Emission |

Emission right |

Credit notes in circulation |

||

|

Gold in Russia |

Gold abroad |

Total |

||

|

1,476 mln. r. |

2,141 mln. r. |

3,617 mln. r. |

10,117 mln.r. |

9,975 mln. r. |

Source: Yurovsky, ed., 1926, p. 6-7.

While paper emission rates were relatively reasonable during the first two years, in 1916 the monthly increase of the money emission was 3%, and in 1917 when the situation was definitively out control, the increase in some months reached 22-23% (Bogolepov, 1924, p. 15; Falkner, 1924). 114On the eve of the Bolshevik Revolution, the money circulation amounted to about 20 billion roubles (i.e. 10 times growth) and the prices rose 7.5 times20. In comparison, paper issue for the first two years in Russia amounted to 3,718 million gold roubles, in France – 2,774 million gold roubles, in Great Britain – 707 million gold roubles, in Germany, 2,897 million gold roubles. (Mihailov, 1916, p. 34)21. A. Mihailov pointed out the sources of financing the war (Table 4)22.

Tab. 4 – Sources of financing the war as of January 1, 1916.

|

Domestic loans |

Credit operations on foreign markets |

Short-term liabilities of the treasury on the domestic market |

Treasury notes |

Other |

|

|

To Gosbank |

On the open market |

||||

|

26,6% |

17,4% |

31,5% |

7,2% |

8,3% |

9,0% |

Source: Mihailov, (1916), p. 18.

Leading Russian economists, as has been pointed out unanimously supported the return to the metallic money. Two examples. The first one is the general rejection of the proposal of Prof. Migulin (member of the Finance Committee with the Finance Ministry) in 1915 for the issue by the Treasury of non-backed treasury notes of small denominations, whose eventual acceptance would have allowed a gold reserve to be released for a larger banknote emission (MF, 1915). The idea was opposed by I. Kaufman, M. Bogolepov, A. Guryev, A. Vishnegradsky, M. Friedman, partially supported by M. Bernatzky and in theoretical terms only by Tugan. Eventually, the Minister of Finance P. Bark rejected the project (Bark, 1915, p. 1-23)23.

The second example are the discussions at the end of the war, 1918, within the Foreign Trade Department with the Central National Industrial Committee in St. Petersburg, collected as scientific papers 115Issues of Currency Circulation, (Lomeyer, 1918). The collection includes seven reports, projects for the post-war monetary organization and the debates on them. Despite the various technical proposals (e.g. for the first time there was a proposal for the parallel circulation of the old decreed money and the new, metallic and convertible currencies-backed money24), especially for the transition period, there was consensus on the return to metallic or metal-related paper currency. M. Bernatzky, A. Guryev, A. Zak, V. Ziva, N. Lodizhevskiy, A. Lomeyer and F. Menkin supported that idea.

Against the background of that unanimity the fundamentally different position of Tugan on the future development of the Russian monetary system stood out. And while for Russia Tugan’s views can be defined as rarity among professional economists, in the developed Western countries not only the practical possibilities were discussed, but also the theoretical foundations of an active management of paper currency. Tugan developed a theory commensurate with the theoretical achievements of economists from Western Europe and the United States (Graziani, 1987). He made a gradual progress in his theoretical quests and in his last book (Paper Currency and Metal, 1917) he provided a systematic theoretical model. That book has not been the subject of a comprehensive analysis except (Koropeckyj, 1991; Graziani, 1987; Barnett, 2001, 2005) and the Ukrainian authors (Zlupko, 1998; Kuchin, 2006; Lopukh, 2014 and Orlik, 2017).

II. Tugan – The Theory

of the Value of Paper currency

II.1. Role of Economic Conditions (Business Cycle),

Aggregate Demand and Money Demand

Unlike most pre-revolutionary economists, including a number of Marxists (who considered that Marx was a supporter of metallic money), Tugan was among those who thought that the return to metallic money was 116impossible. The value of money in the future would not be determined by metal, but by the actively manageable and non-convertible paper currency.

Tugan was well versed in the theoretical approaches to determining the value of money (the reciprocal one to the general price level) – (i) the quantity theory (where the value of money was a function of its quantity, as well as of other factors in the Fisher’s version) and (ii) the demand theory, where the value of money was a function of the dynamics of the aggregate demand and supply. This second approach came from the books of T. Tooke (called the « commodity » approach) and gained popularity in the works of K. Wicksell, J. Lescure, etc. Tugan was also familiar with the third approach, where the value of money was deduced from the principles of the marginal utility of gold (the « regression theorem » of L. Mises).

An evidence of Tugan’s interest in those approaches were the articles he selected in the series New Ideas in the Economy, and especially the fourth issue dedicated to The Dearness of Life (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1914a). Tugan selected translated articles related to the above-mentioned approaches – (i) the quantity theory and Fisher’s approach (article of S. Margolin) – (ii) the demand approach (articles of J. Lescure, A. Zalts and V. Egenshweller), as well as (iii) the article by L. Mises, which had a critical view as regards the quantity theory25.

In fact, Tugan had long been aware of the limited possibilities of the quantity theory in explaining the general price level and the value of money26. He was also aware of the underdevelopment and the theoretical rudimentarity of the alternative approach, that of the aggregate supply and demand. Tugan blamed Tooke for refuting any individual factors for the value of money which could be found on the side of money (Tugan, 1917a, p. 9).27 He tried to offer a new, considerably more tenable theory without completely denying the usefulness of certain principles of the quantity monetary approach.

117The new theory of money was set forth in Tugan’s Paper Currency and Metal (1917a) which came out at the same time as the WL collection. The monograph was completed in October 1916, and in the words of the author himself, it included texts already published in various journals. In that work Tugan discussed the fundamental problems of the monetary theory.

Tugan started with a critical description of the two basic approaches in monetary theory – the quantity theory of money and that of demand, the commodity theory of money (formulated most clearly by T. Tooke). With certain simplifications, while in the first theory the volume of money determined the general price level, in Tooke’s theory it was just the opposite – commodity prices in the end determined the amount of money. Tugan accepted as a starting point the criticism of the quantity theory (in Fisher’s version), which was used before him by (Wicksell, 1898) and (Lescure, 1913)28. He mobilized a number of empirical evidences from the history of the metallic currency regime, as well as from the long periods of paper currency in Austria and Russia29. According to Tugan, the quantity theory was only applied in a regime of non-convertible paper currency.

Essentially the demand approach was not theoretically elaborated – the money supply was a passive reflection of relative prices, supply and demand. The value of money was not determined. The lack of « theory in Tooke » led to the fact that the empty space was occupied by the quantity theory. Tugan was explicit on the point that both theories were inadequate in theoretical terms:

The two competing theories of the value of money – the « commodity » theory of Tooke and the quantity theory – cannot be acknowledged as a satisfying solution of the problem of the value of money (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 28).

The new, called by Tugan, a « business cycle, business conditions (conjuncture / конъюнктурная теория) theory of the value of money »30, 118offered a system of circular cause and effect relations linking the real and monetary sectors (set forth in Chapter III, Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 37-52). The demand approach was elevated to the macroeconomic level, where the concept of economic conditions became of major importance. For Tugan it was something broader than demand, and synthesized in itself the complex behavioural relationships of economic agents. The value of money became a function of the business cycle movement and completely independent from the concrete relative prices31. The value of money could not be explained by the labour theory of value, nor by the theory of marginal utility which were essentially microeconomic theories. The new theory was macroeconomic and the value of money was dissociated from metal. That made the independent existence of paper currency possible. Tugan formulated that as follows:

The general level of prices, in other words, the value of money (these two economic concepts correspond to the same economic phenomenon) is therefore determined by completely different factors than those of the relative commodity prices (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 13).

The value of money is an entirely social phenomenon, a product of disorderly unconscious national and economic processes. That is why the general theory of the value of goods cannot explain the value of money (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 39).

Or in other words:

We can emphasize once again that the value of money is a phenomenon of a completely different order, compared to the value of any commodity. The value of a commodity is more or less a result of the conscious assessments of individuals consuming and producing a definite commodity. On the contrary, the value of money is a completely unconscious disorderly product of the general conjuncture of the commodity market. […] If we put aside the rapid and significant increase in the amount of money (which is of major importance for the emission of paper currency), then the reason for these changes almost never pertains to the change of the amount of money in the national economy. The quantity theory, therefore, can be applied only to the paper currency circulation. […] Here the value of money is nothing but a derivative of the monetary prices of goods, for us the value of money is a reflection of 119the general conjuncture of the commodity market. […] That is why we can call the theory of the value of money set forth here a conjuncture theory of the value of money, opposing it to the commodity theory of Tooke, and to the quantity theory (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 50-51).

More specifically:

The change in the general level of monetary prices accompanying the movement of the industrial cycle reflects the general state of the industrial conjuncture. In other words, we must acknowledge that the value of money is directly determined by the conjuncture on the commodity market. […] The conjuncture is something which changes greatly over time. At the ascending stage of the industrial cycle the conjuncture favours the rising of commodity prices, in other words, the fall of the value of money. This is explained by the growth and at the same time by the demand in all kinds of commodities. And even though the supply grows rapidly at this stage, too, demand grows at an even faster pace. But how the demand in goods can increase in the conditions of an invariable amount of money? It is done in the following way: On the one hand, the speed of the turnover of money increases, due to which the same amount of money multiplies its purchasing power. On the other hand, there is a significant increase of credit which becomes an independent purchasing power on a par with the available money (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 48-49) 32.

There were two new analytical links between business conditions (conjuncture) and the value of money (be it metallic, backed or unbacked paper currency). The first link was not original, it was developed before Tugan by J. Lescure33. It was about the mediating role of the different types of income (wages, annuities, profit, rent, etc.). The second link was new and was related to the introduction of the money demand function, endogenous in nature which brought behavioural elements in determining the impact of money on prices. For example, while only 120circulating money was taken into account by the quantity theory, for Tooke the accumulated, saved money was also important. The demand in money made it possible for Tugan to overcome the limitations of T. Tooke, who according to Tugan « denied any independent factors for the value of money that could be found on the part of money » (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 9).

The demand for money in Tugan was developed in detail and practically overlapped with the model of Keynes as regards its main components developed later in the Treatise on Money. (I disagree with I. Koropeckyj that Tugan’s analysis of the demand for money was superficial, Koropeckyj (1991, p. 75)). Similarly to Keynes, Tugan distinguished between three motives of money demand, which influenced the value of money to motive (i) related to the demand in commodities, transactions, (ii) to portfolio motive under the influence of the interest rate34, and (iii) to psychological motive, related to « public awareness, confidence », expectations about the future state of the value of money etc. Tugan examined in details these three cases initially formulating them as follows:

The amount of money in the country can affect in three ways monetary prices: (1) monetary prices may change due to changes in the amount of money under the influence of changes in public demand in commodities; (2) monetary prices may change due to changes in the amount of money under the influence of the discount rate; (3) monetary prices may change in relation to changes in the amount of money through public awareness, confidence – commodity prices in this case change due to the change in the appreciation of the value of money itself35 (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 29).

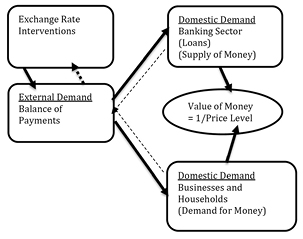

We could present simplifying Tugan’s money demand function as:

(1)

(1)

where, md is the money demand, yd is the aggregate demand (Tugan differentiates between domestic and external demand, the latter being the more important one), i is the discount rate and  is the expected value level of value of money i.e. the reciprocal of the expected price level (see Chart 1).

is the expected value level of value of money i.e. the reciprocal of the expected price level (see Chart 1).

According to Tugan the quantity theory was valid only in the regime of non-backed paper currency36. Fundamentally concerning « the unconscious, spontaneous » formation of the value of money, Tugan was in many ways close to the insights of G. Simmel, although he did not acknowledge it. Knapp’s influence on Tugan is also crucial (in my opinion it is also determined by the fact that Tugan is largely follows Nikolskiy, perhaps the most prominent follower of Knapp in Russia). However, Tugan believes that Knapp’s theory can be further developed:

Knapp’s famous book Staatliche Theorie des Geldes, is an age in the doctrine of money. […] Paper currency must be recognized as money in the full sense of the word, i.e. an independent measure of value, no less than metal currency. However, for all its great significance, Knapp’s book does not provide a definite theory for the value of paper currency (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 74).

Since Tugan knew, appreciated and criticised Marx, it can be presumed that his approach was also an original reaction within the frameworks of Marxism concerning paper currency. Subsequently R. Luxemburg, R. Hilferding, I. Rubin, made an original monetary reconstruction of the Marxist theory where money was interpreted as leading and fundamental category derived from commodity exchange37 (Orléan, 2011). Having formulated his business cycle theory Tugan’s next step was to find out the specific, and concrete variable which could influence the value of money in the regime of paper currency. That variable according to Tugan was the exchange rate.

II.2. The Value of Paper Currency,

the Agio and the Exchange Rate

According to Tugan the role of the exchange rate could be understood by comparing the value of paper currency in two (or more) open national economies (countries). The relationship between the national paper currencies was determined by the dynamics of the balances of payments. In order to see things more accurately, it was important to 122reject the opinion, according to which the agio38 (deviation of the market price of paper currency from the officially announced price, i.e. in metal) was a function of the quantity of currency39. Tugan considered that a theory should be developed where the agio was nothing but a function of the exchange rate (also referred to as veksel rate) in the regime of backed paper currency. The exchange rate is derived from the balance of payments, but there is also the feedback that would underlie Tugan’s understanding that the exchange rate could be the main anchor of monetary policy. Tugan formulated a number of postulates which underlay the « monetary approach to the balance of payments » (i.e. a correlation between the monetary sector and the external one).

It is absolutely necessary to acknowledge that the agio is in itself not the price of the paper currency in metal but the price of the foreign currency in paper […] In normal conditions of paper currency circulation the agio is for nothing else but an original manifestation of the exchange (veksel) rate, and the agio does not exist outside the exchange (veksel) rate […] Therefore the distinction which is often made between the exchange (veksel) rate and the agio is wrong […] The normal agio appears in international exchange, in the buying and selling of foreign policies (veksels) rather than in the sale of the goods themselves. […] The amount of money and the balance of payments – represent the same chain of interrelated phenomena: the amount of money determines the balance of payments, and the balance of payments determines the agio (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 77-79, p. 125, p. 128).

Tugan considered that the agio (and the exchange rate respectively) were very important for managing the balance of payments:

The agio has an important economic function: by stimulating exports and holding back imports the agio makes it possible for the country to pay its debts to the other countries by commodities. (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 127).

How to overcame the agio was the focus of discussions about monetary reforms at that time (because it was a matter of paper currency regime with a metallic backing). Tugan devoted dozens of pages of his book, focusing on the monetary history of Austria and Russia, the countries 123with a long history of paper currency. He made a detailed empirical analysis of the value of the paper currency in Austria (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 57-65)40 and in Russia (p. 89-138). Tugan devoted particular attention to the periodization of the evolution of Russian paper currency, pointing out the reasons for the emergence of an individual (independent of the metal) value of paper currency. The dynamics of the agio reflected those processes. Over time its value was increasingly determined by the currency exchange rate. Tugan distinguished between two types of agio in the regime of paper currency – (i) normal, external agio – depending on the exchange rate and external payment relations and (ii) internal agio – related to the metal when there were unexpected circumstances, – a total lack of confidence in the national paper currency, etc. (Tugan Baranovsky, 1917a p. 80-82).

In the case of Russia Tugan distinguished between two main periods and several sub-periods covering the evolution of the assignats and the credit rouble. The first was the one of the assignats (1769-1839) when paper currency had no legal validity and circulated jointly with metallic money. The second period was that of the credit roubles (1839-1897) when paper currency had a complete legal form and became emancipated from metallic money. The end of the paper currency came in 1897 with the introduction of the gold standard41. While in the period of the 124assignats, paper currency existed alongside metallic money and at first it was not even a legal means of payment, with the credit money – it became emancipated and gained an independent value. An evidence to this effect were also the lower and more stable levels of the agio in the period of the credit roubles. However:

If we compare the changes of the agio in the age of the assignats and in the age of the credit notes we shall see the following fundamental difference: in the age of assignats, the agio stood much higher than in the age of credit money. […] This fundamental difference of the two types of paper currency is completely understandable: the assignats were not really money, while credit notes were money within the entire volume of monetary functions (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 131).

Having determined the exchange rate as a key variable42 in the regime of decreed paper currency Tugan set forth his proposal for a new monetary regime to be introduced in Russia after the end of the war.

III. Non-convertible Paper Currency

and Active monetary policy

The new regime of paper currency after the war did not step on a completely unknown territory. According to Tugan (and not only, M. Bernatzky for instance), the Russian reform should draw ideas from the experience of the Austrian reform of the late 19th century (1892 – 1899-1911) which introduced active regulation of the exchange rate through interventions on the foreign exchange market. It was about 125giving a « priority to discretion instead of to the rules » in stabilising the value of the national paper currency. In Tugan’s words that could be accomplished as follows:

The Austrian monetary reform of 1892 along with the ensuing initiatives in the sphere of monetary policy represent an epoch in the history of money circulation […] The new Statutes of the Austro-Hungarian bank includes a completely new task – a regulation of the rate of paper currency at a level as close as possible to the parity. (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 141-143).

It is absolutely possible to gain stable currency without restoring exchange (NN: to metal). To this end, it is necessary to establish institutions similar to those existing in Austria. (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917b, p. 165).

The achievement of stability of the currency exchange rate should become one of the most important tasks of the future monetary reform. […] Therefore it is necessary to establish institutions like those in Austria (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917b, p. 157, p. 165) 43.

Elsewhere Tugan declared the following as regards the characteristics of the future monetary system and the place of gold in it:

The experience of recent decades has shown that apart from a system of paper currency with an unstable value, a system of paper currency with a stable value is also possible. […] One can be a convinced adversary of the old-style paper currency and defend the system of currency circulation like the one in Austria up to the current war. In any case even if it is bad this system has been imposed by the irreversible processes […] The task of active monetary policy pertains to eliminating the fluctuations, and to imparting stability to the vekselrate (exchange rate). […] The outcome of the war can create a new monetary system – a system of paper currency with a stable value. Formally this money as well as all paper currency will be secured by metal, but that collateral will be only an empty form without any economic content until that currency starts to be exchanged for metal. And what will happen to gold? What role will it play within the frameworks of the new monetary system? A large part of it will be stored in the vaults of the national central banks. […] The active currency policy must now be recognized as one of the most important constituent parts of any adequate economic programme. The movement of the veksel rate (exchange rate) should not be exposed to a 126random stock exchange influence but should be placed under the control of the state. […] The task of the active currency policy consists in eliminating the fluctuations and in imparting stability to the veksel rate (currency exchange rate) (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917b, p. 159, p. 164-166).

Therefore, to sum it up the overall Tugan’s model can be illustrated in Chart 1.

Source: Author’s elaboration

Tugan is not the only one, M. Bernatzky (1876-1943) also considered that the war and paper currency changed deeply the monetary regime44. He analysed the limits within which imposed paper currency could 127reflect the value of money and particularly emphasized the role of the balance of payments and the exchange rate. Bernatzky offered a policy of managing the volume of paper currency through the issue of domestic debt45. According to him:

It was only recently in connection with the brilliant experience of Austria-Hungary, that the view has spread that life is also possible with paper currency if it is properly regulated but for the successful regulation the abuse of issuing paper, its extraordinarily large amount in the turnover is unacceptable. […] What is the danger of unbalanced paper currency? It is a matter of such money circulation, when the measure of value is the non-convertible paper currency with an imposed rate and continuously increasing amount regardless of the market needs. In itself, exchangeable paper currency emitted on a limited scale is not harmful for the national economy and it may even provide for its tangible benefits. […] We can imagine the ideal order in the following way. When the emission of paper currency appears to be sufficient for the turnover and there are clear signs of its surplus, efforts should be made through loans to withdraw large sums from the turnover and to submit them to the government to spend them; when that expenditure is made and the currency apparatus becomes again full of redundant paper, a new loan should be granted, etc. (Bernatzky, 1917, p. 83, p. 88-89, p. 97).

Concretely, according to Tugan, the post-war reform in Russia had two interrelated tasks: (i) to restore and (ii) to stabilize the value of Russian paper currency. The first necessitated the withdrawal of a certain amount of money. Tugan calculated the necessary money supply in Russia at 4-5 billion roubles. The second objective is to maintain a parity exchange rate through intervention46. The exchange rate had to be stable in order to attract foreign capital and to get an external loan (i.e. to influence actively the balance of payments equilibrium).

Tugan was no doubt against the appreciation and revaluation of the rouble. Those views of his were formed back at the time of the reform of Witte (then during the disputes on the reform in the Free Economic Society the young Tugan supported a depreciated rate and silver monometallism (IFES, 1896).

128The stability of the rate was also important. Tugan approximated it with standard deviation (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 165). In that Tugan was a precursor of the ideas of A. Aftalion, as well as of today’s models of the exchange rate volatility (Nenovsky, 2006). Currency interventions had to be implemented for a definite part of the currency reserves fixed legally in advance (Tugan-Baranovsky, 2015, p. 166)47. Moreover, gold reserves remained in central bank vaults so as to serve as a collateral for external payments and for interventions. It is noteworthy that in his Memoirs Finance Minister P. Bark described in detail the negotiations with the Ministers of Finance of England and France in Paris in 1915, when he proposed to the allies to mobilize with joint efforts the currency reserves in a joint pool and to commit to maintaining the currency rate of the rouble on the international markets (Bark, 2017; Barnett, 2001, 2005). According to Bark the exchange rate control was an extremely important policy tool.

Concluding Reflexions

In conclusion as a comparison, I must point out the following:

First, the Great War caused an extremely strong perturbation in Russia’s monetary regime, paper currency became the major source of financing the war. The period of the gold standard existence (1897-1914) proved to be a short-term deviation from the long trend of Russian currency related to the presence of paper and unbacked money. Unlike the war monetary reality, the ideas of the metallic standard continued to dominate among Russian scholar’s economists and the paper currency was considered as a temporary deviation from the norm, as pathology. After the introduction of the gold standard, the number of economists who believed that the Russian currency was specific sharply decreased.

The years of war (until 1917) did not change significantly the positions of Russian theoreticians – most of whom believed that a return to 129convertibility was needed. Later, after the Bolshevik Revolution things certainly changed but by 1917 the supporters of the metallic standard were a majority. There were just a few economists with profound theoretical knowledge who considered the deep changes in the evolution of the monetary regime to be the result of the war.

Hence my second point. It is related to Tugan’s contributions. Tugan had always been critical as regards the gold standard (e.g. his positions during Witte’s reform in support of silver monometallism). Unlike other economists however (with the notable exception of Bernatzky), Tugan was the first one to develop a comprehensive theory of a post-war monetary regime. He did that in his book published back in 1917 where he set forth not only his own slender theory, but also his ideas of a political policy. Tugan’s ideas have triggered for many future analyses. In my opinion Tugan’s general approach was a continuation of the pioneer book of K. Wicksell Geldzins und Güterpreise (189848). Noteworthy is the similar statement by Wicksell two decades earlier:

But it would be quite possible to maintain a stable value of money without the use of reserves of a precious metal. Only it would be necessary for the metal to cease to serve as a standard of value (Wicksell, 1898, p. 35).

Unlike Tugan, however (who underscored the role of the exchange rate), in Wicksell the active monetary policy for regulating the price level 130(the value of money) was mainly reduced to a policy of interest rates. Nowadays Wicksell is considered to be a pioneer of « inflation targeting ».

Tugan’s institutional proposal was noteworthy because he referred to the « planned management of the value of money ». Those were views which twenty years later would become popular in Europe (Keynes was part of that process).

Up to now state power has almost never assigned itself the task to influence the value of money in a planned manner. […] Therefore, the task of the planned policy of money circulation, aimed at regulating the value of money does not include anything impossible. […] Active currency policy today must be recognised as one of the most important constituent parts of the adequate economic programme. The movement of the exchange rate (formation of the veksel rate) should not be left at the random stock exchange influence but should be placed under the control of the state (the government) (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917a, p. 51-52, p. 164).

Tugan certainly formulated a number of the tenets about the money demand and the aggregate demand which underlay the theory of the Treatise on Money by Keynes (1930), and about the leading role of the exchange rate and the expectations developed by (Aftalion, 1927) in his book Money, Prices and Exchange Rate. A future careful comparative analysis with the monetary theory of Keynes would be extremely useful. It would restore a historical justice – the pioneer place of Tugan-Baranovsky. To this effect there are two important articles by (Koropeckyj, 1991) and (Barnett, 2001).

Another interesting area in which Tugan’s ideas could be used is related to the Marxist interpretations of the value of paper currency. Those interpretations started with O. Bauer, R. Hilferding and R. Luxemburg (see the collection of Shmelev and Shern, 1929, 1923), later were developed by I. Rubin, and nowadays are elaborated within the modern interpretations of (Orléan, 2011). For all of them money was generated by the exchange and underlay the base of value49. The recent new macro monetary interpretations of the labour theory of value of K. Marx (MELT) proposed by F. Moseley (2015) fit in that discussion. For Moseley, the problem of the formation of value of « non-commodity », i.e. paper currency in Marx, remained unresolved.

131Finally, in the preface to the Italian translation of Tugan’s book (the book was not translated into other languages, except recently in Ukrainian), Augusto Graziani set forth his arguments according to which Tugan was a pioneer in the theory of endogenous money. Thus, Tugan fitted into the tradition of « the monetary theory of production » (Graziani, 1987, 2003). Although he was generally right, in my opinion Graziani did not thoroughly consider the complexity of Tugan’s model. A future study to this effect would also be interesting.

Going back to 1917 as a continuation of the war the October Revolution found the Russian monetary economy in a pre-collapse state. The Revolution led to a new even more interesting stage of the development of the monetary regime and of the monetary theory in Russia. That was mainly determined by the combination of war heritage which to a certain extent led to paper and decreed money with a new fundamental factor at hand – the ideology of Marxism. According to it there was no place for the market, for capitalism, for money and even less for gold in the new communist society. Gold was present in the form of « public toilets » (Lenin), or in the form of the « gold shackles » of Thomas Moore.

Paradoxically, during the years of the NEP, 1922-1924, Lenin and the Bolsheviks were forced to stabilize the rouble on the basis of gold and convertible currency, actively using the experience of the Austrian reform of 1892. Tugan’s book and his ideas were not mentioned and they were forgotten for a long time.

132Bibliography

Cyrillic (in Russian and Ukrainian, with translation)

Bark, Pyotr [1955-1966], Memoirs of the last Minister of Finance of the Russian Empire, 1914-1917, Moscow, Kuchkovo Pole Publishing House, [2017]; [Барк, Петр[1955-1966], Воспоминания последнего министра финансов Российской империи, 1914-1917, Москва, изд. Кучково поле, [2017] (in Russian).

Barnett, Vincent [2005], Discussion on the Political and Economic Role of Russia’s Gold and Foreign Exchange Reserves during the First World War(J. M. Keynes and M. I. Tugan Baranovsky), Bulletin of St. Petersburg University, 5(4); [Барнетт, Винсент[2005], Дискуссия о политической и экономической роли золотовалютных резервов России в годы Первой мировой войны (Дж. М. Кейнс и М. И. Туган Барановский), Вестник Санкт Петербургского Университета, 5 (4)] (in Russian).

Bernatzky, Miкhail [before 1917a], Russian State Bank, as an Issue Institution, Lectures in the St. Petersburg Polytechnical Institute, Ms., Moscow, National Library; [Бернацкий, Михаил[19--a], Русский государственный банк, как учреждение эмиссионное, КурсЛекций, читанных в СПБ. Полит. Институте] (in Russian).

Bernatzky, Mikhail [before 1917b], Summary of Lectures on Money Circulation, Lecture notes in St. Petersburg Printing House (éd), Ms., Moscow, National Library; [Бернацкий, Михаил [19--b], Конспект лекций по денежному обращению, издание студ. Касс, взаимопомощиприСПБ. ПолитехническомИнституте, Санкт-Петербург, типографияТрофимова] (in Russian).

Bernatzky, Mikhail [1917], « Monetary circulation and loans » in Tugan Baranovsky, M. (éd) [1917], War loans, p. 81-101, Petrograd, Printing House Pravda; [Бернацкий, Михаил[1917], « Денежноеобращениеи займы », вТуган Барановский, М., (под ред) [1917], Военные займы, сборник статей, Петроград, типография Правда, c. 81-101] (in Russian).

Blioch, Ivan [1898], Future War in Technical, Economic and Political Terms, St. Petersburg, Typography I. A. Efron; [Блиох Иван[1898], Будущая война в техническом, экономическоми политическом отношениях, С-Петербург, Типографія И. А. Ефрона,] (in Russian).

Bogolepov, Mikhail [1914], War, Finance and National Economy, Petrograd, Ministry of Finance; [Боголепов, Михаил [1914], Война, финансы и народное хозяйство, Петроград, изд. Министерства финансов] (in Russian).

133Bogolepov, Mikhail [1922], Paper Money, Moscow, Cooperative Partnership; [Боголепов, Михаил[1922], Бумажные деньги, Москва, изд. Кооперативное товарищество] (in Russian).

Bogolepov, Mikhail [1924], « State Budget and Its Prospects », in STEIN, V. (еd) [1924], Finance and Money Circulation in Modern Russia, Leningrad – Moscow, p. 3-24; [Боголепов, Михаил [1924], « Государственный бюджет и его перспективы », в: Штейн, В., (под ред.)[1924], Финансы иденежноеобращение в современнойРоссии, с. 3-24, изд. « Петроград », Ленинград – Москва] (in Russian).

Bugrov, Alexander [2017], « Great War Money: Russian Experience (1915-1917) », Dengi and Credit, No 7, p. 74-80; [Бугров Александр[2017], « Деньги Великой войны: российский опыт (1915-1917) », Деньги и кредит, No 7 c.74-80] (in Russian).

Dimitriev-Mamonov, Vasily & Evzlin Zakhar (dir.) [1915], Money, Petrograd, M. Pivovarsky and C. Printing House; [Димитриев-Мамонов, Василий & ЕвзлинЗахар[1915], Деньги, изд. Пивоварского и Ц. Типография Моховая, Петроградъ] (in Russian).

Falkner, Semyon [1919], “Monetary emission as a financial system”, in: The Problem of the Theory and Practice of Issue Economy, Moscow, Economic life Printing House, p. 35-43 ; [Фалькнер, Семен[1919], Эмиссия, как финансовая система, в: Фалькнер, С. [1924], Проблема теории и практики эмиссионного хозяйства. Изд. Экономическая жизнь, Москва, сс. 35-43] (in Russian).

Fisk, Harvey Edward. [1925-1924], Inter-union Debts. Study on Public Finances for the War and Post-war Years, Moscow, Financial Publishing House of the NKF USSR; [Фиск, Харви Эдвард[1925-1924], Междусоюзнические долги. Исследование о государственных финансах за военные и послевоенные годы, Фин. изд-во НКФСССР, Москва].

Goldman, Vilhelm [1866], Russian Paper Money. Financial and Historical Essay. With Special Attention to the Current Financial Difficulties in Russia, Moscow (ed.) URSS Publishing House, 2015; [Голдман, Вильхельм[1866], Русские бумажные деньги. Финансово-исторический очерк. С обращением особенного внимания на настоящее финансовое затруднение России, Москва, URSS, 2015] (in Russian).

Guryev, Alexander [1903], Monetary Circulation in Russia in the xix Century. Historical Essay, Moscow, URSS Publishing House, 2015; [Гурьев Александр[1903], Денежное обращение в России в XIX столетии. Исторический очерк, Москва, URSS, 2015] (in Russian).

IFES [1896], The Monetary Reform in Russia. Reports and Debates in the III Branch of the Imperial Free Economic Society, Verbatim Report, St.-Petersburg, 134Printing House Demakov [ИВЭО[1896], Реформа денежного обращения въ России. Доклады и прения в III отделении Императорского Вольного Экономического Общества, Стенографический отчет (1896). С.- Петербург, Тип. Демакова] (in Russian).

Kaufman, Hilarion [1888], Credit Notes, Their Decline and Recovery, St. Petersburg, Publishing House of the Sankt-Petersburg State University; [Кауфман, Иларион[1888], Кредитные билеты, их упадок и восстановление, Санкт Петербург] (in Russian).

Kaufman, Hilarion [1909], From the history of paper money in Russia, St.-Petersburg, Publishing House of the Sankt-Petersburg State University; [Кауфман, Иларион[1909], Из истории бумажных денег в России, Санкт Петербург] (in Russian).

Kaufman, Hilarion [1910], Silver Ruble in Russia from Its Origin to the End of xix Century, Moscow, URSS Publishing House, 2012; [Кауфман, Иларион[1910]). Серебряный рубль в России от его возникновения до конца XIX века, Москва, URSS, 2012] (in Russian).

Khodyakov, Mikhail [2018], The Money of the Revolution and of the Civil War, Sankt Petersburg, Publishing House of the Sankt-Petersburg State University; [ХодяковМихаил[2018], Деньги революции и гражданской войны, Санкт-Петербург, изд. Санкт-Петербургского Государственного Университета] (in Russian).

Kronrod, Jacob [1954], Money in the Socialist Society (Essays of Theory), Moscow, Gosfinizdat; [Кронрод, Якоб[1954], Деньги в социалистическом обществе (очерки теории), Москва, Госфиниздат] (in Russian).

Kuchin, Sergey [2006], The theory of monetary circulation in the heritage of M.I.Tugan-Baranovsky, Kyiv, Ph.D. Dissertation; [Кучин Сергей[2006], Теорія грошового обігу у спадщині М.І. Туган-Барановського, Диссертация, Kyiv (in Ukrainian).

Lomeyer, A. (ed.) [1918], Money Circulation Issues, Petrograd, éd., the Central People’s and Industrial Committee; [Ломейер, A. [1918] (под ред.) Вопросы денежного обращения, Петроградъ, изд. Центральный народно-промышленный комитет] (in Russian).

Lopukh, Kseniia [2014], « M. I. Tugan-Baranovsky’s Groundbreaking Ideas in the Development of the Theory of Money », Ukrainian Socium, 51(4), p. 122-129; [Лопух, Ксения[2014], « Новаторські ідеї М.І.Туган-Барановського у розвитку теорії грошей », Український соціум, 51(4), c. 122-129] (in Ukrainian).

Migulin, Pyotr [1904], A Note on Russia’s Financial Preparedness for War, Kharkov, Pechatnoe delo printing house; [Мигулин, Петр[1904], Записка о финансвой готовности России к войне, Харьков, тип. Печатное дело] (in Russian).

135Migulin, Pyotr [1905], War and Our Finances, Pechatnoe delo printing house, Kharkov; [Мигулин, Петр[1905], Война и наши финансы, Харьков, тип. Печатное дело] (in Russian).

Mikhailov, I. [1916], The War and Our Money Circulation. Facts and figures, Petrograd, éd., Pravda; [Михайлов И. [1916], Война и наше денежное обращение. Факты и цифры, Петгроградъ, тип., Правда,] (in Russian).

MF, Ministry of Finance, Special Chancellery for Credit [1915], Issue of Treasury Banknotes, Russian State Library, document A 318/240 [МФ[1915]. Министерство Финансов, Особенная канцелярия по кредитной части: О выпуске казначейских денежных знаках, Российская государственная библиотека, документА 318/240] (in Russian).

Mukoseev, V. [1917], « Russian Military Loans », in Tugan Baranovsky, M.I., edited [1917]. Military loans, collection of articles, p. 142-194, Petrograd, Printing House Pravda [Мукосеев, В. [1917]. Военные займы России, в: Туган Барановский, М. И., под ред., [1917]. Военные займы, сборник статей, с. 142-194, типография Правда, Петроград]

Nikolskiy, Peter [1892], Paper Money in Russia, Kazan, Imperial University Printing House; [Никольский, Петр[1892], Бумажные деньги в Росии, Казань, ТипографияИмператорскогоуниверситета] (in Russian).

Orlik, Svetlana [2017], « Problems of Russia’s Financial Policy during the First World War in the Scientific Heritage of M. I. Tugan-Baranovsky », Ukrainian History Journal, No 1, p. 60-72 ; [Орлик, Светлана[2017], « Проблеми фінансової політики Російської імперії в роки Первої світової війни в науковій спадщині М. І. Тугана-Барановського », Український історичний журнал, No 1, c. 60-72] (in Ukrainian).

Prokopovich, Sergey [1917], War and National Economy, Moscow, Typolytography I. Efimov, N. Zheludkova & B. Yakimanka; [Прокопович Сергей[1917], Война и нородное хозяство, Москва, типолитографияТ.Д. И.Ефимов, Н. Желудкова и Б. Якиманка] (in Russian).

Radetzky, Fedor [1923], What are Banknotes? Moscow, Financial and Economic Bureau of the NKF; [Радецкий, Федор[1923], Что такое банкноты?, Москва, Финансово-экономическое бюро НКФ] (in Russian).

Rykachev, Andrei [1910], Money and Monetary Power. Experience of Theoretical Interpretation and Justification of Capitalism, St. Petersburg, éd., M. Stasulevich, part I « Money »; [Рыкачев, Андрей[1910], Деньги и денежная власть. Опыт теоретическаго истолкованiя и оправданiякапитализма (часть первая. Деньги), С.-Петербург, тип. М. Стасюлевича] (in Russian).

Sharapov (Talitsky), Sergey [1895], Paper Rouble (Its Theory and Practice), St.-Petersburg, Public Benefit Printing House; [Шарапов (Талицкий), Сергей[1895], Бумажный рубль (его теория и практика), С-Петербург, типография « Общественная польза »] (in Russian).

136Shmelev, K & Shern, A (Eds.) [1929, 1923], Money and Money Circulation in Coverage of Marxism. Collected Articles by O. Bauer, N. Bukharin, E. Varga, R. Gilferding, K. Kautsky, N. Lenin, R. Luxembourg, etc., Moscow, State Publishing House of the USSR; [Шмелев, К & Шерн, А, (под. ред.) [1929, 1923], Деньги и денежное обращение в освещении марксизма.Сборник статьей О. Бауэра, Н. Бухарина, Е. Варги, Р. Гильфердинга, К. Каутского, Н. Ленина, Р. Люксембург и др., Москва, Государственное издательство СоюзаССР] (in Russian).

Shor, A & Elkin, B [1912], « Export of Grain Projects from Germany », in Tugan Baranovsky, M. (Ed.) [1912], St. Petersburg, Printing House Ministry of Finance publications; [Шор, А., Б. Елкин[1912], в Туган Барановский, М., под ред., (1912). Вывоз зерновых проектов из Германии, Типография период. С.-Петербург, Изданий Министерства Финансов] (in Russian).

Sidorov, Arkady [1960], The Financial Situation in Russia during the First World War, Moscow, éd. by the Academy of Sciences of the USSR; [Сидоров Аркадий[1960],Финансовое положение России в годы первой мировой войны, Москва]изд. Академии наук СССР] (in Russian).

Silin, N. [1917], Depreciation of Currency, Petrograd, Synodal Printing House [Силин, Н. [1917], Обезцененiеденегъ, Петроградъм Синодальная Типография] (in Russian).

Sorvina, Galina [2005], Mikhail Ivanovich Tugan-Baranovsky. The First Russian Economist of World Renown. On the 140th Anniversary of His Birth, Moscow, éd., Russkaya Panorama; [Сорвина, Галина[2005], Михаил Иванович Туган-Барановский. Первый российский экономист с мировымименем. К 140-летию со дня рождения, Москва, изд. Русская Панорама, (in Russian).

Stein, V. (Ed.) [1924], Finance and money circulation in modern Russia, Leningrad-Moscow Printing House; [Штеин, В., под ред. [1924], Финансы и денежное обращение в современной России, изд. «Петроград», Ленинград – Москва] (in Russian).

Tugan-Baranovsky, Djuci [2015], Tugan Baranovsky Mikhail Ivanovich: Life and Ideas, Volgograd, Publisher Printing House; [Туган Барановский, Джучи[2015], Туган Барановский Михаил Иванович: жизнь и идеи, Волгоград, Издатель] (in Russian).

Tugan-Baranovsky, Mikhail [1914a], New Ideas in Economics, St.-Petersburg, Education Publishing House; [Туган Барановский Михаил[1914a], Новые идеи в экономике, Издательство «Образование», С.-Петербург] (in Russian).

Tugan-Baranovsky, Mikhail [1914b], War and National Economy, What Does Russia Expect from the War, St. Petersburg, New Ideas in Economics; [Туган 137Барановский Михаил (подред.) [1914a], Война и народное хозяйство, Чего ждет Россия от войны, Новые идеи в экономике, С.-Петербург] (in Russian).

Tugan-Baranovsky, Mikhail [1915], Problems of the World War I, Petrograd, Pravda Printing House; [Туган Барановский Михаил[1915], Вопросы мировой войны, Петроград, изд Право] (in Russian).

Tugan-Baranovsky, Mikhail [1917a], Paper Currency and Metal, Petrograd, Pravda Printing House; [Туган Барановский Михаил[1917a], Бумажныя деньги и металлъ, Петроград, типография Правда] (in Russian).

Tugan-Baranovsky, Mikhail [1917b] (Ed.), War Loans, Collection of Articles, Petrograd, Pravda Printing House; [Туган Барановский Михаил[1917b], (под ред.) Военные займы, Петроград, сборник статей, типография Правда] (in Russian).

Tugan-Baranovsky, Mikhail [1917c], « Preface by Professor M. I. Tugan-Baranovsky », in Ishkhanyan, B. [1917], Development of Militarism and Imperialism in Germany. Historical and Economic Research, Petrograd, Book Publishing House; [Туган Барановский Михаил[1917c], Предисловие профессора М. И. Туган-Барановского, в: Ишханян, Б [1917], Развитие милитаризма и империализма в Германии, Петроград, Историко-экономическое изследование, Книгозидательство Книга] (in Russian).

Yurovsky, Leonid (Ed.) [1926], Our Monetary Circulation. Collection of Materials on the History of Money Circulation in 1914-1925, Moscow, Financial Publishing House of the NKF USSR; [Юровский, Леонид. (под ред.) [1926], Наше денежное обращение. Сборник материалов по истории денежного обращения в 1914-1925 г.,Москва, Финансовое издательство НКФСССР,] (in Russian).

Vlasenko, Vasily [1949], Monetary Reform in Russia 1895-1898, Kiev, Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences USSR; [Власенко, Василий[1949], Денежная реформа в России 1895-1898, Киев, изд. Академии наукУССР] (in Russian).

Yasnopolsky, Leonid [1927], TheRestoration Process in Our Monetary Circulation and Monetary Policy Tasks, Financial Publishing House of the NKF USSR; [Яснопольский, Леонид [1927], Восстановительный процесс в нашем денежном обращение и задачи валютной политики, Фин. Изд. НКФ СССР] (in Russian).

Zlupko, Stepan [1998], « The Theory of Money of M. I. Tugan-Baranovsky and Its Impact on Monetarism of the 20th Century », Ukrainian Finances, No 8, p. 99-114. [Злупко, Степан. [1998], « Теорія грошейМ. І. Туган-Барановського та її вплив на монетаризмХХ », Фінанси України, No 8, c. 99-114] (in Ukrainian).

138In Latin

Aftalion, Albert [1927], Monnaie, prix et change. Expériences récentes et théories, Paris, Sirey.

Allisson, François [2011], « Tugan-Baranovsky’s Economic Crises » in Brockhaus-Efron (1895, 1909, 1915) in Besomi, Daniele [2011], Crises and Cycles in Economic Doctrines, Abingdon, Routledge, p. 343-360.

Allisson, François [2015], Value and Prices in Russian Economic Thought. A Journey inside the Russian Synthesis, 1890-1920, London, Routledge.

Barnett, Vincent [2001], « Calling up the Reserves: Keynes, Tugan-Baranovsky and Russian War Finance », Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 53, N°1, p. 151-169.

Bogolepov, Mikhail [1931], « The Financial System of Pre-War Russia », in Sokolnikov Grigori & Associates, Soviet Policy in Public Finance (1917-1928), Stanford, California, Stanford University Press, [1931], p. 1-73.

Chaloupek, Günther [2003], « Carl’s Menger Contributions to the Austrian Currency Reform Debate (1892) and his Theory of Money », 7th Annual ESHET Conference, Paris.

Chaloupek, Günther [2019], « Positions of the Austrian School on Currency Policy in the Last Decades of the Habsburg Monarchy (1892-1914) », Annual Conference of the HES, New York, June 20 to 22.

Graziani, Augusto [1987], « La teoria della moneta di M. I. Tugan-Baranovskij », in Tugan-Baranovski, Cartamoneta e metallo, a cura di Graziani Augusto & Graziozi, Andrea, p. xv-xxiv, Napoli, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane.

Graziani, Augusto [2003], The Monetary Theory of Production, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Graziozi, Andrea [1987], « La Russia e le scienze sociali » in Tugan-Baranovsky, Mihail, Cartamoneta e metallo, a cura di Graziani, Augusto & Graziozi, Andrea, p. xxv-lvi, Napoli, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane.

Hansen, Alvin [1964], Business Cycles and National Income, (expanded edition), New York, W. W. Norton & co.

Hawtrey, Ralph [1919], Currency and Credit, London-New York, Longmans-Green & Co.

Jeze, Gaston [1915], Les finances de guerre de l’Angleterre, Paris, M. Giard & E. Brière.

Jèze, Gaston [1917], Les finances de guerre de la France, Paris, M. Giard & E. Brière.

Keynes, John Maynard [1923], A Tract on Monetary Reform, London, Macmillan.

Keynes, John Maynard [1930], A Treatise on Money, London, Macmillan, 2 vol.

Koropeckyj, Ivan [1991], « The Contribution of Mykhailo Tugan-Baranovsky to Monetary Economics », History of Political Economy, vol. 23, N°1, p. 61-78.

139Kramer, Andreas [2017], The Gold Standard in Austria-Hungary, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Working Paper, https://www.thluebeck.de/fileadmin/media/AustrianEconomics2017/pdf/kramer_andreas-the_gold_standard-in_austria_hungary.pdf (consulté le 01/07/2020)

McKay, John [1970], Pioneers for Profit. Foreign Entrepreneurship and Russian Industrialization, 1885-1913, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press.

Moseley, Fred [2015], Money and Totality: A Macro-Monetary Interpretation of Marx’s Logic in Capital and the end of the « Transformation Problem », Brill, Leiden, and Boston.

Nenovsky, Nikolay [2005], Exchange Rate Inflation: France and Bulgaria in the Interwar Period. The Contribution of Albert Aftalion (1874-1956), Sofia, Edition of Bulgarian National Bank.

Nenovsky, Nikolay [2009], « Place of Labour and Labour Theory in Tugan Baranovsky’s Theoretical System », The Kyoto Economic Review, vol. 78, No 1, p. 53-77.

Nenovsky, Nikolay [2019a], « Money as a Coordinating Device of a Commodity Economy: Old and New, Russian and French Readings of Marx, Part 1 Monetary theory of value », Revue de la régulation, vol. 26, N°2, 20 p.

Nenovsky, Nikolay [2019b], « Money as a Coordinating Device of a Commodity Economy: Old and new, Russian and French readings of Marx, Part 2 The theory of money without the theory of value », Revue de la régulation, vol. 26, N°2, 30 p.

Orléan, André [2011], L’Empire de la valeur. Refonder l’économie, Paris, Seuil.

Tugan-Baranovskij, Michail [1917-1919], Cartamoneta e metallo, a cura di Graziani, Augusto & Graziosi, Andrea, Napoli, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 1987.

Uhr, Carl [1960], Economic Doctrine of Knut Wicksell, Berkeley, University of California Press.

Von Laue, Theodore [1963], Sergei Witte and the Industrialization of Russia, New York, Atheneum, 1969.

Wicksell, Knut [1898], Interest and Prices (Geldzins und Güterpreise). A Study of the Causes Regulating the Value of Money, London, Macmillan, 1936.

1 « Literature on the world war is extensive but undoubtedly it is still in the bud: events of such an exceptional, unprecedented importance for the history of mankind as well as other events to which we do not attach such importance will attract human thought many years and many decades to come » (Tugan-Baranovsky, 1917c, p. 1).

2 The abandoning of the gold standard was declared a few days after the outbreak of the war on July 27, 1914. According to Mihailov (1916, p. 8), there was evidence: the speech by the former Minister of Finance V. Kokovtsev that the decree for terminating exchange was legally prepared back at the end of the Russian-Japanese war.

3 Leather money (meha) was often regarded as an alternative of coins and as an archetype of paper fiduciary money (see « leather assignats » in (Guryev, 1903, p. 3-4) and the standpoint of Falkner (1919, p. 37).

4 See the bibliography at the end including the main titles by those authors.

5 S. Sharapov (his book of 1895 as well as his speeches on the reform and the debates in IVEO, 1896, p. 47-51, p. 78-82, p. 249-251).

6 In the words of M. Bernatzky: « The Austrian monetary reform of 1892 along with the ensuing initiatives in the field of monetary policy represent an epoch in the history of money circulation » (Bernatzky, 1917, p. 141). «Recently in connection with the brilliant experience of Austria-Hungary the view has spread that life is possible with paper currency provided that it can be regulated properly » (Bernatzky, 1917, p. 83). Subsequently the Bolshevik economists (L. Yurovsky, E. Varga, etc.) as well as Russian emigrants expressed similar views during discussions about currency stabilization. Representatives of the Russian banks in Paris declared in 1922 that « the future Russian Bank of issue be obliged to guarantee stability of the Russian currency inspired by the example of the Austro-Hungarian bank » (CRBR, 1922, p. 58). As regards that reform see G. Chaloupek’s recents works (Chaloupek, 2003) and particularly (Chaloupek, 2019) and (Kramer, 2017).

7 Except in Italian in 1987, see Tugan-Baranovskij (1917-1919). It was recently translated in Ukrainian (2004). Ukrainian economists have devoted numerous studies to Tugan’s ideas of money in recent years (Zlupko, 1998; Kuchin, 2006; Lopukh, 2014; Orlik, 2017).

8 For details see Tugan’s biography written by his grandson Tugan-Baranovsky (2015) as well as Sorvina (2005).

9 Bliokh (1898); Migulin (1904, 1905).

10 See the survey by Prokopovich (1917, second edition 1918; also in French) and above all Sidorov’s book (1960). They are the best sources on the subject.

11 Those processes were described in detail in Bark (2015).

12 The articles were written in 1916, the book was submitted for print on December 2, 1916. The book was under the auspices of the All-Russian Committee for public cooperation for war debts.