Concevoir un concept d’outil numérique pour le dialogue interentreprises en utilisant une approche orientée client Le cas des services de restauration

- Type de publication : Article de revue

- Revue : European Review of Service Economics and Management Revue européenne d’économie et management des services

2020 – 1, n° 9. varia - Auteurs : Sarkkinen (Eliisa), Pöyry-Lassila (Päivi)

- Résumé : Cet article explore ce qu’est l’orientation client dans un contexte de service B2B et il rend compte d’une étude de cas empirique pour un outil numérique de relation client construit en utilisant la conception de service et la « customer-dominant logic ». La conclusion est que l’orientation client dans le contexte B2B nécessite une interaction multidirectionnelle : comprendre le monde du client et transformer ses défis et ses besoins en un système holistique. Le concept résultant forme une sphère commune pour l’orientation client en comprenant les problèmes réels du client B2B en leur trouvant des solutions.

- Pages : 17 à 52

- Revue : Revue Européenne d’Économie et Management des Services

- Thème CLIL : 3306 -- SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES -- Économie de la mondialisation et du développement

- EAN : 9782406106043

- ISBN : 978-2-406-10604-3

- ISSN : 2555-0284

- DOI : 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-10604-3.p.0017

- Éditeur : Classiques Garnier

- Mise en ligne : 06/05/2020

- Périodicité : Semestrielle

- Langue : Anglais

- Mots-clés : Orientation client, services interentreprises, outil numérique de relation client, conception de services, services de restauration

Designing a digital tool concept

for business-to-business dialogue

using a customer-centric approach

Case food services

Eliisa Sarkkinen1

Haaga-Helia University

of Applied Sciences (Finland)

Päivi Pöyry-Lassila

Laurea University

of Applied Sciences (Finland)

Introduction

Today’s growing competition and rapid technological change forces companies to become faster in their processes and data handling (Marvin, 2017), and adopt new development principles such as Design Thinking and Service Design, Design Agile, and Lean (Holtzblatt et al., 2014; Ries, 2011; Cooper et al., 2016). The rapid technological change has transformed into a turning point – an “era of information explosion” (Bagheri and Shaltooki, 2015, 340), “the Enlightened Age of Data” (Arthur, 2013, p. 10-11) and the “Age of Value Creation” (Cooper et al., 2016, p. 24).

To survive this transformation, companies must create value for the clients as in today’s business the power has shifted from supplier 18to customer (Cooper et al., 2016). Theoretical approaches, such as customer-dominant logic (CDL) (Heinonen and Strandvik, 2017), service-dominant logic (SDL) (Vargo and Lusch, 2008) and service logic (SL) (Grönroos, 2011) have arisen to help conceptualize the deep meaning of customer-centricity.

The motivation for this study was threefold. First, the lack of information about customer-centric solutions was identified in the B2B context (Ulaga, 2018), whereas for end-customers, or in the context of B2C, solutions e.g. online banking services, are being developed more often from the point of view of the customer. Could this be linked to the overall gap between B2C marketing literature and B2B marketing literature (Lilien, 2016)? Solutions are implemented mostly from the supplier company’s perspective, whereas customer-centricity is to a great extent neglected. At the same time, the need for customer-centric solutions is growing as the need for more efficient communication between the business client and the supplier has become even more critical (Marvin, 2017). Ulaga (2018) points out that even companies manifesting a customer-oriented mindset need customer-centric tools and methods to make it real. They need to address the issue of how to create digital solutions to support customer success in the B2B context.

Second, scientific literature is still scarce in the area of the client-oriented view related to portal or extranet solutions. Literature including content on extranets and portals (e.g. Baran and Galka, 2017; Woodburn and McDonald, 2011, Vlosky et al., 2000) is mostly related to customer relationship management systems (CRM), and emphasizes the company perspective. It seems that the current account management discussion is mostly on websites offering loads of articles, blogs, supplier offerings on developing portals and extranet. Short one-page articles in Certified Public Accountants’ publications can be found on client portals and their benefits (e.g., Higgs, 2015; Girsch-Bock, 2015).

Third, there seems to be a lack of hands-on information on customer portals and their efficient usage. It must be noted that extranet itself is not a new concept. Companies, especially global enterprises offering multiple services, have developed technological solutions to strengthen their services and customer relationships already years ago (e.g., Grönstedt, 2000; Secoya, 2017; Agasthi, 2016).

19We acknowledge the importance of service innovation (e.g. Witell et al., 2016; Carlborg et al., 2014; Barrett et al., 2015) and network theories (e.g. Barile et al., 2016) but we do not focus on them in this article, as the theories mentioned above (CDL, SDL and SL) offer a clear conceptual lens for understanding our case study. Customer-centricity has become a central topic in research and practice especially in the B2C context. However, in the B2B area, a deeper understanding is needed to close the gaps of knowledge.

To sum up, research is needed to clarify how customer-centricity can be incorporated into the B2B client relationship digital context, both in practice and theory. Digital transformation and customer-centricity affect today’s business including traditional businesses and their B2B clients, such as the food services industry and the case company as a part of it. For the case company, customer-centricity was a natural approach as some clients started to ask for a client portal which created the need to build one.

As this study focuses on customer-centricity, the clients’ ecosystem and value-in-use (Heinonen and Strandvik, 2015), clients thoughts, actions and the reasons behind them, service design approach offers a firm ground for this qualitative case study in the field of food service. The objective of this study is to find answers to the main research question: “Customer-centricity — how can it be used in building a digital business-to-business client relationship tool”. In addition, this study aims to direct a customer-centric perspective to account management in the field of food service by developing a client portal concept based on client needs. As this study involved collaboration with the case company, also developmental goals were included in the research. In this case study, the practical development objective was to find an answer to the following question “What should the portal be like including ideas, feelings, stakeholders, challenges, features, content and benefits?” The goal was to develop a client portal concept based on clients’ needs identified in the empirical research. The development objective gave a concrete and testable answer to what kind of aspects needed to be taken into account when creating a customer-centric digital tool. Further, the goal was to discover the challenges, meaningful issues and needs people face, including the perspectives of the clients and the staff of the case company. In the context of business-to-business research, we also reflect on the questions of how 20customer-centricity can be defined, and what are the best practices when building a customer-centric digital tool.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The next section presents the theoretical framework, followed by a description of the empirical case study in section 2. In section 3, the findings of the study are presented, and section 4 concludes the article and discusses the results of the case study.

1. Theoretical framework

Before going any further, it is to be reflected why digitality has become such a necessity for businesses as e.g. Baltes (2016) states. Previously, changes in businesses were mainly driven by client demand, competition, and expectations of quality. Other change drivers included, e.g., the need for organizational growth, production cost reductions, individual leadership agendas, the economy and new technologies (Bonvillian, 1997). Has digitalisation together with globalisation changed the ability to foresee and optimise these factors which used to be easier to calculate and analyse? The role of data is changing and becoming more and more important (Rogers, 2016). According to Dragland (2013), in 2013, about 90 % of the world’s data had been created in only the past two years, and according to Harris (2016) data created in 2017 was more than the amount of data created in the past 5,000 years of humanity. According to Marvin (2017), companies that are able to face and tackle the challenges linked with handling and integrating large amounts of data, will gain increased competitive advantages. Companies are becoming more and more aware of the possibilities it offers to decision making and to their own company’s deficiencies in the current systems (Bagheri and Shaltooki, 2015) and, also to the field of account management (Baran and Galka, 2017).

As one of the solutions that tackle the challenge of digitalisation, they have created extranets and client portals, to share data with direct access to relevant documents (Berkovi, 2014; Vlosky et al., 2000). Already in 1997, Greengard stated that a well-designed extranet creates 21efficiencies and monetary benefits, eases the lives of its users and adds value. Grönstedt (2000) praises how it enables faster communication, but as Higgins (2011) claims, despite its potential value, such as significant growth in return on investment (ROI), only 20 to 40 % of companies have a client portal, an extranet and those who have it, do not take full advantage of it. According to Berkovi (2014), Vlosky et al. (2000), Kepczyk (2008) and Girsch-Bock (2015), a major benefit that client portals offer is the accessibility to documents and network. Kepczyk (2008) and Girsch-Bock (2015) list the secured data access as benefits as well. Kepczyk (2008) adds that portals enhance processes, and Grönstedt (2000) points out benefits in faster communication. Large files are also easier to transfer, as Kepczyk (2008) states that sending documents by email creates a risk, as they go through several unknown servers. Another bonus is that creating a portal login link on the company website can act as a marketing opportunity (Girsch-Bock, 2015).

However, building solutions until recently has been relatively provider-centric, not taking the customer perspective into account. This is changing as customer-centricity is pushing away product-centricity, with its transaction-oriented business, and has turned business towards tailorable solutions and services, in which the focus is on customer relationship management, customer satisfaction, and retention, as well as constant solution development (Galbraith, 2011; Shah et al., 2006). In literature, customer-centricity is described as a customer-oriented approach: organising around the customer with a customer-centric mindset, as Galbraith (2006) defines it. This view is close to how Fader (2012) sees customer-centricity: defining the most valuable customers and aligning the company’s services to fit their needs. However, the questions remain: How is customer-centricity defined in different contexts? In this research, we define customer-centricity in the B2B context as enabling more intense interaction between the customer and the service provider, and all the other relevant parties. This interaction can be seen as a prerequisite for the value co-creation (Grönroos and Voima, 2013) in service business.

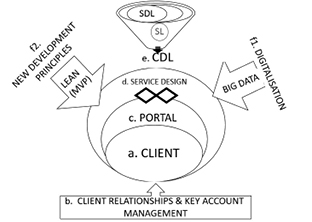

Which phenomena have influenced the transformation towards a more customer-centric business approach and the need for digital solutions? This question directed the literature review related to the research question and developmental goal. The framework presented in Figure 1 shares the 22authors’ understanding of how these theories are linked with the research questions and the developmental goal. The theoretical framework aims to create a holistic understanding of the relevant topics connected to client relationship management, such as digitalisation, service business and lean development. Also, the multidisciplinary nature of service design (Schneider and Stickdorn, 2010) supports this approach.

Fig. 1 – Theoretical framework of the case study.

The framework depicts how the client (a) is in the core of the concept creation and in the centre of the service as the client is the one defining the value-in-use (Heinonen et al., 2013; Heinonen et al., 2010) of the service. In this research, the focus is on enabling the interaction between the client and the service provider.

Further, Grönroos’ (2011) service logic adapted in client relationship (b) management underlines that it is the client who defines whether there exists a client relationship and a touchpoint with the company. The client is the one using the portal together with the account manager in the client relationship. Account management is a general definition of client relationship management. According to Payne and Frow (2005), 23account management is a core strategic function in companies focused on enhancing value by developing relationships between the company and its clients.

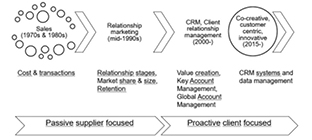

Already in 1997, McDonald, Millman and Rogers stated, that account management was more complex than it had been before. Now, more than 20 years after this statement, account management is likely to be even more complex as changes in the business environment have become more rapid. In the 1970s and 1980s account management was considered mainly as a sales functionality (Gosseling and Bauwen, 2006). Supplier needs and costs were the focus, and models such as Transaction Cost Economy (TCE) prevailed. In the mid-1990s, account management shifted towards relationship marketing (Gosseling and Bauwen, 2006). Account management had an emphasis on market share and size (Johnson and Selnes, 2014) and instead of focusing on the client needs, the theoretical discussion was more focused on the seller as a passive supplier actor (Gosselin and Bauwen, 2006). Account management theory was mainly discussed by McDonald et al. (1997) and scientific studies were scarce before the year 2000, after which a more holistic approach took over. As the theoretical background of account management is not straight forward, Figure 2 below presents the evolution of client relationship management from transactional perspective to client-focused management.

Fig. 2 – The evolution of Client Relationship Management

(Gosseling and Bauwen, 2006; Johnson and Selnes, 2014;

McDonald et. al, 1997; Millman and Wilson, 1995).

Client relationship management today requires insight of the customer’s ecosystem (Heinonen and Strandvik, 2015), which is relevant for the business in order to keep up the pace in competition, and to understand the clients’ changing needs. The client relationship should be a platform for several people and systems working together, interacting, seamlessly supporting the account manager, but instead of the account manager being the only one connected to the client, the other functions should be linked to the client (Woodburn and McDonald, 2011). Stronger connections prevent clients from leaking out of the bucket, so to say (Cheverton, 2008; Woodburn and McDonald, 2011). According to Woodburn and McDonald (2011), new web services offer possibilities of interaction and communication between the client and the provider—they get pulled towards each other’s internal environments and become more interdependent. Could data management help in reaching this interdependent stage? Could the portal connect the supplier’s and client’s core people and keep the sides attached and increase the retention rate? Therefore, in this theoretical framework (see Figure 1), portal (c) is seen as a facilitator of this interdependent relationship and interaction, so that the face-to-face communication in client relationship management can remain as the top priority. It is the platform which should be built by understanding all the surrounding influencing factors and service business theoretical points of view, always keeping the client at the core – customer-centricity and interaction with the customer in mind.

Service design (d) methods and process, the Double Diamond model (d) (Seymour, 2010), is used in developing the portal, so that it would serve the clients in the best possible way. Therefore, knowing the clients’ needs and understanding their problems is important (Schneider and Stickdorn, 2010). As Reason, Løvlie and Flu (2016) have put it, service design helps companies to react to fast-changing customer needs, to competition and to create innovative solutions, as the customer-oriented or customer-centric nature of services design can contribute to keeping the current customers, create new sales, efficiency, and reduce costs. Service design and its process is about improving an existing service or creating a new one (Kuosa and Westerlund, 2012). Mager and Sung (2011) define that service design is shaping services co-creatively to fit customer needs, an interdisciplinary strategic approach for service offering 25positioning. Service design with its customer-centric nature focuses on the customer and takes them along on the co-creative service design process. The service designer should see the company from the point of view of the customer. (Schneider and Stickdorn, 2010)

As Schneider and Stickdorn (2010) state, service design tools are explorative and intimate enough, and therefore they support the goal of discovering needs, challenges and assumed benefits of the portal. Their co-creative nature also engages people, which is needed in order to create a concept that can later be turned into a system that is really used. In addition, the interdisciplinary and inter-organisational nature of service design fits in this study, as the portal can also be seen connecting interdisciplinary knowledge from all the various experts around the company, and to build it, these experts need to be involved.

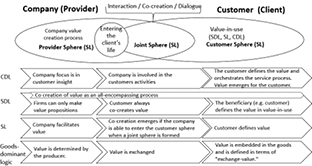

The customer-centric approach is theoretically supported (e) by the customer-dominant logic (CDL, Heinonen et al., 2010) with its strong customer-related aspect dominating the business in which the managerial mindset is transformed to seeing the customer in the centre of all decisions (Heinonen and Strandvik, 2015). Service logic (SL) (Grönroos, 2011) and service-dominant logic (SDL) (Vargo and Lusch, 2008) also have a strong influence on the customer-centric approach (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 – Service process from the value perspective in CDL, SDL, SL and GDL

(Vargo and Lusch, 2008, adaptations from Grönroos and Voima model, 2013, 141; Grönroos, 2011, 244; Heinonen et al., 2013, Heinonen and Strandvik, 2015).

One major aspect of these approaches is how value is formed and whether it is co-created, how the role of the customer and the provider is perceived in the service process, and who defines value (see Figure 3). In the traditional goods-dominant logic the provider created value, value was exchanged, and the customer was considered as a passive actor using products (Womack and Jones, 1996; Heinonen et al., 2010; Vargo and Lusch, 2008). This definition of value is contradictory to service-dominant logic (SDL), service logic (SL) and customer-dominant logic (CDL). In CDL (Heinonen and Strandvik, 2015), value is formed in the customer’s context through their own actions and feelings when they interpret, experience, and incorporate the offering in their daily lives. This forms value-in-use (Heinonen et al., 2013; Heinonen et al., 2010), and value can emerge whenever, it has an emotional side, and it can change and be reinterpreted (Heinonen et al., 2010). In SDL, according to Lusch and Vargo (2008; 2017); Heinonen et al., 2010), value is co-created during the entire service process by synergic benefits between several actors and resources in a service ecosystem where everyone related to service can be seen as an active co-creator. In service logic (SL), the customer always perceives and defines value (Grönroos, 2011), and what makes the customers’ lives “better off than before” (Grönroos, 2008, 303) is seen as the value for the customer.

In terms of the theoretical framework of this study, CDL is the main theory, but SL and SDL have an influence. The model of service logic (SL) created by Grönroos and Voima (2013), with its joint sphere in Figure 3 where the provider and the customer are connected, visualizes the connecting nature of the portal. Service-dominant logic influences with its concept of co-creation (Vargo and Lusch, 2017).

Digital transformation impacts business (Rogers, 2016) and client relationships, and therefore is a relevant issue connected to the client portal development. The arrow of digitalisation (f1) describes how this transformation is impacted by the increasing amount of data to use, the so-called Big Data (De Mauro et al., 2015). When it comes to the portal, the company can use the portal as a connector of data from several sources and use this Big Data (De Mauro et al., 2015) in creating valuable insight and possible value. It is a way to enhance interaction.

27But who defines the value of digitalisation? As digitalisation influences all layers in the ecosystem of businesses: companies, their clients, their client’s clients etc., they are all affected by its possible value and challenges. In the context of customer-centric business-to-business, it is crucial to understand that digitalisation affects both parties – the company and the client. As according to Heinonen et al. (2010) customer defines value-in-use, the value of digital tools must also be seen from the customer’s perspective. Company-centric digital tools should not be built for clients. Tools should be customer-centric and for this to be possible, one must understand how digitalisation affects customers and how their world transforms.

New development principles (f2), such as Lean Startup (Ries, 2011) and its concept of Minimum Viable Product (MVP, Ries, 2011) are connected to service design. Lean development in client portal concept creation is used in creating a minimum viable product. This way the client in the centre of the service is reached as fast as possible and feedback on the idea can be used to develop the concept further. This is a fast way to keep up with the pace of increasing digitalisation.

2. Case study implementation

This research was implemented as a single case study (Yin, 2012), with the aim to produce an in-depth analysis of the selected case. Further, to guide the reasoning process of this research we chose the contextualization strategy (Ketokivi and Mantere, 2010) that aims at inference to the best explanation, or abductive reasoning, where the processes of inference and explanation are inseparable and intertwined. Following this strategy, we aimed at ‘contextual authenticity’ in reasoning, i.e., reasoning was understood as a context-dependent process that would lead to the best possible explanation of data with regard to the cases at hand (Ketokivi and Mantere, 2010). Further, according to Eriksson and Kovalainen (2016), the idea of abduction was to dig into real life, shape that insight into categories, and by doing this, 28to create an understanding of a phenomenon. Following these ideas, this research aimed at analysing a real-life case and finding the best possible explanations in the given context, but, e.g., no statistical generalizations were pursued.

Following Ojasalo, Moilanen and Ritalahti (2014), this study was a service design case study combining elements from action research (Costello, 2003) and constructive research (Lukka, 2003). According to Ojasalo et al. (2014), this study was partly considered as an action research, as it enabled the case company’s staff to participate actively in the process by being interviewed or participate in collaborative workshops. However, it did not implement the solution, which is a prerequisite of action research. This study was also informed of constructive research (Lukka, 2003), as it tried to build a solution, the concept.

As the service design process is considered to be customer-centric with its participatory and customer-focused approach, it was chosen as the practical development goal of this study, i.e., creating a customer-centric digital business-to-business client portal concept and understanding what kind of needs the clients have, what challenges they face in their daily work, and what relief and benefits they expect to receive by using the portal. After comparing different service design processes, the Double Diamond (Davies and Wilson, 2015; Kaner et al., 2014; Schneider and Stickdorn, 2010, 126; Seymour, 2010) was chosen as it provided the best overall description of the phases of this study. According to Davies and Wilson (2015), the Double Diamond process consists of four phases: discover, define, develop and deliver. The discover phase is about gathering insight. The defining phase is making sense of the insight and narrowing it for the develop phase which is for testing and prototyping the defined ideas. The last step is to implement and deliver the developed ideas.

The case company is a major Finnish family-owned company operating in eight European countries and exporting products to approximately 40 countries. At the time this study was conducted, the case company had six business units focusing on food service, bakery, confectionery, grain products, lifestyle foods as well as café services. At that time, the company was ca. 130 years old and employed a total of 15.000 people. This study was made for the food service business unit. At that time 29the company served food in more than 600 restaurants in Finland to all customer segments: business, industry, day care centres, schools, universities, cafeterias, senior care, public institutions, and events.

The portal concept project was initiated inside the case company as a client of the company was interested in it, and also, as it was seen as a potential solution to the case company’s current business challenges. One particular challenge the case company currently faces is the amount of different IT systems the account managers use when interacting with the clients. Another challenge is the number of emails and sharing of large files with the clients. The third challenge is the expertise scattered around the organisation, and the fourth challenge is the very heterogeneous and diversified group of clients. The case company aimed to find out what kind of portal would serve them best in addressing these four challenges, and whether there were other needs beyond the client needs requiring the portal. The case company was also interested in understanding the portal’s possible benefits and most importantly creating it to match the clients’ needs.

Data was gathered in nine client, ten staff, three benchmark in-depth interviews, and in three facilitated internal staff workshops. The interviews within the organisation, the internal client interviews, were conducted in the company during June-August 2017. The client interviews lasted until October 2017, and the empirical part of the study finished in February 2018.

Altogether, eleven data collection, service design methods and tools were used in this study (Table 1), which could all be seen as supporting the customer-centric customer-dominant logic approach aiming to understand how the company’s offering connects to the customer’s world (Heinonen et al., 2013). The phases follow the Double Diamond process explained above.

30Tab. 1 – Research methods and service design tools of the case study.

|

METHODS USED IN THIS STUDY |

|||

|

PHASE |

METHOD |

APPROACH & GOAL |

INFORMANTS |

|

Discover |

In-depth Interviews: 11 staff, 9 clients |

Data source for the study |

Staff: ICT, Operations, Quality, Finance, Sales, Procurement, Digital Operations Client: Industry Business, Public Offices, Health sector, University, Real estate operator |

|

Discover |

Benchmarking interview |

Benchmark experts |

Digital Transformation Managers and a Key Account Manager |

|

Discover |

Mind map during interviews |

Understand clients’ and company’s ecosystem |

|

|

Discover |

Empathy map |

Map interview & workshop insight together |

|

|

Discover |

Internet search |

Benchmark other solutions |

|

|

Discover |

Workshop I: World Café |

Facilitation tool in a co-creative workshop |

|

|

Discover / Define |

Workshop I and II: MeWeUs Brainstorming |

Facilitation tool in a co-creative workshop |

|

|

Discover |

Workshop I: Stakeholder map |

Understand clients’ and company’s ecosystem |

|

|

Define |

Workshop II: Jobs-to-be-done canvas |

Understand the clients’ underlying motives |

|

|

Define |

Workshop II: Customer experience & business value matrix |

Prioritize features for the MVP |

|

|

Discover |

Personas |

Visualize the insight from client interviews |

|

|

Develop |

Data flow & Expressive service blueprint |

Connecting MVP features and current systems |

|

The discover phase was about gathering insight of the clients’ and case company’s current situation and of the whole topic to be dealt with. In this case study interviews (e.g. Ojasalo et al., 2014) were used to determine clients’ and staff’s needs. The most important source of customer-centric data were the client interviews representing different segments in order to include the needs from various aspects. Benchmarking interviews (Ojasalo et al., 2014) gave insight into best practices of the digital customer-centric service design projects. Interviewees represented different roles following the principles of service design according to which silent knowledge hidden in organisations is revealed by emphasizing interdisciplinary participation (Schneider and Stickdorn, 2010). Regarding internal staff, considered as internal clients, it was also important to invite them from different roles.

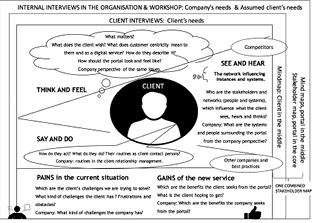

This was how the MVP was created. Following advice by Brinkmann and Kvale (2015) as well as Krippendorf and Bock (2009), all interviews were recorded, transcribed and coded by qualitative content analysis, including the final discussions in the workshops. Interviewees created mind maps (Curedale, 2013; Mahmud et al., 2011, Tuulaniemi, 2011) and workshop participants created a stakeholder map (Schneider and Stickdorn, 2010; Smaply, 2016) to understand the connections between the client, the portal and the whole ecosystem. Ideation and facilitation tool “MeWeUs” (Nummi, 2012) and world café (Brown and Isaacs, 2005; Schieffer et al., 2014) were used during the first workshop. Groups brainstormed on clients’ and company’s challenges and benefits related to the portal, as well as created the stakeholder map. In the end of the discover phase, the empathy map (Osterwalder et al., 2010; Tschimmel, 2012) was used as a framework (Figure 4) to gather and categorize all the interview and workshop insights together from quotes of what customers and staff say, think and do, how they feel about the client portal, and to whom and to what they are connected to in a customer-centric way. It visibly puts the client in the middle and helps mapping and improving the customer experience (Curedale, 2016). It visualises the portal features, functionalities, needs, challenges, benefits and stakeholders from both the clients’ and company’s side.

32

Fig. 4 –Empathy map in the client portal concept project

(modified from Osterwalder et al., 2010, @Strategyzer AG, Strategyzer.com).

The quotes from the discover phase interviews and workshops were used as sources of insight in the next workshop during the define phase. A total of 20 minutes was given for the (partly new) participants to silently read quotes related to what clients and own staff have said. Quotes described current and possible challenges, risks, benefits, feelings, concrete needs, functionalities, features and data content. After reading the quotes, participants were asked to fill in a jobs-to-be-done canvas (Ulwick, 2017; Leavy, 2017) with every row starting with one of the client’s wished feature or content. This tool revealed underlying motives and made the participants think from the customer’s perspective e.g. “By using this feature [fill in]. I want to [fill in]. So that I can (achieve a goal) [fill in].” This was followed by prioritising the features and mapping them to the customer experience business value matrix (Tuulaniemi, 2011).

Concepting emphasized the first diamond of the process and the third phase, develop, focused on understanding which of the case 33company’s current systems already contain some of the wished features and content and what was missing from the current systems. An initial data flow was created and used in the third workshop to match the wished features in the MVP with the current systems and to see possible missing systems. The last empirical phase, deliver, included creating an expressive blueprint (Kimbell, 2011) for each feature and functionality as a prototype of the concept. These blueprints were not included in this article.

3. Findings of the case study

The findings of the study are based on the empirical data collected from the interviews and workshops with the help of the various service design methods and tools used during the Double Diamond process. The findings of this study include the results from the benchmark interviews, client portal concept, personas and stakeholders of the system, and its perceived challenges and benefits. The findings will be presented in section 3.1 and discussed in section 3.2.

3.1. Findings

Benchmark interviews were used for advising how to proceed in the portal concept creation. According to the benchmark interviews, customer-centric best practices, when creating digital tools, is co-creation with the customer, constant feedback evaluation and testing as well as choosing the right methodology. They also stated these as the common pitfalls companies make. Companies believe they know what the customer wants and yet react too slowly to meet customer demands. Prerequisite for a successful project is a multi-skilled team with the right customer-centric mindset, led by a socially and technically skilled project manager and the knowledge of technical prerequisites, such as data accuracy and integrations. The interviewees advised creating a portal service first for the most valuable clients, not all. A standardised modular minimum viable product building was recommended. They 34underline that a common challenge is changing the old way of doing, but from their experience, once the project was running, it created inspiration and acted as a source of new competitive ideas. As in service design, discovering the scope of the research topic often starts by understanding the underlying needs and why should a portal exist, we start by presenting the main insight and current challenges that came up in the interviews and the first workshop.

The main thought among clients and staff inside the company was that this portal could serve as a client relationship portfolio and a forum for common dialogue. This supported our view of its role as an enabler of interaction. The clients showed a lot of interest in having the portal, and their positive attitude was apparent.

And I would love to get to see the first preliminary layout […] The elements and features. It is really great that something like this is being planned.

Let’s just say that this came just at the right time […] It would be fantastic that you would have an extranet. What is your schedule? We definitely want to try out the prototype. For long, this has been a flaw in the process […]

According to the findings, clients and the organization in the current situation share seven challenges. First is the challenge of the overwhelming number of mails and the feeling of not being able to keep track of important messages and latest documents. The second challenge is transferring knowledge to new staff members and other people, as well as saving the history data of past decisions. The third challenge is a clear communication process. There is a challenge to connect several people directly with the same message. The fourth challenge is that the client does not always know, whom to contact for a specific issue. The fifth challenge is knowing and remembering what is planned to happen in the future. An idea of an annual cycle came up. The sixth challenge, which only the clients brought up, was related to feedback. The clients want to have a system to track actions, quick access to current feedback and the trends in it. They also feel that the guest satisfaction survey done once a year is too heavy and only measures a cross-section of a moment.

Both parties also perceive three challenges related to risks in the ready portal: ensuring users’ motivation to use the portal as well as confidentiality and ease of use of the portal. Case company’s staff’s 35comments were mostly related to concept management and resources and they wish the portal not to become “yet another system”.

Client needs were derived from challenges. During the interviews, discussion of challenges led to non-functional needs, such as reliability (e.g. data security) and usability (e.g. tailorable views, need for integrations and easiness) and from there, interviewees brought up specific content and features they thought would be helpful. Here are some quotes describing the needs:

It would be really fantastic if I could receive the reports in one place already analysed and turned into graphs comparing, for example, the last month with rolling. Because that takes up a lot of my time.

That you wouldn’t have to separately save using emails because that is pretty much pointless work.

If the person changes, even if I were to dump all the emails to someone else, they couldn’t make head or tail of it.

The annual calendar is a good idea because a lot of ideas are thrown around and they are just dead ducks and then they just won’t go away.

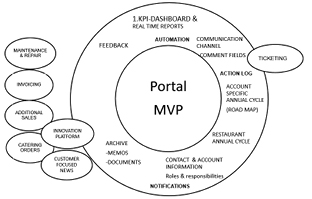

In this case study, the development goal was to develop a client portal concept based on client needs identified in the empirical research. The MVP (Figure 5) was a part of the concept and was created during the second workshop based on the prioritisation of the participants’ insight gathered from the clients’ comments. The MVP below describes the main functionalities, features and content the clients wished the portal to include: archive for documents and memos, contact information with roles and responsibilities, communication dialogue functionalities (comment field, chat), annual cycles for both restaurant campaigns as well as client relationship related topics, action log functionality, KPI dashboard with real-time reports, and last, the client-specific material. Invoicing and catering orders were left out of the scope, as they had an already functioning system that could be later integrated to the client portal if wanted. Also, the maintenance-related features were not ranked high in customer experience or business benefit. Idea platform and development road map were seen as nice features, but not necessary in the beginning. News was considered to be important but not crucial. These were added to the road map.

36

Fig. 5 – Minimum viable product for the client portal concept.

Knowing the client contact persons was important in order to understand their world. Therefore, client interview insight was turned into personas revealing two main client profiles: the “Dynamic” and “Brand loyal”. The first persona, “Dynamic”, was a very dynamic career-focused person. This person was responsible for taking care of several supplier connections. She wanted efficiency, business benefits and clear communication with the provider. She might have been sometimes overwhelmed with the number of emails, but as a fluent ICT person, she fought her way out. She was used to portals and the ones she used needed to work well. She might have even participated in developing one in her own organization. She used a lot of digital services and she expected those to be offered from the supplier as well. Here is a defining quote of the persona: “I manage basically all the contracts and report to myself”.

The second persona, “Brand loyal”, took care of supplier contact as a part of her other work. The persona had a lot of other responsibilities and was a highly valued expert in the company. In most cases, the persona had been a contact person for a longer time and knew the supplier well. Mutual respect was present, and loyalty both ways was 37concrete. The connection was close to synergy: they wanted to sell the company brand and were proud of being the company’s client. They expected high quality and renewals, as they were constantly doing those themselves. This persona type had more client contracts with a management fee contract than the other persona. Here is a defining quote of the persona: “Of course we want to create more sales for you… So that I could speak for you.”

As personas deepened the understanding of the perspective of the main contact person on the client’s side, it was also important to know who else should have access to the portal. A stakeholder map was created for this purpose. According to the results, main users could be grouped into three: account managers, client contact persons and restaurant managers. Both sides had the usual company functions behind them: marketing, procurement, ICT, communications, finance, HR, etc. They send data to directors, steering committees, HR, and finance. Other key stakeholders inside the company are the portal super users and maintenance team, and in the client’s side departments such as HR, people who need frequent reporting, estate owners and e.g. key persons in the municipality sector. Partners, vendors, outsourcing, media, trends, prospects, and the political situation, might also indirectly influence the needed KPIs and reports as well as the company’s other business units.

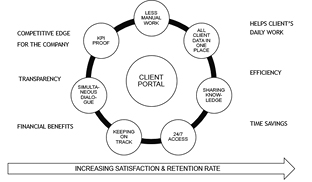

What are the benefits of a portal? According to the results, the portal, once in use, could bring various benefits (Figure 6). The benefits were categorized by grouping related quotes together and finding the common nominator. Quote “There would be a place where both parties could find up-to-date documents and the latest versions and agreements. We both could keep track of the current situation” describes one of the “Keeping on track” category quotes and “It will ease and speed up my workload tremendously” describes how the portal is seen as assisting in daily routines. The following text describes the three main benefits combining the more detailed ones presented in Figure 6.

38

Fig. 6 – Benefits of the portal system.

Benefit 1 was defined as “Everything in one place and the possibility to use the same data simultaneously”. The archive functionality would give the company and the client the possibility to see the same document, at the same time, in the same place and share it with others. The company saw these as being beneficial as well for the clients. The clients saw this would be a handy place to quickly check the current situation and have everything in a compact place.

Benefit 2 was defined as “Efficiency in many ways.” Clients and company both recognized that the portal could save time, as the number of emails, searching for the right document and archiving them would be minimised. Sharing information and having a common dialogue was seen as making things more efficient and saving time, which could be allocated when meeting clients later on. According to the client and the company, various benefits would ease the client’s daily work. The possibility to access data whenever needed would also save time, as the data would be updated directly to the dashboard instead of having to ask for the KPI reports separately. The company also saw this as a great benefit to the client. Also, the amount of manual work would be minimised, and time saved if, e.g., uploading the reports from the business intelligence system could be automated.

39Benefit 3 was defined as “Transparency and enhanced communication”. Portal would create transparency, as agreed decisions, common documents, reports, and conversations would be visible for all people with given access rights. This would also be useful for both parties regarding changes in personnel. Everyone could keep on track, prepare for upcoming events, and follow the discussion. Clients could, for example, send the same information both to the restaurant manager and to the account manager. The saved conversation history, reminders and annual cycle would also prevent forgetting important issues. To save time, clients want a direct and common communication channel for all the relevant parties and the possibility to see whether, and to whom, important messages have been sent. In addition, both parties brought up that having constantly updated contact details in the portal is important. The company also thought that all the above-mentioned benefits would be important to the clients.

Benefit 4 was defined as “Testimonial support”. The portal can act as a testimonial tool in proving that the contract and service level agreement criteria are fulfilled. This can be done by the dashboard and reporting KPIs as well as by using the action log functionality. The data in the portal can help in investment and budgeting decisions as well as in predicting.

Clients recognized that being aware of the company’s new concepts and renewals would be useful to them. The portal could be the tool to testify that these new concepts are arriving, and constant renewing is happening. The portal would also enable targeting clients with segment related information which is not on the public website.

Benefits include increased financial benefits and increased client satisfaction. Clients saw that the portal could enable faster reaction and communication, in case KPIs are going in an unwanted direction. Both would benefit from predicting the equipment lifecycle. All these have an indirect financial impact as well as the saved work hours from the manual work transformed to automated reports and less email buzz. Work could be focused on core tasks that cannot be done by any system, especially the face-to-face communication with the client. Other financial benefits could be adding sales by triggering the clients, e.g., with new concept ideas by marketing automation. The portal could also be used for reference purposes and to even create new sales. The portal was seen 40in the long run as being able to help in increasing client loyalty and satisfaction and and give a strong competitive edge.

To sum up, based on the analysis of the empirical data, the central findings indicate that both the company and the clients face common challenges, except clients wanting more information on end-user feedback and satisfaction. This finding is of interest as it points out how important it is for the client to track end-user feedback. When it comes to benefits, today’s customer relationship management has several communicational levels and a digital portal tool could have a positive impact on all layers between the company and the client, inside the company and cross-borders to other stakeholders and end-users. Depending on the persona type the client perceives different kind of benefits. In the bigger picture, benefits are multiple as we have discussed above and all of them are linked to enhanced communication: sharing information, making work easier, faster and simultaneous for all parties. This all supports the need of creating a shared platform, a portal, for the B2B business matching the client needs and helping them in their challenges. The MVP features and functionalities support communication and the need to interact with several parties was also shown in all the mindmaps and stakeholder maps drawn by the interviewees and workshop participants. All in all, the importance of enabling interaction with the customer is emphasized in the findings.

3.2. Discussion

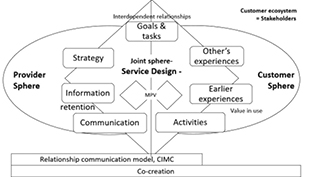

The empirical case study deepened the understanding of the concepts discussed in the theoretical part, which led to a development of a modified theoretical framework (Figure 7): a suggestion for a framework for building a customer-centric B2B client relationship digital tool. The ideal goal of creating a portal system would be for it to link the clients and provider more closely together into an interdependent relationship, according to Woodburn and McDonald’s (2011) client relationship phases, and in this way increase retention. The ability to use Big Data is relevant, and according to Payne and Frow (2005), expanding the current system should be done without disrupting business operations. Grönroos and Tillman (2015) emphasize how companies should focus all their strategies on how to make customer relationships last and influence via positive word of mouth. Grönroos (2007) sees that client 41relationships are for keeping promises and fulfilling them. Service design is the main method placed in the joint sphere presented by Grönroos and Voima (2013). Understanding the client’s life is the basis in service design and in the customer-dominant logic (Heinonen and Strandvik, 2015). Therefore, both the client’s as well as the company’s internal client’s goals, tasks, activities, other people’s experiences, earlier experiences, existing information, and the way things are communicated, are taken into account, according to the factors influencing the formation of customer value-in-use, defined by Heinonen and Strandvik (2015). In this study, service design methods, process and tools are used in stepping into the client’s shoes, and a minimum viable concept is created. As service design in this portal creation concept contains workshops internally and probably later in the future with the clients, co-creation together with the client is seen as important. Sanders and Stappers (2008) define that in co-creation, all the people participating in the design process work collaboratively together, also the users, even when they are not the professional designers. This is how we see it in this study as well—collaboration during the whole service design process in the joint sphere. As a result, a developed framework (Figure 7) is presented below.

Fig. 7 – Theoretical framework for building a customer-centric business-to-business client relationship digital tool (influenced by e.g. customer-dominant logic, service logic and service-dominant logic).

42However, as the results are based on one case company and its clients, and as no statistical methods were used, most of the findings cannot be generalised. Only best plausible explanations (Miles et al., 2014) were sought in this case study, by aiming at conducting rich research with a high level of credibility. It should be also mentioned that only a few clients were interviewed. In order to confirm the validity of the concept, it should be further tested with clients, who did not participate in this study.

Conclusion

The main research question of this case study was: “Customer-centricity — how can it be used in building a digital business-to-business client relationship tool?” The answer to this question was searched by combining insight from the empirical and theoretical part of this case study. Also, the practical development objective was to create a concept for a digital portal tool and to find out “What should the portal be like including ideas, feelings, stakeholders, challenges, features, content and benefits?” Customer-dominant logic and service design were a good combination for a customer-centric approach, seeing the client’s ecosystem and value-in-use (Heinonen and Strandvik, 2015), their thoughts, actions and the reasons behind them. These collectively provided a solid base for this qualitative case study in the field of food service. In the context of business-to-business, we reflect on the question of how customer-centricity can be defined and what are the best practices when building a customer-centric digital tool.

Based on the empirical findings we argue that customer-centricity in the B2B client relationship digital tool creation needs to focus on listening to the clients and their needs. Our findings indicate that the portal can serve as a joint sphere (cf. Grönroos and Voima, 2013) enabling and supporting interaction between the customers and the service provider. A portal that is built based on customer’s requirements and includes functionalities that support interaction and communication enables customer-centricity in the B2B context. Clients need to be involved in the digital tool creation phase to ensure that their needs and 43requirements are taken into account. Their input in ideation is relevant and without this constant insight and feedback, customer-centricity is just a slogan on a company wall.

As a conclusion of the study, how customer-centric business-to-business differs from business-to-consumer client relationship, especially in the context of food service business, is the need to take into account several touchpoints and interaction layers: the business client layer, the end-customer e.g. staff eating in a restaurant, and maybe even a real estate owner. In business-to-consumer, interaction is usually one-layered having the restaurant guest on the other side.

The client relationship in the food service business is also about having a constant dialogue with the client and developing the service together, i.e. co-creating the service. The relationships might last for years and requires trust as the client’s contact person is in charge of large entities. It is more like a partnership in which responsibility on both sides is rather big. Therefore, gathering deep knowledge of the client’s current challenges, job responsibilities and ways of working gives valuable insight into why the tool would be useful for the client. It is to be added that as digitalisation transforms companies, it also transforms their clients’ way of doing. Customer-centric digital tool creation understands this two-folded impact of digitalisation. It considers both sides, and even more layers. Including their own, companies must understand their B2B clients’ digital transformation in order to be customer-centric. To be able to do this they need to know their client’s customer sphere and stakeholders (Grönroos and Voima, 2013) and how they transform. This makes interaction in the B2B context extremely complex as interaction happens between several parties, in different contexts and multiple directions. The multidimensional impact of the digital transformation is also the explanation for interactional needs where features, wishes for content and functionalities rise as Fader (2012) points out. In this study, the identified customer needs formed the basis of the minimum viable product.

As conclusion of the whole study, best practices for a customer-centric digital tool creation contains the following aspects which companies should concentrate on:

–knowing the real reasons why the tool should be created by listening to clients and internal clients (as a digital tool is not 44–the answer for all): knowing what the client needs to do related to the client relationship, why, how often and whom do they report to give valuable insight for the right kind of system design and content. Also, knowing their current challenges and influencing stakeholders is important.

–including the client in framing the concept, testing it, giving constant feedback

–including the client in developing the prototype and the ready solutions – testing, asking for constant feedback and co-creating together with the customer, and making it as a natural part of the business.

–having a transformational mindset with a strong sense of business

–having multidisciplinary people on board who understand the right methods and who are led by a competent and socially skilled project leader.

–creating a minimum viable product.

–using the 80/20 rule and concentrating on the important 20 % customers.

–creating standards and confirming the technical capabilities (incl. integrations) for the tool to be scalable to other contexts.

It is to be mentioned, that in this study all workshops were internal for the case company’s staff but, if possible, clients should be involved in them. The future plan was to run workshops with the clients when refining the concept before the system implementation and integrations.

As for future research, there seems to be a gap in the current scientific literature on account management related to digital solutions, as only a few portal solution related articles and books came up (e.g. Baran and Galka, 2017; Berkovi, 2014; Woodburn and McDonald, 2011, Vlosky et al., 2000) when this article was written, and the literature was mainly related to CRM systems. This raises a question of whether there is a general gap in the amount of B2B marketing related scientific research compared to B2C marketing as Lilien (2015) sees. We ask if customer-centricity still is a rather new approach in the client-related data management, as literature and tools related to account management have been strongly company-driven? Other interesting questions 45include: On the practical level, are companies developing their tools based on their own processes while ignoring what happens on the client’s side? Do they miss the great opportunities of creating a system that serves their clients so well they do not want to change the service provider anymore? Is the significance of the digital transformation still underestimated in traditional service companies? This research points out how customer-centric digital tool creation in the B2B context still needs more scientific research as well as practical hands-on advice for companies. To fill this gap, this article presents the framework in Fig. 7 and uses practical hands-on tools to create the concept. These can be further iterated in other contexts and further research.

In the interviews, the word “easy” came up several times. As a conclusion, a portal built according to client and internal client needs and challenges, can create added value and ease work on both sides, as the amount of data and the fast pace of digital transformation causes pressure on both sides. Everyone is affected somehow, and traditional business frames no longer exist. Digitality is challenging as it changes the touchpoints in the business ecosystem where clients, companies, end-users, and other stakeholders connect. This challenges customer-centricity as knowing the customer is becoming more complex. In the traditional industries, as in the food service industry, we believe that this can cause pain as their core business is not in ICT. Nevertheless, traditional industry also goes through transforming their business and mind-set from production-centricity to service- and customer-centricity. According to this empirical study and experience of it, service design can be used as a “mediator” to facilitate the complexity of the transforming world into understandable elements. With its process and way of doing, thinking and innovating, service design translates complex ecosystems into service blueprints, personas, stakeholder maps and customer journeys.

The definition of customer-centricity could be partly generalizable after further iterations in the traditional food sector’s digital business-to-business context. This is an implication for further studies. In addition, the idea of the concept built in this study can be applicable to other businesses as well e.g. facility management, yet for the concept to be customer-centric, customer insight is needed from that field. The theoretical framework is also possible to extend to future studies around customer-centricism and digital development. Besides, as communication 46and interaction are core issues according to the results in this study, they could be further studied by using the Relationship communication model created by Finne and Grönroos (2017). It addresses the issue of communication and dialogue in client relationships, instead of seeing the client as a passive receiver of a company communication message. All in all, this study offers new insight into digital development, customer-centricism and service design in practice and theoretical discussion in account management.

47References

Agasthi K. (2016), “Client Intelligence Portal Makes Accessing Data Easy. Workforce & Workplace”, Posted 24 June 22. Accessed 19 December 2019. http://sodexoinsights.com/client-intel-ligence-portal-makes-accessing-data-easy/

Arthur L. (2013), “Big data marketing: engage your customers more effectively and drive value”, Accessed 19 December 2019. http://www.marketingmanagement.ir/fa/wp-content/up-loads/2016/11/Lisa_Arthur_Big_Data_Marketing_Engage_Your_CustBookZZ.org_.pdf

Bagheri H., Shaltooki A. A. (2015), “Big data: Challenges, opportunities and cloud-based solutions”, International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, vol. 5, no 2, p. 340-343.

Baltes L. P. (2016), “Digital marketing mix specific to the IT field”, Bulletin of the Transilvania, University of Brasov, Economic Sciences, Series V, vol. 9, no 1, p. 33-44.

Baran R. J., Galka R. J. (2017), Customer relationship management: The foundation of contemporary marketing strategy, 2d edition, New York, Routledge.

Barile S., Lusch R., Reynoso J., Saviano M., Spohrer J. (2016), “Systems, networks, and ecosystems in service research”, Journal of Service Management, vol. 27, no 4, p. 652-674.

Barrett, M., Davidson, E., Prabhu, J., Vargo, S.L. (2015), “Service innovation in the digital age: key contributions and future directions”, MIS quarterly, vol. 39, no 1, p. 135-154.

Berkovi J. (2014), Effective Client Management in Professional Services, Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Bonvillian G. (1997), “Managing the messages of change: Lessons from the field”, Industrial Management, vol. 39, no 1, p. 20-25.

Brinkmann S., Kvale K. (2015), InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing, 3rd edition, Los Angeles, Sage Publications.

Brown J., Isaacs D. (2005), The World Café, Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Carlborg P., Kindström D., Kowalkowski C. (2014), “The evolution of service innovation research: a critical review and synthesis”, The Service Industries Journal, vol. 34, no 5, p. 373-398.

Cheverton P. (2008), Key account management: Tools and techniques for achieving profitable key supplier status, 4th edition, London, Sterling, VA: Kogan Page.

Cooper B. V., Vlaskovits P., Ries E. (2016), The Lean Entrepreneur, Wiley.

Costello, P. (2003), Action research, London, Continuum.

48Curedale, R. (2013), Service Design: 250 Essential Methods, Topanga, CA: Design Community College Inc.

Curedale R. (2016), Experience maps: Journey maps: service blueprints: empathy maps: comprehensive step-by-step guide, Topanga: Design Community College.

Davies U., Wilson K. (2015), “Design Methods for Developing Services: An Introduction to Service Design and a Selection of Service Design Tools. Keeping Connected Business Challenge”, Design Council & Technology Strategy Board: Driving Innovation. Accessed 19 December 2019. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/Design%20methods%20for%20developing%20services.pdf

De Mauro A., Greco M., Grimaldi M. (2015), “What is big data? A consensual definition and a review of key research topics”, AIP Conference Proceedings, 1644: 97–104. Accessed 19 December 2019. http://aip.scitation.org/doi/pdf/10.1063/1.4907823

Dragland Å. (2013), “Big Data – for better or worse: 90% of world’s data generated over last two years”, ScienceDaily, Posted 22 May 2013. Accessed 12 December 2019. http://www.sciencedaily.com-/releases/2013/05/130522085217.htm

Eriksson P., Kovalainen A. (2016), Qualitative methods in business research, 2d edition. London; Thousand Oaks, California, Sage Publications.

Fader P. (2012), Customer Centricity: Focus on the Right Customers for Strategic Advantage, 2d edition, Philadelphia, Wharton Digital Press.

Finne Å., Grönroos C. (2009), “Rethinking marketing communication: From integrated marketing communication to relationship communication”, Journal of Marketing Communications, vol. 15, no 2-3, p. 179-195.

Galbraith J. R. (2011), Designing the Customer-Centric Organization: A Guide to Strategy, Structure, and Process, San Francisco, California, Jossey-Bass.

Girsch-Bock M. (2015), Client Portals Increase Efficiency, Provide Greater Convenience, CPA Practice Advisor, 25(9).

Gosselin P. D., Bauwen A. G. (2006), “Strategic account management: Customer value creation through customer alignment”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, vol. 21, no 6, p. 376-385.

Greengard S. (1997), “Extranets linking employees with your vendors”, Workforce, vol. 76, no 11, p. 28-34.

Grönroos C. (2007), Service management and marketing: Customer management in service competition, 3rd edition, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Grönroos C. (2008), “Service logic revisited: Who creates value? And who co-creates?”, European Business Review, vol. 20, no 4, p. 298-314.

Grönroos C. (2011), “A service perspective on business relationships: The value creation, interaction and marketing interface”, Industrial Marketing Management, vol. 40, no 2, p. 240-247.

49Grönroos C., Voima P. (2013), “Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 41, no 2, p. 133-150.

Grönroos C., Tillman M. (2015), Palveluiden johtaminen ja markkinointi, Helsinki: Talentum.

Grönstedt A. (2000), The customer century: Lessons from world class companies in integrated marketing and communications, New York, Routledge.

Harris R. (2016), “More data will be created in 2017 than the previous 5,000 years of humanity”, Posted 23 December, Accessed 12 December 2019. https://appdevelopermagazine.com/4773/2016/12/23/more-data-will-be-created-in-2017-than-the-previous-5,000-years-of-humanity-/

Heinonen K., Strandvik T., Mickelsson K-J., Edvardsson B., Sundström, E. (2010), “A customer-dominant logic of service”, Journal of Service Management, vol. 21, no 4, p. 531-548.

Heinonen K., Strandvik T., Voima P. (2013), “Customer dominant value formation in service”, European Business Review, vol. 25, no 2, p. 104-123.

Heinonen K., Strandvik T. (2015), “Customer-dominant logic: Foundations and implications”, Journal of Services Marketing, vol. 29, no 6/7, p. 472-484.

Heinonen K., Strandvik T. (2017), “Reflections on customers’ primary role in markets”, European Management Journal, vol. 36, no 1, p. 1-11.

Higgins J. (2011), 6 steps to developing an effective client portal strategy, CPA Practice Advisor, vol. 21, no 1, p. 30-32.

Higgs A. (2015), “Find the key to client portals”, Cover Magazine. 13.

Holtzblatt K., Koskinen I., Kumar J., Rondeau, D., Zimmerman, J. (2014), “Design methods for the future that is now: Have disruptive technologies disrupted our design methodologies?”, in Proceeding, One of a CHIind. CHI EA ‘14 CHI.’14 Extended Abstracts on “Human Factors in Computing Systems”, Toronto, Canada, p. 1063-1068.

Johnson M. D., Selnes F. (2004), “Customer Portfolio Management: Toward a Dynamic Theory of Exchange Relationships”, Journal of Marketing, vol. 68, no 2, p. 1-17.

Kaner S., Lind L., Toldi C., Fisk S., Berger, D. (2014), Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-making, 3rd edition, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, A Wiley Brand.

Kepczyk R. H. (2008), “Client Portal Opportunities”, CPA Practice Management Forum, vol. 4 no 6, p. 5-9.

Ketokivi M., Mantere, S. (2010), “Two Strategies for Inductive Reasoning in Organizational Research”, Academy of Management Review, vol. 35, no 2, p. 315-333.

50Kimbell L. (2011), Case Study 08: From Novelty to Routine: Services in Science and Technology-based Enterprises, in: Meroni, A., Sangiorgi, D. (eds.) Design for Services. Surrey: Gower Publishing Limited. MPG Books Group, 105-111.

Krippendorff K., Bock M.A. (2009), The content analysis reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kuosa T., Westerlund L. (2012), Service design: On the evolution of design expertise, Lahti, Lahti University of Applied Sciences.

Leavy B. (2017), “Customer-centered innovation: Improving the odds for success”, Strategy & Leadership, vol. 45, no 2, p. 3-11.

Lilien G. L. (2016), “The B2B Knowledge Gap”, International Journal of Research in Marketing, vol. 33, no 3, p. 543-556.

Lukka K. (2003) “Case study research in logistics”, Publications of the Turku School of Economics and Business Administration, Series B, p. 83-101.

Mager B., Sund T-J. (2011), “Special Issue Editorial: Designing for Services”, International Journal of Design, vol. 5, no 2, p. 1-3.

Mahmud I, Rawshon, S., Rahman Md. J. (2011), “Mind Map For Academic Writing: A Tool To Facilitate University Level Students”, International Journal of Educational Science and Research, vol. 1, no 1, p. 21-30.

Marvin H. J. P. (2017), “Big data in food safety: An overview”, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, vol. 57, no 11, p. 2286-2295.

McDonald M., Millman T., Rogers B. (1997), “Key account management: Theory, practice and challenges”, Journal of Marketing Management, vol. 13, no 8, p. 737-757.

Miles M. B., Huberman A. M., Saldana J. (2014), Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook, 3rd edition. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Millman T.,Wilson K. (1995), “From key account selling to key account management”, Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science, vol. 1, no 1, p. 9-21.

Nummi P. (2012), Fasilitaattorin käsikirja, Helsinki: Edita Publishing Oy.

Ojasalo K., Moilanen T., Ritalahti J. (2014), Kehittämistyön menetelmät: Uudenlaista osaamista liiketoimintaan, 3rd edition, Helsinki, Sanoma Pro.

Osterwalder A., Pigneur Y., Clark T. (2010), Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Payne A., Frow P. (2005), “A Strategic Framework for Customer Relationship Management”, Journal of Marketing, vol. 69, no 4, p. 167-176.

Reason B., Løvlie L., Flu M. B. (2016), Service design for business: A practical guide to optimizing the customer experience, Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

51Ries, E. (2011), The lean startup: How constant innovation creates radically successful businesses, London: Penguin.

Rogers D. L. (2016), The digital transformation playbook: Rethink your business for the digital age, New York, Columbia Business School Publishing.

Sanders E. B.-N., Stappers P. J. (2008), “Co-creation and the new landscapes of design”, CoDesign, vol. 4, no 1, p. 5-18.

Schieffer A., Gyllenpalm B., Issacs D. (2014), “The World Café: Parts One & Two. World Business Academy”, Transformation, vol. 18, no 8.

Schneider J., Stickdorn M. (2010), This is service design thinking: Basics – tools – cases, Amsterdam: BIS Publishers.

Secoya (2017), “Software as Service”, Accessed 19 December 2019. https://www.se-coya.dk/cases/iss

Seymour R-S. (2010), “Capturing and Retaining Knowledge to Improve Design Group Performance”, Journal of Research Practice, vol. 6, no 2, article M15.

Shah D, Roland R.T., Parasuraman A., Staelin R., Day G. S. (2006), The Path to Customer Centricity, Journal of Service Research, vol. 9, no 2, p. 113-124.

Smaply, (2016), “Visualize customer experience – quick start guide. Service design manual”, Version 1.2, Accessed 19 December 2019. https://s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/cxindustries-website-assets/smaply/downloads/Smaply-Explainer-A5-02-DS.pdf

Tschimmel, K. (2012), “Design Thinking as an effective Toolkit for Innovation”, ISPIM Conference Proceedings, Manchester, The International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM), p. 1-20.

Tuulaniemi J. (2011), Palvelumuotoilu, Helsinki, Talentum.

Ulaga W. (2018), “The journey towards customer centricity and service growth in B2B: a commentary and research directions”, AMS Review, vol. 8, no 1-2, p. 80–83.

Ulwick A. W. (2017), “Outcome-Driven Innovation® (ODI): Jobs-to-be-Done Theory in Practice”, White paper by Strategyn, Accelerated growth. Delivered. Accesses 19 December 2019. https://1ogdym1ia11w3ph60o1qk1l9-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/files/what-is-outcome-driven-innovation-strategyn/what-is-outcome-driven-innovation-strategyn.pdf

Vargo S. L., Lusch R. F. (2008), “Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 36, no 1, p. 1-10.

Vargo S. L., Lusch R. F. (2017), “Service-dominant logic 2025”, International Journal of Research in Marketing, vol. 34, no 1, p. 46-67.

Vlosky R. P., Fontenot R., Blalock L. (2000), “Extranets: Impacts on business practices and relationships”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, vol. 15, no 6, 438-457.

52Witell L., Snyder H., Gustafsson A., Fombelle P., Kristensson P. (2016), “Defining service innovation: A review and synthesis”, Journal of Business Research, vol. 69, no 8, p. 2863-2872.

Womack J. P., Jones D. T. (2003), Lean thinking: Banish waste and create wealth in your corporation, 1st Free Press edition, revised and updated, New York, Free Press.

Woodburn D., McDonald M. (2011), Key account management: The definitive guide, 3rd edition, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Yin R.K. (2012), Applications of case study research, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

1 Corresponding author. Senior Lecturer. Address: Ratapihantie 13, 00520 Helsinki, Finland. Tel. +358 40 488 7119. Email: eliisa.sarkkinen@haaga-helia.fi