Co-création des services public Pourquoi et comment ?

- Type de publication : Article de revue

- Revue : European Review of Service Economics and Management Revue européenne d’économie et management des services

2020 – 1, n° 9. varia - Auteurs : Mureddu (Francesco), Osimo (David)

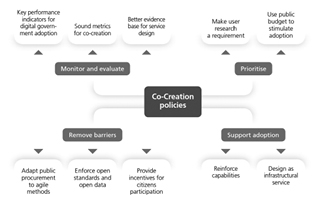

- Résumé : Cet article propose une feuille de route en dix étapes pour un gouvernement numérique centré sur l’utilisateur et la co-création. Quatre domaines sont abordés: 1. Prioriser l’adoption, en faisant de la recherche des utilisateurs une exigence des services publics et en utilisant le budget public pour stimuler la co-création ; 2. Soutenir la mise en œuvre, en renforçant les capacités dans l’administration et en faisant de la conception de services un service d’infrastructure ; 3. Supprimer les barrières, en adaptant aux marchés publics les méthodes agiles, en instaurant des normes sur l’open standard et l’open data, en incitant à la participation des citoyens ; 4. Suivre les résultats, en mesurant les indicateurs de performance du gouvernement numérique, en appuyant sur des preuves la conception de services publics, et en mesurant l’adoption de la co-création par l’administration publique.

- Pages : 177 à 200

- Revue : Revue Européenne d’Économie et Management des Services

- Thème CLIL : 3306 -- SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES -- Économie de la mondialisation et du développement

- EAN : 9782406106043

- ISBN : 978-2-406-10604-3

- ISSN : 2555-0284

- DOI : 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-10604-3.p.0177

- Éditeur : Classiques Garnier

- Mise en ligne : 06/05/2020

- Périodicité : Semestrielle

- Langue : Anglais

- Mots-clés : Services publics, gouvernement digital, co-création, valeur

Co-Creation of Public Services

Why and How?

Francesco Mureddu,

David Osimo

The Lisbon Council1

Introduction

In 2011, public-sector workers in Barcelona faced an interesting dilemma. They wanted to improve the quality of air and water and cut down on noise pollution. But they lacked the data they needed to do so. And they didn’t have sufficient buy-in from the city’s own citizens, many of whom were not fully informed about deteriorating environmental conditions which – if they knew about them – could have served as a basis to change harmful patterns of behaviour and catalyze action in key areas. The result was a revolution in thinking which is having far-seated repercussions even today. Through a project called Smart Citizen initiated by Fab Lab Barcelona, the city produced and distributed a set of “smart citizen kits,” which consisted of sensors that citizens could use to measure light intensity, air temperature, toxic gas, humidity and noise pollution. It came with an Arduino computer board, a mobile app, a custom-built application programming interface 178(API) for uploading data and even a special Wi-Fi system for interested citizens to use. The results are impressive, and the application evolved through crowdfunding into a fully-fledged platform that is used as unique data source by research centres and cities all over Europe. Had the Barcelona civil service discovered a silver bullet – a magic solution around which all citizen-state problems could be solved and better outcomes achieved for everyone? Hardly. But what they had done was intriguing – and potentially very far reaching. In the intervening time, a new generation of academics and public sector consultants have devoted themselves to the study and iteration of “co-creation” – a complex process in which citizens stop simply consuming government services and start to play an active role in their design, delivery and execution. Related to this has been a drive towards “design thinking” in the production and dissemination of public services. This is an iterative process, where a service is created based on feedback from citizen/consumers, often in collaboration. Later, the service itself is evaluated not by sloppy metrics covering blanket adoption and box ticking, but by real-world efforts to map the way the service is developed, analyse the way it is being implemented and use the information gained to deliver a better service. Over and over and over again.

Today, the challenge for public administration is fundamentally different. Co-creation has captured the imagination of many, and the authors of this paper are veterans of a movable feast of high-level conferences convened to discuss and analyse these emerging public-sector tools at an abstract, expert level. But the fundamental challenge remains: How do we turn co-creation from a faddish idea popular with analysts, experts, fab labs and the like into a reality for Europe’s 508 million citizens? In other words, how do we take the pockets of local success and deliver them to Europeans at scale? And how do we do that despite the notorious conservatism of many public administrations, and the fact that the public sector remains – and sometimes for good reason – so terrified of failure that initiative is often the exception and innovation seldom the rule? The fact is, the academic literature and real-life experience with co-creation has moved well beyond the theoretical level (Osborne et al., 2013; Bason, 2018; Voorberg et al., 2015). Today, we possess many effective, well tested toolkits, ready to be deployed and capable of delivering results, as well as a wealth of on-the-ground 179experience available to guide and shape co-creation initiatives for any administration ready to take the plunge. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Observatory of Public-Sector Innovation, for one, lists more than 100 toolkits available for service design in the public sector.

The reason for uneven adoption in some places may well lie in a mis-conception: some believe co-creation is at heart an experimental, pioneering initiative belonging only to disruptors. Today, co-creation is a mature subject area. The key principles have been codified. There are standardised methodologies, some of which we will touch on later in this policy brief. There is also an extended theoretical and applied research effort underway, led in many places by members of the Co-VAL consortium whose research informed this policy brief.

And there is a solid professional community, ready to deliver, and staffed by people with clearly identified job profiles, such as “user researcher” and “service designer.” There are even success stories of entire countries that scaled up design thinking at national level, such as Italy’s Government Commissioner and Digital Transformation Team and the United Kingdom’s legendary Government Digital Services. Perhaps the easiest way to understand co-creation is to think of it in terms of the way software has come to be used and developed. Agile management methods, which rely on smaller, shorter projects with frequent iterations that incorporate feedback from users, have become the standard (Mergel, 2017). There is simply no large online software that is not iterated frequently, based on consumers’ experience and feedback. This policy brief is divided into four sections. In Section 1, we will define co-creation and look at why it is important. In Section 2, we will briefly discuss two leading schools for development and touch on some concrete tools and policy choices awaiting civil services ready to dive in and adopt. In Section 3, we put forward policy recommendations for delivering genuinely user-centric digital government, arguing that it is time to put co-creation at the core of government functioning. And in Section 4, we will look at some policy pitfalls – a not-unimportant area for civil services contemplating change in delivery fields that touch so directly on so many people’s wellbeing.

1801. Why co-creation matters?

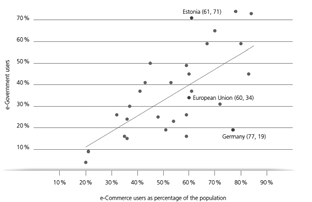

In the opening scene of “Bodyguard,” a popular British television series, Police Sergeant David Budd briefly looks up the voting history and biography of the minister who has just been appointed to serve over him. The website he uses – www.theyworkforyou.com – is a real website, set up in 2004 by a group of volunteers fed up by the lack of usability of the official parliament website. This new unofficial service rapidly became the de facto standard for all people interested in the activity of members of parliament; even parliamentary staff now use it instead of the official website. Partly because of the government-run websites’ notorious clunkiness – and the difficulty some public administrations encounter when they try to design web-based services that citizens are comfortable using – the uptake of online public services remains low, with only one in three European Union citizen claiming to have completed an online government transaction in the last 12 months2. This is not the result of lack of skills or confidence among citizens, as is demonstrated by their high level of adoption of e-commerce and social media. Many commercial websites, often under the impulse of competition from new web-only services, have made major improvements in becoming intuitive and usable. But government services remain difficult to use. In fact, the adoption gap between private and public services is widening. In 2018, 60 % of Europeans made purchase online while 34 % made e-government transactions. That adds up to a 26 % user gap in 2018, up from as little as 15 % in 2008. See Figure 2 below for more.

181

Fig. 1 – e-Government vs e-Commerce adoption 2018 (Source: EUROSTAT).

What’s more, this gap is the average of very different performances in different states as shown by the two extremes. In Germany, for example, 77 % of adults use e-commerce while only 19 % use e-government services. In Estonia, the situation is the opposite; more people (71 %) use e-government services than e-commerce (61 %). In other words, the gap is not a given, and there are countries where online public services are as much a part of citizens’ daily lives as commercial services, or even more3.

The lack of e-government uptake in many places is a long-standing challenge, and the solution has been known for a while. It lies in a Copernican Revolution that puts the users, not the administration, at the center of service delivery. In 2008, when the first iPhone was being released in Europe, European Union and European economic area ministers met in Malmö to sign The 2009 Malmö Ministerial Declaration, which committed them to designing and rolling out “e-Government services designed around users’ needs.” In 2017, when the tenth generation iPhone X was being launched, EU and EEA members committed 182again to a set of “user-centricity principles for design and delivery of digital public services” in The 2017 Tallinn Ministerial Declaration on eGovernment4. The consistency between declarations nine years apart says more about the slowness of progress than the strength of the high-level commitment.

To be fair, digital government has come a long way in 10 years. There have been clear improvements in many services, as demonstrated not only by the increase in the online availability but also by the improvements in interoperability and usability (see European Commission, 2019; Tinholt et al., 2018). And the recognition of the importance of “user centricity” as a guiding principle has led to a proliferation of individual initiatives, such as innovation labs and broad scale urban experiments, but these improvements have remained in most cases confined to individual countries, cities or even individual services. They have not scaled. The first challenge, when addressing co-creation, is defining it. The term is over-used, so that almost every government service these days claims to have been “co-created”. But the reality is that without more effective implementation and commitment that runs beyond lip service, there is the risk that co-creation moves over time to effective oblivion without having had its moment of genuine impact. To be sure, co-creation can be done in different ways and includes a variety of degrees of involvement of users. Co-creation does not necessarily mean that citizens self organise and deliver services on their own. Indeed, citizens are not always willing or able to participate in such complicated processes. Fortunately, co-creation can also include formats where there is no need for users to co-create deliberately. This can happen by better using data and statistics on the way services are being taken up to make them easier for citizens to use. Concretely, it is possible to distinguish between two types of co-creation: “intrinsic” co-creation, in which the participation of citizens in the process is passive (i.e. the individual is not aware of their role), and “extrinsic” co-creation, in which the participation is active. In the case of “intrinsic” co-creation, individuals can be engaged in passive co-creation when the public services they access are studied to bring improvements in design. Extrinsic co-creation, by contrast, is built around co-design, i.e., the active involvement of citizens in improving 183existing services, in innovating new forms of public service delivery and in actually collaborating on the management and delivery of those services (Osborne et al., 2016). See Table 1 for a schematic rendering.

Tab. 1 – Defining co-creation.

|

Intrinsic co-creation |

Extrinsic co-creation |

|

|

Co-construction |

Co-design |

Co-production |

|

e.g. User-centred design Log analysis Agile methods |

e.g. Participatory design E-consultation |

e.g. Volunteering Open data apps Living Labs |

|

Citizens participate passively |

Citizens participate actively through feedback and ideas |

Citizens participate actively and take part in implementation |

This conceptual model, and the notion of co-creation in general, applies to all public services, whether analog or digital. But to be sure all digital services can uniquely benefit from co-creation. Co-construction can also benefit from data generated in real time by the interaction of the user with public services. And co-design can benefit from tools such as a participatory design. Most importantly, open data and the open APIs built around them can allow citizens to build entirely new services on top of government data. The importance of co-creation lies in the recognition that human needs and behaviours are increasingly complex and often unpredictable. Governments cannot expect to have sufficient knowledge to design services and policies that work in a vacuum. The reality – not only of public services, but of society and the economy at large – is that constant tweaking and tinkering are needed. New needs emerge, and they have to be responded to. Co-creation, in its different forms, allows for delivering better services by capturing user needs and behaviour and adapting to it dynamically. Obviously, this flexibility is greatly enhanced by new technology, which allows services to be dynamically recomposed and delivered, feedback to be gathered in real time and adjustments to be made at low cost even after the launch of the service – just as smartphones periodically upgrade their system. But the importance of co-creation is in the capacity to use previously unexploited citizens’ resources and capabilities. Obviously, as a user of 184public services, citizens have a unique perspective on the quality of public services. It is simply impossible for governments to place themselves in the position of users. And it is fundamental that, through intrinsic and extrinsic co-creation, this knowledge is captured and put to use. Co-creation also has the potential to leverage unique competences for users to add value to public services. Citizens can help providing real time information on the state of the roads through applications such as fixmystreet.com. They can provide unique in-depth knowledge on specific issues; they can help changing the behaviour of other citizens; and they can develop new applications based on government data, as in the case of the https://openbilanci.it5.

Beside a positive definition, it is worth pointing out a set of commonly held misconceptions on co-creation. First, co-creation is not about government outsourcing their functions to self-organised citizens. If anything, co-creation requires more leadership from government. And the most widely adopted form of co-creation does not entail a proactive role for citizens, but the adoption of suitable user research methods. Actual co-production of public services is far less common than the lighter forms of co-construction and co-design. Second, co-creation is not purely “bottom-up,” simply asking any user to state his/her needs or put forward ideas about how to solve a problem or to expect them to act by themselves. There are clear, well-structured methodologies to detect needs and co-design solutions. Organising a workshop is not sufficient to claim co-creation. One of the paradoxes of co-creation is the idea that to obtain well designed and user-centric public services one can simply ask a question on social media. The “build-it-and-they-will-come” attitude does not work with co-creation, just as it doesn’t work for public services. Further, it is not about “radical openness.” Opening up is a prerequisite for co-creation, but openness to be effective needs to be well designed and iterative. Moreover, the amount and type of people to involve has to be carefully designed. Co-creation does not necessarily mean that anyone can be involved. It can be organised with a limited set of people who contribute. And it does not refer to citizens only, but to any user type, including companies and other public administrations. Moreover, co-creation is not about technology. Co-creation applies to both digital and analog services and this distinction is today 185increasingly irrelevant – there are few services that have no digital component. Most importantly, co-creation means starting the process from users’ needs and problems, not from technological solutions. Of course, digital technology is in itself a useful instrument for co-creation, because it can help the possibility of both intrinsic and extrinsic participation. But even when it comes to purely digital services, one of the most impactful results of co-creation is often just to write in a more comprehensible manner, avoiding jargon. Finally, co-creation is not a form of frontier innovation for pioneers. It is a set of methods that can be (and actually should be) applied to any service by any organisation. There are standardised methodologies, in particular for user centred design and co-design.

Apart from the confusion in the definition of co-creation, there is also a lack of reliable data on its adoption. This is yet another confirmation that co-creation is still treated as a frontier activity rather than as a core function. A review of available metrics, produced as part of the ongoing Co-VAL research, shows a variety of inconsistent indicators that only marginally touch upon co-creation. Many of them were conceived almost 10 years ago:

–The 2009 “Measuring Public Innovation in the Nordic Countries (MEPIN) Survey of Innovation” by approximately 2,000 public sector entities in the five Scandinavian countries included one question on the importance of “user satisfaction surveys (or other user surveys)” as an information channel for innovation activities. The percentage of respondents attributing a high importance to user satisfaction surveys varied from 27 % in Norway to 40 % in Iceland.

–The 2010 European Innobarometer survey with 3,500 responses from public sector agencies, asked about the importance of “citizens as clients or users” as an information source for developing innovations. For all 27 EU countries, 46 % of respondents stated that citizens were a ‘very important’ information source. There was little variation by the function of the agency, with the lowest reported percentage of 44 % observed for general government activities and the highest percentage of 52 % for agencies focused on education.

–In 2010 Nesta conducted a pilot survey of innovation carried out by local authorities and National Health Service (NHS) trusts in 186–England, obtaining responses from 64 NHS trusts and 111 local authorities. A report on the Nesta results shows that service users are found by 66 % of local councils to be an important source for what concerns the elaboration of ideas for innovation and that 58 % of local councils involve service users in the development of innovations.

2. Co-creation: approaches,

tools and application cases

There are two principal ways for a public administration to “co-create” public services:

1. “service design,” which is the systematic application of design methodology and principles to public services with the goal of designing those services from the perspective of the user,

2. so-called “living labs,” which are independent administrative units located within the public sector but capable of operating autonomously and defining their own innovative targets and working methods.

2.1. The ‘Service-Design’ approach

There is a clear distinction between the service design and living labs approach. Service design, for one, is a methodology to facilitate the inclusion of external stakeholders in the design of the services. In this regard, service design is a key agent of public sector transformation and a core element of a learning process, and in fact builds on two main assumptions. The first assumption is that the “most relevant actor that may be significantly transformed through and during the design process is the organisation that leads the process itself” while the second assumption maintains that the “design process can be conceived as a learning process, as people and organisations learn how to deal with innovation by taking part in designing experiments” (Rizzo et al., 2017). Drawing on the cutting-edge work of Marc Stickdorn, service design is characterised by five main principles:

1871. “user-centricity,” as services should be experienced through the customer’s eyes;

2. co-creation, as all stakeholders should be included in the service design process;

3. sequencing, as the service should be visualised as a sequence of interrelated actions;

4. evidencing, as intangible services should be visualised in terms of physical artefacts;

5. holism, as the entire environment of a service should be considered in the analysis” (Stickdorn, 2010).

So while public-service logic theorises value and value creation in public-service contexts, service design can be used to explore what users really value and suggest how such insights can be used to improve service systems.

2.2 The ‘Living Labs’ approach

Following the example of the European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL), “living labs are defined as user-centred, open-innovation ecosystems based on a systematic user co-creation approach, integrating research and innovation processes in real life communities and settings”6. More extensively, “living labs can be understood as settings or environments for open innovation, which offer a collaborative platform for research, development and experimentation in real-life contexts, based on specific methodologies and tools, and implemented through specific innovation projects and community-building activities. Living labs are driven by two main ideas: 1) involving users as co-creators of innovation outcomes on equal grounds with the rest of participants, and 2) experimentation in real-world settings.” (Gascó, 2017).

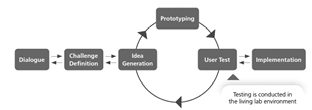

A good example is the Torino City Lab, an initiative-platform that creates an environment for testing innovative solutions for urban living in real conditions. The public administration provides support to private companies in facilitating testing operations in real conditions in frontier technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics, autonomously driven and connected vehicles, fifth-generation telecommunication networks (5G), the Internet of Things and drones. The interesting characteristic 188is that the lab’s work is open to all of the city. Companies, end users and citizens are involved in testing through “calls for action”. Specific initiatives include the collection of environmental data through low cost portable sensors and the improvement of government service-based apps. Central to the living lab concept is the role of co-creation between diverse typologies of stakeholders in real-life settings. In fact, living labs are integrative contexts for co-creation and innovation that are real-life phenomena (the “living” part of living labs) while at the same time separate from everyday activities (the “lab” part). As labs, they remove pressures, risks and ethical concerns related to innovation from day-to-day activities in public administration. However, as close-to-reality phenomena, they aim to draw on everyday experiences and actors’ interests and perspectives. For instance, the Danish Mindlab has made extensive use of user-centred design for creating a culture of experimentation and risk-taking across government, in areas such as education, employment and digital government. For more on how the living-lab method works, see Figure 3 below (Yasuoka et al., 2018).

Fig. 3 – The Living Lab methodology (Source: Yasuoka et al., 2018).

1893. A ten-step programme: placing users

at the centre of public services

As we have seen, there is consensus over the need to place users at the center, and greater involvement of users is present in all reform efforts of the last thirty years (see the “In Focus” box for a brief history). The problem is turning this declaration of intent into large scale adoption. To do that, we need to make sure that co-creation is taken seriously and not treated as a “nice-to-have” feature but as a fundamental requirement for successful public services. The overarching message of this policy brief is that co-creation is not some mysterious and obscure frontier research activity only available to self-appointed “innovators.” There is a consolidated body of knowledge and techniques. There is a large community of experts.

It is a clearly defined process that requires the same things as any other policy priority: leadership, resources and skills. As Michael Slaby, chief technology officer of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, puts it: “It’s not complicated, it’s just hard”7.

The goal is to move co-creation from the periphery to the centre of public-sector innovation, to ensure that ultimately, there will be no public service without any co-creation element. Obviously, co-creation should be intended in the widest sense, as outlined in this policy brief, including intrinsic co-creation instruments invisible to users.

We have examples of countries which have managed to place co-creation at the core, and it is no accident that Scandinavian countries lead both in digital government uptake and design thinking8. But the UK provides the best example of scaling up – of actually moving co-creation from the periphery to the core. It did so by creating a dedicated team, largely brought in from the outside, with extraordinary 190political endorsement (reporting to the prime minister) and with a clear mission – in that case, to make the government’s online presence consistent.

Building on these experiences, we propose a 10-point roadmap built around four key themes, summarized in Figure 4.

Fig. 4 – Co-creation Policies (source: authors’ elaboration).

3.1. Prioritise adoption

1) Make user research a requirement for public services. This is a minimum requirement for effective government. It could include the introduction of a “user test” for public services, similar to the EU’s “SME test” for regulation. Just as the “think small first” principle requires that any regulatory intervention is accompanied at an early stage by an assessment of the impact on small and medium-sized enterprises, any intervention in the provision of public services (online or off) should be accompanied by a proper analysis of user needs catalogued using service-design methods – a “think users first” principle (European Commission, 2008). And following the example of “better regulation”, the European Commission and EU member states should develop guidelines 191and toolboxes for public administration to use in order to actually fulfil this new “user test” principle (European Commission, 2015).

2) Use the public budget to stimulate adoption of co-creation. Co-creation, at the level of fully-fledged user research, should become a prerequisite for funding government innovation. No innovation in public services should happen without proper use of design methods, at least for assessing user needs. Any public body funded government innovation initiatives should make it a conditional requirement to introduce co-creation methods in the project. At European level, the EU structural funds should make funding conditional on the adoption of proper co-creation and co-design methods. Clear definition and guidelines on co-creation should be provided, and adequate reporting mechanisms should be in place to ensure implementation.

3.2. Support implementation

3) Reinforce capabilities in public administration. Upscaling of co-creation requires public sector managers to have specific in-house capabilities and tools. Among others, these include expertise in service blueprinting to determine the line of visibility between what is and is not visible to users and the ability to identify the “touch” points for service users; ethnographic and observational research to identify the subjective experiences of users; constructing personas by using data obtained from interviews with users to construct a persona for a fictitious user; visualisation and mapping, specifically service blue-printing and customer journey mapping (Trischler and Scott, 2016). In this regard, public administration needs to hire external experts that are able to apply methodologies such as design thinking in the elaboration of public services. This entails making recruitment processes in public administration more flexible. So far, most digital teams were created through ad hoc exceptions and extraordinary recruitment powers, but if we want co-creation to scale, it cannot be done by bending the rules and finding exceptions; it will require adapting recruitment mechanisms. On top of that, there is a need to establish organisational learning processes which ensure that participative outputs feed back into the process and shape future service propositions or contribute to new innovations.

1924) Establish service design as an infrastructural service in each member state. A way to generalise the use of co-creation and specifically of service design in each EU member state could be the establishment of “co-creation support services” (mirroring other infrastructural services such as payments and authentication platforms) responsible for providing direct support to local and central public administrations that are involved in the establishment of new services and that lack the internal capabilities. To this end, the service-design team would elaborate and make available toolkits and guidelines to be used by public administrations, and will also provide public administration with direct support. Clearly, cocreation is not as scalable as other infrastructural services as it entails substantial human effort. But the costs could be covered as part of the above-mentioned funding mechanisms that will now require co-creation methods to be used.

3.3. Remove barriers

5) Adapt public procurement to agile development methods. As it stands, public procurement procedures struggle to deal with design processes. Procurement procedures aim at minimising risk, sterilise contact between buyers and tenderers and typically follow a linear “waterfall” process where requirements are defined ex ante and changes are the exception rather than the rule – the opposite of a service design process. If the externalisation of design and delivery of services is extensive, an organisation and its employees may actually be prevented from learning from interaction with users, as well as from better designing the new services capturing factors that reside in their implementation at later stages. Public administration should adopt innovative and experimental public procurement processes allowing them to collaborate with the whole network of actors potentially involved in the delivery of the service. This would amend current rules of public procurement, according to which actors involved in the design of the service then cannot take part in its delivery.

6) Enforce the norms on open standards and open data. Co-creation can be made impossible by the adoption of proprietary standards solutions as well as the reluctance to open up government data. Open data, standards and software enable citizens to co-create services on their own terms, as widely demonstrated by the proliferation of civic apps. In this 193respect, governments should define clear principles regarding ownership and re-use of data and service components, as well as provide indications on accountability for quality of services, while at the same time recognising innovation and risk taking as key components of governing.

7) Provide the right incentives to ensure citizens’ participation. For citizens, there are a number of factors influencing their participation in co-production activities, such as ability and level of information (Voorberg et al., 2015). For instance, the role of information has been acknowledged both at the point of access and during the process of interaction as influencing citizen’s capacity to actively engage. In this regard, it has also to be noted that material rewards may fall short when applied to the public sector and other intrinsic values might influence citizens’ willingness to contribute to public-service production. Indeed, a recent experimental study on financial incentives has found only a limited effect of such rewards on stimulating citizen’s willingness to co-produce (Voorberg et al. 2018). As shown by forthcoming research carried out within the scope of the Co-VAL project, information on the co-creation process delivered through direct means, possibly by beneficiaries of own efforts, strongly affects citizens’ willingness to co-produce, while immediate and individually enjoyed benefit has no effect on their effort (Oprea, 2019)9. In general terms, citizens are stimulated to take part in co-creation activities when they see that their effort is recognised and taken into account and when they feel the effects of it.

3.4. Monitor results

8) Make metrics on adoption the key performance indicators of digital government. Metrics are a fundamental policy instrument in Europe, especially in areas that do not fall under the competences of the EU such as public services. Digital government today is measured through different indicators, such as the percentage of public services that are available online or the availability of open government data. Making adoption of digital services the central metric will incentivise 194European governments to place users genuinely at the centre. Moreover, the metrics should not be elaborated through surveying citizens, but by using data automatically generated by online services, namely the percentage of service transactions delivered online. Many member states already do this, but data are not standardised. For this reason, every digital government service should publish adoption metrics openly and in real time, and EU member states should work towards standardising such indicators. At the European level, data on uptake of digital service should be included in the list of “high-value datasets” defined in the latest proposal of the revised directive on public sector information.

9) Provide a clear evidence base for service-design in government. The adoption of co-creation practices is resource consuming both in terms of dedicated time and effort, as well as in terms of monetary resources. Therefore, it is very important to present a clear evidence base showing the advantages of investing in co-creation. It is ironic that public sector innovation labs strive to bring an experimental culture to public services, but there is a lack of experimental evidence about the effectiveness of co-creation.

10) Provide sound metrics on adoption of co-creation by public administration over time. The only metrics available are vague and ambiguous, and do not provide a proper definition of co-creation. The Co-VAL project will provide a first basis in 2020 when it publishes the results of a dedicated survey and the Co-VAL Dashboard, which will track co-creation projects across Europe10. Precisely because co-creation is now mature, it is possible today to define standard indicators, such as the number of users involved and the number of co-creation sessions held.

1954. The “don’t’s” of co-creation and the need

for a civil service that can deliver

To make the best out of co-creation, one should be aware of the challenges. The participation of citizens in public service production and delivery is challenged by power asymmetries and the failure to embed participation as a core structural process of public service design and delivery. The asymmetry originates through the differentiation of roles between public managers, stakeholders and service users, with power generally being retained and exercised by the former two. In the old model, public managers held the organisational skills, knowledge, capacity and creativity to influence decision-making and produce solutions (Terry Larry, 1993). They were contrasted against service users who were thought to have limited capacity, knowledge and expertise to shape public services (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2004). Sometimes “transformative leaders” were placed in a dominant position, “serving” the needs of citizens and ultimately creating value. However, this conceptualisation suggested public managers were working for rather than working with service users, implying an implicit relationship of dependency rather than a collaborative and deliberative approach (Meijer, 2016). Furthermore, citizens’ participation has oftentimes created new sub-elite groups who have exclusive access to decision-making. Such groups are limited largely to “experts” or “representatives” rather than including the wider citizenry (Chen et al., 2013). In this regard, citizens’ participation can lead to distributing power disproportionately to organised groups and potentially further marginalising others (Jacobs, 2014). Considering structural changes, public service reforms from the 1960s onwards have centred predominantly on institutional change via decentralisation, networks and direct citizen participation or deliberation with the aim of empowering citizens or consumers to varying degrees (for a history of public-sector reform definitions, see In Focus: Theories of Public Engagement, – Then and Now). In fact, despite specific iterations within each narrative, participation has continued to be consigned to the periphery of public service design and delivery. In theory, participation empowers citizens through the structural 196integration of participative and deliberative mechanisms. However, participation through empowerment is restrained by the enduring hierarchical power structures of both representative democracy and public management, with the scope and impact of participation being determined by public-service staff (Vigoda, 2002). The implication is that participation is side-lined in public service design and delivery. In short, empowerment through structural change has not been effective in transforming public service production into a participative process, because the conceptualisation of empowerment necessitates that those in government share power (Callaghan and Wistow, 2006). More recent research suggests that participation, upwards through representative democracy and horizontally through deliberation and co-production, will result in a shared public interest which can be translated to achieve public value outcomes. However, some scholars fail to consider how these participative structures may be embedded in closed decision making structures, sometimes forwarding consumer mechanisms of participation or emphasising network structures that are occupied predominantly by professionals.

This has clear negative implications for the inclusiveness of participation (Shaw, 2013). Similarly, the plurality of actors introduced by networks opens horizontal channels of influence for professionals or organised groups. Downwards channels of influence towards citizens such as co-production, however, have remained closed or at best controlled by those sitting on networks (Alford, 2009).

Focussing more specifically on the co-creation of value, there are four main challenges emerging for participation. First, value can be co-destructed, where the co-creation process is mismanaged or services are poorly designed (Meynhardt, 2009). This happens as front-line staff can have a negative effect on the service experience and their role in the value creation process is therefore crucial. The service user can also destroy value where they refuse to participate according to procedures or rules set out by the public sector organization (Osborne et al., 2015; Skålén et al. 2018).

Second, different dimensions of value can be served in different measures. For instance, a public-sector officer might place greater emphasis upon social outcomes (e.g. equality) and the contribution to meeting social and economic needs or on its capacity to develop, while service 197users may place greater prominence on the quality of the service experience and the value they receive as individuals. Due to the complexity of values that any public sector user might seek to address, this is likely to require a delicate balance of responsibilities, often within budgetary constraints (Bason, 2018). Third, the challenge around appended forms of voluntary participation (e.g. such as consultation or surveys to evaluate services) remains in terms of professional opposition to user-led services and partial or cosmetic forms of participation. Structural changes administered under the former narratives have not been sufficient in overcoming these obstacles, suggesting that voluntary forms of participation are perhaps dependent upon a deeper cultural change, which seeks to alter the power imbalance (Baggott, 2005; Clark, 2007). This would involve re-conceptualising service users as knowledgeable, skilled and experienced players, through their integral role in service delivery, who can make important contributions through co-production and co-design. Finally, it is necessary that public service staff are trained appropriately in managing the service experience to create value. They are not currently trained to effectively deal with value creation in its various dimensions, apart from in terms of efficiency.

198References

Alford J. (2009), Engaging public sector clients: from service-delivery to co-production, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Baggott R. (2005), “A funny thing happened on the way to the forum ? reforming patient and public involvement in the NHS in England,” Public Administration, vol. 83, no 3, p. 533-551.

Bason C. (2018), Leading public sector innovation: co-creating for a better society, Bristol, Policy Press.

Callaghan G., Wistow G. (2006), “Publics, patients, citizens, consumers ? power and decision making in primary health care”, Public Administration, vol. 84, no 3, p. 583-601.

Chen C, Hubbard M., Liao C.-S. (2013), “When Public-Private Partnerships fail: analysing citizen engagement in Public-Private Partnerships-cases from Taiwan and China”, Public Management Review, vol. 15, no 6, p. 839-857.

Clark J. (2007), “Unsettled connections: citizens, consumers and the reform of public services,” Journal of Consumer Culture, vol. 7, no 2, p. 159-178.

European Commission (2008), “Think small first – a small business Act” for Europe, Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission (2015), Better regulation guidelines, Brussels, European Commission.

European Commission (2018), Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the re-use of public sector information, Brussels, European Commission.

European Commission (2019), eGovernment factsheets tenth anniversary report, Brussels, European Commission.

Gascó, M. (2017), “Living Labs: implementing open innovation in the public sector”, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 34, no 1, p. 90-98.

Jacobs L.R (2014), “The contested politics of public value”, Public Administration Review, 74.4 (2014), p. 480-494.

Meijer A. (2016), “Coproduction as a structural transformation of the public sector”, International Journal of Public Sector Management, 29.6 (2016), p. 596-611.

Mergel I. (2017), “Digital service teams: challenges and recommendations for Government”, Using Technology Series, IBM Center for the Business of Government.

199Meynhardt T. (2009), “Public value inside: what is public value creation ?”, International Journal of Public Administration, vol. 32, no 3, p. 192-219.

Oprea, N. (ed.) (2019), “Research Report on Experiments,” Co-VAL Deliverable 1.3.

Osborne S. P., Radnor Z., Kinder T. Vidal, I. (2015), “The SERVICE framework: a Public-Service-Dominant approach to sustainable public services,” British Journal of Management, vol. 26, no 3, p. 424-438.

Osborne S. P., Radnor Z., Nasi G. (2013), “A new theory for public service management? toward a (Public) Service-Dominant approach”, The American Review of Public Administration, vol. 43, no 2, p. 135-158.

Osborne S. P., Radnor Z., Strokosch K. (2016), “Co-production and the co-creation of value in public services: a suitable case for treatment ?”, Public Management Review, vol. 18, no 5, p. 639-653.

Pollitt C., Bouckaert G. (2004), Public management reform: a comparative analysis, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Rizzo F., Deserti A., Cobanli O. (2017), “Introducing design thinking in social innovation and in the public sector: a design based learning framework,” European Public and Social Innovation Review (EPSIR), vol. 2, no 1, p. 127-143.

Shaw R. (2013), “Another size fits all? public value management and challenges for institutional design,” Public Management Review, vol. 15, no 4, p. 477-500.

Skålén P., Karlsson J., Engen M., Magnusson P. (2018), “Understanding public service innovation as resource integration and creation of value propositions,” Australian Journal of Public Administration, vol. 77, no 4, p. 700-714.

Stickdorn M. (2010), “Five principles of service design thinking”, in Schneider J., Stickdorn M., Bisset F., Andrews K., Lawrence A. (eds.), This is Service Design Thinking: Basics, Tools, Cases, Amsterdam: BIS.

Terry Larry D. (1993), “Why we should abandon the misconceived quest to reconcile public entrepreneurship with democracy”, Public Administration Review, vol. 53, no 4, p. 393-395

Tinholt D., van der Linden N., Enzerink S., Geillei R., Groeneveld A., Cattaneo G., Aguzzi S., Pallaro F.; Noci G., Benedetti M., Marchio G., Salvadori A. (2018), eGovernment benchmark 2018, Brussels, European Union.

Trischler J., Scott D. R. (2016), “Designing public services: the usefulness of three service design methods for identifying user experiences”, Public Management Review, vol. 18, no 5, p. 718-739.

Vigoda E. (2002), “From responsiveness to collaboration: governance, citizens, and the next generation of public administration”, Public Administration Review, vol. 62, no 5, p. 527-540.

200Voorberg W., Bekkers V., Tummers L. (2015), “A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: embarking on the social innovation journey”, Public Management Review, vol. 17, no 9, p. 1333-1357.

Voorberg W., Jilke S., Tummers L., Bekkers V. (2018), “Financial rewards do not stimulate coproduction: evidence from two experiments”, Public Administration Review, vol. 78, no 6, p. 864-873.

Yasuoka M., Akasaka F., Kimura A., Ihara M. (2018), “Living Labs as a methodology for service design: an analysis based on cases and discussions from a systems approach point of view”, International Design Conference Paper: Design 2018.

1 Corresponding author: francesco.mureddu@lisboncouncil.net. Francesco Mureddu is director at The Lisbon Council. David Osimo is director of research at The Lisbon Council. The paper draws on research conducted by the 12-member Co-VAL consortium, co-funded by the European Union. The opinions expressed in this interactive policy brief are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Lisbon Council, the European Commission, the Co-VAL consortium members or any of their associates.

2 Eurostat, Individuals Using the Internet for Interaction with Public Authorities by Type of Interaction, 13 March 2019 update.

3 Ibid.

4 Council of the European Union and European Economic Area, The 2017 Tallinn Ministerial Declaration on eGovernment, 6 October 2017.

5 Openbilanci is developed by Openpolis.it, an Italian nongovernmental organisation.

6 For more on ENoLL, visit https://enoll.org/about-us.

7 Alexis C. Madrigal, “When the Nerds Go Marching In,” The Atlantic, 16 November 2012.

8 Most of the pioneering initiatives and think tanks for design thinking in public services come from Scandinavia, such as Mindlab in Denmark and Demos Helsinki in Finland. Norway is considered the most advanced country for adoption of service design in the public sector. See Birgit Mager, Service Design Impact Report: Public Sector (Cologne: Service Design Network, 2016).

9 The two experiments carried out by Co-VAL required participants to perform administrative tasks for two philanthropic activities related to health. The results showed that citizens who receive information directly from a beneficiary are more willing to co-produce, while monetary reward alone has no impact on influencing citizens in the production process.

10 Several national and local government have already started to report their co-creation activity. Visit http://www.co-val.eu/dashboard/for more.