Les nouveaux services d’intermédiation Les plateformes collaboratives pair-à-pair dans les services hôteliers

- Type de publication : Article de revue

- Revue : European Review of Service Economics and Management Revue européenne d’économie et management des services

2019 – 2, n° 8. varia - Auteurs : Bertrand (Daisy), Léo (Pierre-Yves), Philippe (Jean)

- Résumé : Internet a permis l’émergence d’un nouveau type d’entreprises qui ne fournissent plus elles-mêmes les services qui leur sont demandés, mais connectent les consommateurs à des particuliers-fournisseurs afin qu’ils répondent à leurs besoins. Cette étude menée sur 47 plateformes d’hébergement collaboratif actives en France, porte sur les services réellement fournis par ces plateformes et la manière dont elles parviennent à maîtriser la qualité de service fournie par des particuliers.

- Pages : 17 à 53

- Revue : Revue Européenne d’Économie et Management des Services

- Thème CLIL : 3306 -- SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES -- Économie de la mondialisation et du développement

- EAN : 9782406098621

- ISBN : 978-2-406-09862-1

- ISSN : 2555-0284

- DOI : 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-09862-1.p.0017

- Éditeur : Classiques Garnier

- Mise en ligne : 09/12/2019

- Périodicité : Semestrielle

- Langue : Anglais

- Mots-clés : Services, hébergement de tourisme, économie collaborative, pair-à-pair, plateformes collaboratives, netnographie

The new go-between services

Peer-to-peer sharing platforms in hospitality services

Daisy Bertrand1

Pierre-Yves Léo

Jean Philippe

Aix Marseille Université,

Université de Toulon, CERGAM, Aix-en-Provence, France

Introduction

Over the last decade, a new type of service has emerged on the Internet: services offered by companies (commonly referred to as platforms or sharing platforms) that connect individuals providing services with other individuals who consume those services. After a period of breath-taking growth, these collaborative services have entered a phase of maturity marked by consolidation and restructuring, at least in some sectors.

In the accommodation sector,the leading platform, Airbnb, is no longer restricted to private apartments or villas and now markets overnight stays at hotels. Today, Airbnb also offers to combine “experiences” and will soon offer flights. In France, Airbnb has opened a call centre to assist French customers in their own language. Airbnb has thus transcended its status as a purely electronic company to assume responsibilities for the realities of accommodation (problems with keys, water heaters, cleanliness, etc.).

18Other actors in the accommodation sector are competing with Airbnb. In France, Gîtes de France (70,000 homes from more than 42,000 owners of homes and guest houses) and Clévacances (nearly 20,000 homes in France and 1,500 overseas) have decided to create a common platform while maintaining both brands and the privileged relationships they have built with the owners. Leboncoin, another leading advertising platform, is now entering the accommodation business. Hotel companies have not been left out. Accor Group has moved beyond its historical scope in the hotel business and has taken over Onefinestay, a sharing platform specializing in luxury residences. Accor also sells package tours (journeys + hotel) on accorhotels.com in partnership with Misterfly. These are just a few of the examples that can be cited; the major players in the accommodation business seem unable to remain in their traditional market and are making bold bets to capture tourist flows.

Nevertheless, Bertrand et al. (2017) shows that despite their success, so-called sharing platforms, especially hosting services, are experiencing quality problems. Recently, the European Commission sent Airbnb a formal notice that it must modify its terms of service: surcharges such as service and cleaning fees should be announced at the beginning of the reservation process; the content of the company’s offers should be more clearly specified; and it should be clear whether the offer comes from a professional or an individual. Sharing platforms are thus facing traditional problems encountered by service companies.

The sharing economy has grown due to the new management capabilities offered by Internet platform tools. Platforms are defined by Rochet and Tirole (2003) as products, services, companies or institutions that act as intermediaries between two or more groups of agents. Their emergence is a phenomenon that now impacts most activities, whether they involve material goods or services. On the Internet, the role of a platform is to connect individuals or institutions based on their requests and offers. Annabelle Gawer (2009) describes a platform as a founding block from which a multitude of firms can develop complementary products, technologies and services. The companies in the periphery of the founding centre constitute the collaborative ecosystem of the platform.

Platforms are present in many service fields. They usually support a service, but whereas some platforms connect professional providers and consumers, others organize services between individuals. This is not 19a simple extension of the e-commerce model but a whole new service context that calls into question many achievements of service marketing and management. Internet platforms have broken the constraints related to proximity or to the necessary reciprocal acquaintances that governed exchanges between individuals and exchanges between economic agents. This has allowed individuals to offer other people goods or services for which they do not have a permanent use.

Prices are generally below-market because of the conjunction of two phenomena: most individuals underestimate the cost of their own work when it is done in addition to their main activity; they also systematically underestimate the capital cost of the goods (cars, household goods, tools) that they make available to other individuals. Indeed, current lifestyles often lead people to own multiple cars, equipment or even residences (Ellen, 2015). These facilities are chronically underutilized, a phenomenon accentuated by the downtrend in household size in developed countries. Over-equipment also leads households to systematically underestimate the cost of use and depreciation of their equipment. Sharing platforms enable a timely and easy valuation of these unused capacities by putting the suppliers in contact with interested consumers.

Since 2008, the sharing economy and peer-to-peer platforms have developed in the economic context of the post-crisis period. This context resulted not only in a reduction of household purchasing power but also in the emergence of sober consumption practices and the search for different lifestyles. The sharing economy drastically decreases the cost of access to consumption and allows a new class of consumers to emerge. According to Rifkin (2014), these “prosumers” (consumers who are also contributing producers) are organizing to finance their purchases, at least in part, by the productive exploitation of their property or skills. Empirical studies of the motivations of collaborative consumers show that the search for low prices (or economic benefits) is an important driver (Hamari et al., 2016; Pipame, 2015; Guttentag, 2018; Quinby and Gasdia, 2014), sometimes even the most important one (Bertrand et al., 2017; Nowak et al., 2015; Tussyadiah, 2015). However, other motivations coexist, such as ecology, the need for social links and the search for new experiences.

Beyond the price paid, consumers of peer-to-peer services also often highlight the quality of the exchanges and the user-friendliness of the 20delivery, dimensions that would have been lost, according to them, by traditional service providers despite their quality. The sharing economy re-raises old questions about the interaction and exchange between consumers and service providers. Experiential marketing (Carù and Cova, 2006) has analysed the need for hedonistic gratification, sensations and emotions that consumers are seeking in Western societies today. More than the products themselves, the experience they provide and their meaning are valued. This quest not only responds to needs but also helps the consumer shape her/his identity (Cova and Cova, 2001). Peer-to-peer services offer new consumer contexts, creating experiences that can be surprising and that unfold according to the four phases of experiential marketing: anticipation through online applications, the purchase, the experience itself and the memory of the experience during the evaluation that follows.

The typology of services proposed by Lovelock (2000) crosses the recipient of the service (people, objects and organizations) with the type of market in which the service is offered: mass consumption (B to C) or industrial (B to B). The emergence of sharing platforms reveals a new category of consumer markets: consumer to consumer (C to C), or if we adopt a formulation that seems more appropriate, individual to individual or peer-to-peer (P to P), terms that are now in common parlance. The analysis of B to C services has helped forge the basic concepts of service management; and analysis of services from individual to individual managed by the platforms shows that they are not different in nature but have specific characteristics that must be analysed. Research on the management and marketing of services has made it possible to clearly identify each service and to propose rules for the efficient management of these activities, but they remain focused on a single service and a single provider even though complex forms of activity involving several service providers have become increasingly common.

The concept of a sharing platform is justified in the sense that individuals create value by exchanging with each other (Terrasse, 2016). The proposal for goods or services is made by an individual, and the transaction is finalized and evaluated between users; originally the platform only offered support services that brought together matching needs and offers. At the very heart of this concept, platform architecture faces a dual market: that of the individual suppliers and that of the consumers. 21The platform incurs costs to serve each of these user groups, but it can also potentially generate revenue from each group. Eisenmann et al. (2006), studying dual market network platforms, concluded that such platforms need to rapidly create a network effect. They suggest first subsidizing the private suppliers and then subsidizing the private users to encourage adoption by both. Accordingly, it would be necessary to realize rapid growth in the number of hosted transactions to reach the volume of transactions corresponding to the break-even point.

Sharing platforms can implement a whole set of services (e.g., display of offers, prices and requests, messaging services, secured payments). Additional pricing can be justified by more elaborate services (e.g., insurance, options for highlighting and referencing the classified ads, trusted third parties…). According to Baranger et al. (2016), the emergence of sharing practices and more generally, the digitization of service activities, will lead to a hybridization of service business models in two directions simultaneously: minimalist strategies attributable to the automation of simple tasks and strategies enriching the offer of services through advice and expertise.

The question of customer loyalty poses difficulties because the services delivered via sharing platforms cannot be formatted, unlike those offered by an integrated firm or franchisees applying a network policy. Quality management on sharing platforms is based on a system of post-experiment cross-evaluations that can be either spontaneous or requested from the users. This system is intended to reduce the risk perceived by individuals and to lead to virtuous behaviour by both individual providers and users, but the reality can be quite different.

Sharing platforms offering peer-to-peer services are therefore at the crossroads of several issues: social change, consumption patterns change, new consumer service organizations, and new rules for service management. Many research questions arise such as the following: How do sharing platforms deal with quality problems attributable to the heterogeneity of offers? Which services are offered by sharing platforms? Can a typology be deduced? How do sharing platforms manage relationships with their customers?

This paper proposes certain elements that are likely to reveal the answers to these questions. More precisely, our research analyses the consumption of accommodation services primarily from the point of 22view of the supply and management of services offered by the platforms. After a short review of the literature, we clarify the boundaries of our research field and provide information about the methods used to collect and analyse the data. In the second section, we provide a brief overview of the 47 peer-to-peer hosting platforms operating in France in June 2018. Our objective is to determine which services are offered by the different platforms and to identify types of organizations. Based on a netnography, in the third part, we present the characteristics of the customer relationship management of peer-to-peer hosting platforms compared to that of traditional hospitality firms. Testimonials from consumers enable us to highlight platforms’ organizational choices and the difficulties entailed by their customer relationship system.

1. Delimitation of the phenomenon

To provide some answers to these questions, we first circumscribe the relatively new and moving object of study that interests us. We will then propose some conceptual elements that enable us to better understand how far this new context will entail changes for service management. Finally, we will present the methods used to produce the results presented below.

1.1 Sharing economy: clarification

of a fuzzy concept and operational delimitation

The term “collaborative consumption” appeared in the United States with Felson and Spaeth (1978), who defined it as “events during which one or more people consume goods or services in order to share an activity with others”.

The rapid development of the Internet and the emergence of Web 2.0 have greatly facilitated contacts and direct exchanges between individuals (peers) and put the term “collaborative consumption” back in the spotlight, but in a different scope. In some areas, these new exchanges between peers are taking place on an unprecedented scale, which can be perceived as a threat by professionals in the field. The interest in these sharing activities is reflected not only in the number of articles published in the media, 23the press and on the Internet (Martin, 2016) but also by the increasing number of academic papers that have been published: in 2006, only 83 were referenced on Google Scholar, whereas in 2016, 7620 were referenced (Alcantara Guimaraes et al., 2018). Most of these papers used the words “sharing economy” to refer to peer-to-peer activities (Martin, 2016; Alcantara Guimaraes et al., 2018). However, many other terms are also used to refer to these activities, either as synonyms or to relate to distinct concepts. Thus, as emphasized by Codagnone and Martens (2016), the activities and organizations that are commonly referred to as the sharing economy have also been labelled “collaborative consumption” (Botsman, 2013; Botsman and Rogers, 2010a and 2010b), “access-based consumption” (Bardhi and Eckhardt, 2012; Belk, 2014a), “connected consumption” (Dubois et al., 2014; Schor, 2014; Schor and Fitzmaurice, 2015) and even the “shared economy”, “collaborative economy” (e.g., Dredge and Gyimothy, 2015; Stokes et al., 2014) or “peer economy” (Bellotti et al., 2015).

Many studies (Bardhi and Eckhardt, 2012; Botsman, 2013; Ranchordas, 2015; see Guyader, 2018 for an overview) have attempted to define these terms, but they have not yet reached consensual definitions. According to Codagnone and Martens (2016), some of these definitions are intentional, providing clear definitions and sufficient conditions to delimit the perimeter of the concepts, but the overwhelming majority of the available definitions are more pragmatic based on few key features and exemplification.

As for the activities concerned, noshared consensus on what activities are included in the sharing economy exists (Codagnone and Martens, 2016): “the sharing economy lacks a shared definition” (Botsman, 2013). Indeed, the concept of sharing economy covers today very diverse realities. Codagnone et al. (2016, p. 22) summarize the situation as follows: the sharing economy is “commonly used to indicate a wide range of digital commercial or non-profit platforms facilitating exchanges amongst a variety of players through a variety of interaction modalities (P2P, P2B, B2P, B2B, G2G) that all broadly enable consumption or productive activities leveraging capital assets (money, real estate property, equipment, cars, etc.) goods, skills, or just time”. Depending on the authors, the voluntary (not-for-profit) sector can be linked not only to the entire social and solidarity economy but also to highly lucrative activities. Moreover, some authors include only peer-to-peer transactions, while others do not exclude B2C, G2C or even B2B and G2G transactions.

24In 2013, Botsman defined the sharing economy as “an economic model based on sharing underutilized assets from spaces to skills to stuff for monetary or non-monetary benefits. It is currently largely talked about in relation to P2P marketplaces but equal opportunity lies in the B2C models”. Collaborative consumption is defined as “an economic model based on sharing, swapping, trading, or renting products and services, enabling access over ownership” (Botsman, 2013). This collaborative consumption is one of the four components of the collaborative economy “built on distributed networks of connected individuals and communities versus centralized institutions, transforming how we produce, consume, finance, and learn”. This author favours a very broad societal point of view that results in the inclusion of extremely heterogeneous actors and activities.

Other authors have tried to provide a more detailed definition of the contemporary sharing phenomenon. Bardhi and Eckhart (2012) focus on consumer preference for use rather than ownership. However, this definition applies equally to the entire traditional rental market and even to services in general. According to Belk (2014b), collaborative consumption involves people coordinating the acquisition and the distribution of a resource (time, skill, or objects) for a fee or non-monetary compensation. This definition therefore includes activities such as sale, lease, bartering and swapping but excludes volunteering, lending or giving, which is at the heart of what some people call “collaborative peer-to-peer” as opposed to “merchant peer-to-peer”. This “collaborative peer-to-peer” is still different from what Belk (2014a) calls “true sharing”, in which the emphasis is put on temporary access rather than ownership with the absence of compensation but the intermediation of an Internet platform.

Thus, not all authors agree on the boundaries of what should be called the sharing economy or collaborative consumption and, of course, the choice of a perimeter depends on which issue is treated. The official definition of the sharing economy on the website of the French Directorate of Legal and Administrative Information (Dila, 2016) corresponds fairly well to the field we delimited based on our research questions:

The collaborative economy is a peer-to-peer economy. It is based on the sharing or exchange between individuals of goods, services, or knowledge, with monetary exchange or without monetary exchange, through a digital platform for linking.

25To us, two criteria seem essential to determine which companies (or platforms) can enter our field of analysis:

–They must operate on the Internet, particularly through the use of a platform whose services may or may not be remunerated. This criterion leads to exclude from our scope all traditional sharing activities that do not include online intermediation such as garage sales or exchanges of services between neighbours.

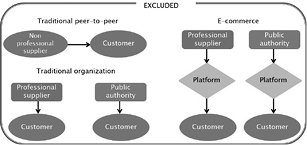

–They must organize and facilitate the linking of two individuals for a transaction, one as a supplier (producer, seller or service provider) acting on a non-professional basis and the other as a consumer (user, beneficiary or buyer), also acting on a non-professional basis. Platforms act only as intermediaries and never completely substitute for one of the individuals during either the selection of a supplier by a consumer or the realization of the transaction. As illustrated in Figure 1, this criterion leads to exclude from our scope of analysis all transactions other than C2C or P2P, namely, P2B, B2C, B2B, G2C, G2G and all e-commerce activities.

Fig. 1 – Boundaries of the sharing peer-to-peer activity.

26Two other criteria will be added: a national or an international impact criterion to avoid all tiny, purely local platforms and, in the context of this research, a sectoral criterion: only the specialized platforms of the accommodation sector will be taken into account.

However, using these criteria still defines a rather heterogenous field of investigation, as it gathers platforms that are very different from one another. To obtain a better representation of the field, authors attempt to classify these platforms according to their characteristics and to make typologies. Numerous classification criteria are available and different insights are provided depending on which ones are taken into account. The simplest approach is certainly to classify the platforms according to their sector of activity (Pipame, 2015; Bertrand et al., 2017) or their size (number of ads or number of members). Another approach, based on the users’ point of view, considers the type of transactions they organize between peers (Bertrand et al., 2017; Pipame, 2015; Petrini et al., 2017). Terms of exchange between peers can be classified not only according to whether or not they imply a transfer of ownership but also according to the required counterpart (none, financial or other). Crossing these two criteria leads to 6 types of transactions: donation, bartering and selling on one side, lending, exchanging and renting on the other. It is also possible to categorize platforms based on their own commercial orientation: their intermediation services can be provided for free or for a fee (Bertrand et al., 2017; Bertrand, Aldebert and Léo, 2018; Bertrand, Léo and Philippe, 2018; Codagnone et al., 2016; Petrini et al., 2017). This additional criterion makes it possible to identify 4 situations. Some platforms (e.g., Leboncoin, OuLoger) offer completely free services to their users and simply link offers and requests. Other sites (e.g., Airbnb, Homelidays) add their remuneration to the price agreed to between the peers. A third category (e.g., Servas, Home for Home) proposes paid intermediation services, although transactions between peers are free of charge. Finally, some sites are clearly non-commercial and promote exchanges based on free transactions (e.g., Couchsurfing).

The players involved (P2P, B2C or G2C) shed further light on this heterogeneous field. Platforms can be ordered along a continuum representing the proportion of private providers hosted. In theory, this continuum varies from 100 % of private providers in the case of exclusively P2P platforms to the extreme case of 100 % of professional 27providers in the case of e-commerce platforms (B2C). Combining profit orientation and interaction modality, Codagnone et al. (2016) identify three main groups of platforms: true sharing platforms that are not-for-profit and exclusively peer-to-peer; commercial B2P, B2B and G2G platforms; and commercial P2P platforms. In another attempt, the same authors combine interaction modalities and asset mix to identify 4 groups of platforms: asset-intensive provision of goods and services to peers, labour-intensive services to peers through unskilled manual work, labour-intensive services to businesses, and asset-intensive goods and services to businesses. However, this typology into 4 groups is not satisfactory because it does not fully understand the reality, and hybridization areas are necessary. Among many others (Albarède, 2015), two criteria are of particular interest for our purposes: which services are offered by the platform and the extent to which the platform is involved in the exchange between peers (Bertrand et al., 2017; Bertrand, Léo and Philippe, 2018). Once again, platforms can be ordered along a continuum with 5 milestones. Platforms located on one side of this continuum are merely classified advertisement sites such as Leboncoin, with minimal involvement in the relationship between peers. The three intermediate milestones are ad sites offering back-up services; then sites acting as marketplaces, acting as trusted third parties; and finally, sites that add other services, whether in an optional or in a mandatory way. The more these additional services are developed, the more the platform tends to interfere in the relationship it organizes between the individuals. At the end of this continuum, platforms are no longer different from commercial agencies because they act under the mandate of the individual supplier and seek its exclusivity. Therefore, such platforms’ boundaries with more traditional e-commerce firms appear rather fuzzy, and a grey zone is fed by numerous movements: the professionalization of private suppliers, opening peer-to-peer transactions of classic e-commerce platforms that wish to participate in this new dynamic, sharing platforms accepting professional suppliers, and the evolution of some sharing platforms towards increased control of the offers and the relationships that they organize between suppliers and consumers, leading them to behave (more or less) like pure commercial agencies. In this grey area, it is difficult to say whether a platform comes out of the sharing economy or the more classical economy of e-commerce or agencies.

281.2 Steps towards a conceptualization

of sharing platforms services

The definition of services has always been a subject of theoretical debate. Indeed, if it is quite easy to experience a specific service, and it is far more difficult to provide a definition because of the heterogeneity of the field to be encompassed. Researchers have attempted to systematically describe the elements constituting a service and how it is delivered. Several service models have been proposed, including the “service delivery system” and the French “servuction”. All of these models highlight that all service activities have an important element: the border between what can be seen by the customer (the staff in contact, the material support) and the rest of the service organization, namely, the back office. This border was called the “line of visibility” by Shostack (1992) because it allows the customer to see the organization’s material support and to interact with the staff.

Modelizing the services offered by peer-to-peer platforms is more complex. First, the line of visibility becomes a virtual one: service delivery and service evidence are only obtained by Web pages. Indeed, there is no front-line contact staff: it is the back office, or more precisely, the platform’s algorithm that interacts directly with the customer. Indeed, two kind of services are intimately mixed: on the one hand, the platform’s own service consists of gathering information from potential customers and potential suppliers and then processing this information to propose solutions for both parties. On the other hand, the supplier and the customer meet for a specific service, which is completely different from the linking process performed by the platform. The platform’s role is to help match customers’ demands with available offers by delivering information about the services offered by suppliers. It also defines the rules that both should observe when interacting. However, the customer is not fully aware of the duality of the service she/he acquires. According to Baranger et al. (2016), platforms obliterate the front office for the benefit of the back office, and doing so favours formatted answers to requested information. In traditional services, the line of visibility can be used as a marketing tool: by moving this line, the service firm can expand or reduce its service evidence. Making some parts of the organization visible (or invisible) to the customer can profoundly modify the atmosphere in service interactions and change the customer’s trust 29in the service firm. In platform services, the line of visibility is located much closer in the organization. Requests and demands are answered more rapidly, but the customer does not have access to all the data owned by the platform about her/himself or about the offers that are proposed. Therefore, the virtual visibility line cannot play a significant role in how customers trust a platform.

Furthermore, sharing platforms call in question one of the main concepts in service management: service quality management. Service quality is evaluated through customers’ post-experience satisfaction, which is analysed by questioning them about their most recent experience and asking them to assess and compare key service elements with reference standards. Many quality measuring scales have been developed in an attempt to eliminate answering bias. One compulsory condition is that the questionnaire should be answered shortly after the service experience. The digitalized services delivered by the platforms introduce new issues in this field compared with traditional service delivery:

–The customers, whether suppliers or buyers, are much more involved in the service delivery. Indeed, they must provide much more information about themselves, about what they are looking for, or about the service they offer to provide.

–This information is not limited to sharing platforms but extends to many Internet communication tools such as forums, specialized websites and ratings posted by Internet users.

–Service rating is almost simultaneous with the experience; it can even be a continuous process during delivery. Theoretically, this should allow the platform to better adjust the delivered service to the consumer’s requirements. However, (as we will show later in this paper), this adjustment often remains problematic.

–According to the disconfirmation model (Oliver, 1981), regardless of the service involved, customer satisfaction is always based on a comparison of what was experienced with what was expected. However, sharing platforms do largely create expectations and service antecedents through the manner in which they choose to present the proposed services. Today, hosting peer-to-peer platforms display the full scenery around the rental accommodation offered: they implement actions so that the housing is presented 30–at its best angles, give advice to the hosts (about their pictures, the presentation of their home) and recommend providers such as photographers to stage the house and give it a positive image to attract future customers.

–Recommendation takes precedence over customer satisfaction for platform management. Indeed, the value of a platform depends on its listings and the number of customers. The more ads published, the more the platform attracts new ads and the more potential consumers visit the website (Constantiou et al., 2017). In this way, the platform will expand its intermediary role and become increasingly profitable as a result of the very low marginal costs for new ads or transactions.

Finally, the manner in which the service firm has knowledge about its customers and organizes customer relationships is also different when using peer-to-peer platforms. Traditional service firms seek information on customers to better understand their needs and expectations. This allows them to treat customers differently according to their profile: some customers belongs to the main marketing demographic from which turnover and profit must be earned, while others are considered additional customers, favouring a greater rate of use of equipment or productive capacities. Baranger et al. (2016) identify what they call hyper-relational marketing in how peer-to-peer platforms tend to tie relationships with their customers: a considerable quantity of personal information is gathered on each user (customer or provider) with (or without) her/his agreement with the goal of continuously presenting her/him offers that meet his/her personal needs or interests. Consumers are no longer gathered into strategic groups because the platform fees are generally the same for each transaction the platforms helps to organize. Consequently, most platforms aim for multiple repeat buying and mass consumption more than high-value sales. For hosting services this means a huge number of ads located in various places around the world.

1.3 Method

After clarifying how the census of the platforms was conducted, we will present the method used to collect and analyse comments left on the Internet by the consumers of peer-to-peer platforms and traditional hotels.

311.3.1 Census of platforms

This study is based on research (Bertrand et al., 2017) that aimed to identify and study all the sharing platforms operating in France in 8 consumer sectors: food (food surplus sharing, food production via gardening), second-hand household goods and equipment, second-hand clothing and accessories, housing, hospitality, food and beverage services (peer-to-peer dining websites, take-away), mobility and transport (ride-sharing, peer-to-peer car rental, parking spaces) and jobbing (pet sitting, baby-sitting, household services). To be as exhaustive as possible, systematic research was conducted for 3 months between late 2016 and early 2017 using Internet search engines, research reports (Pipame, 2015; Terrasse, 2016), economic news sites (Les Échos, Le Figaro, La Tribune, Capital, BFM-business) and sites dedicated to start-ups (e.g., myfrenchstartup, presse-citron, alloweb, jaimelesstartups). Among the information sought, sites discussing other competing or complementary platforms were valuable because they allowed for the initiation of a “snowball” search process that made it possible to achieve relatively complete coverage of the field to be investigated.

The tourist accommodation sector was updated in June 2018 to identify new platforms that had emerged and to eliminate those that had ceased their activity. A systematic survey of information was also conducted to count the number of online ads, noting how platforms worked and which services they offered. Finally, traffic statistics for each site measured by the number of visits recorded over a given period were also collected via SimilarWeb. These data made it possible to quickly identify the level of activity of a platform or to detect if a site was no longer active. At the end of this process, 47 platforms offering holiday accommodation were identified (details given in appendix).

1.3.2 The consumer’s opinion

To study consumer opinion regarding the peer-to-peer hosting offer, netnography was employed. This qualitative technique, initially proposed by Kozinets (1998, 2002), is a non-intrusive ethnographic approach adapted to the study of online communities. In our case, it consisted in collecting and exploiting the content of messages posted 32by consumers of both traditional and the peer-to-peer hosting services on dedicated forums over an a priori defined period (January 1 to July 1, 2017).

Among all the available opinions, only those posted by consumers after an actual experience were retained. Accordingly, we primarily sought opinions from sites specializing in the collection of customer reviews (Avis-vérifiés, Feefo, Trustpilot, Custplace, TripAdvisor, Satizfaction) or cashback sites (Igraal, Ebuyclub, Poulpéo), and only a few were collected from sources such as news (L’internaute, Facebook) or other sites (Mon avis, Que choisir, Le Routard, 60 millions de consommateurs). The collection yielded 298 comments from collaborative users (166 of which expressed a mixed or negative opinion and 132 of which expressed a positive opinion) and 498 comments from hotel users (227 of which expressed a mixed or negative opinion and 271 of which expressed a positive opinion).

The collected material was subject to a content analysis from an inductive perspective to identify categories of analysis, as advised by Spiggle (1994). These categories were then grouped by themes and then by major themes. Finally, coding was conducted to correctly analyse each theme according to the valence (positive or negative) that the consumer expressed about each of the subjects she/he addressed.

Like all netnography, the method we have adopted has a bias that is related to how the information is collected: the Internet is a natural outlet for disappointment, frustration or anger. These feelings are real, but their proportion is certainly amplified compared to daily reality. Accordingly, the image provided is naturally very contrasted or even caricatured. However, this distorting mirror function makes it possible to warn about malfunctions that are statistically infrequent but that may have serious consequences in the long term. This is also a way for businesses to better understand what is important to customers and what they cannot tolerate. This tool therefore makes it possible to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of this new peer-to-peer consumption mode compared to what is expressed by users of professional hosting solutions.

332. The services offered by hosting platforms:

a lever of differentiation

Before analysing the service offered by hosting peer-to-peer platforms, we will provide an overview of their characteristics in terms of their origin, size, type of transaction and revenue source.

2.1 Platforms and their characteristics

Despite our limitation to the hosting sector, the platforms we have identified are very heterogeneous in terms of their origin, size, attendance and mode of operation.

Half of the 47 accommodation peer-to-peer platforms listed are located in France, and the others are mainly European (7 British, 3 German, 3 Spanish, 3 Swiss, 1 Dutch); however, there are also 5 American platforms, one Canadian platform and one Australian platform.

In terms of size, the platforms range from fewer than 500 ads (4 platforms) to nearly 4.5 million ads on the leading Airbnb platform, with a median of approximately 12,300 ads. The range is also very open with regard to the traffic the platforms generate on the Internet: 19 are not referenced by SimilarWeb, which indicates low popularity, with less than 5000 quarterly visits. Beyond that, the number of “clicks” recorded ranges from 65,000 to 145 million, with a median of close to 330,000.

Platforms also differ according to their method of financing. Three modes have been highlighted: half of the platforms ask users to subscribe, including freemium systems in which a minimal service is offered for free, and numerous optional services are only available to subscribers. Approximately one-third of the platforms ask for a commission calculated on the amount of the transaction between individuals. Other sources of turnover are in use in approximately 11 % of the platforms; this includes sales of specific services, sales of additional products or sales of advertising space on the website. Finally, a few platforms (11 %) do not ask any payment from their users and do not mention any other source of revenue. These three modes of remuneration (subscription, commission, other sales) are not mutually exclusive, and all possible 34combinations can be observed. However, platforms mostly use a single mode (Bertrand, Aldebert and Léo, 2018).

From another point of view, platforms also differ according to the type of transaction set up between the individual provider and the consumer. Three types of transactions have been identified, namely, whether the housing is offered for free (lending), on the condition of an exchange (swapping), or for paid rental:

–In the lending model (e.g., Couchsurfing), guests are welcome in the hosts’ accommodation without any compensation; customers from all over the world meet via these specialized peer-to-peer platforms. The few sites (13 %) supporting this type of transaction focus on cultural exchange, sharing value and experience or more ideological aims such as increasing intercultural understanding and strengthening peace on our planet. Consistent with free transactions between peers, these platforms offer completely free services and are financed by other means. The number of these platforms is not negligible; they account for nearly 14 % of the total number of ads.

–When exchanging houses or apartments, hosts make their housing available to the community and in exchange, can stay in the home of another member of the community. Exchange can be either reciprocal or non-reciprocal. In the first case, a family comes to your home and in return you go to theirs either on the same dates or on different dates. To allow non-reciprocal swaps, many platforms have developed complex compensation systems, mostly based on a scoring system: you earn points when you lend your home and you can spend them to stay in another home. This type of quasi-monetary system gives more flexibility for exchanges while encouraging members loyalty. Thirty-four percent of the hosting platforms promote this type of home swapping. Transactions between peers are completely free, but most platforms (71 %) are remunerated by users via a subscription system.

–Rental is the most traditional and usual method: a host places his home or part of his home at the disposal of customers in exchange for a fee. Platforms specializing in this type of transaction are by far the most numerous (66 %). Nearly half of them charge a commission to the consumer, the supplier or both; most of the others 35–require a subscription. These platforms are strongly present on the market: they have 6 times more ads than the exchange platforms and the total Internet traffic they generate is 130 times denser. Admittedly, the weight of the leader Airbnb is a key factor in the gap between the two forms, but this difference remains important even if we remove Airbnb: there are twice as many ads on rental platforms and their traffic is 8 times denser.

Tab. 1 – Distribution of sharing hosting platforms according to their method

of financing and the form of relationships organized between individuals.

|

Subscription |

Commission |

Other |

Completely free use |

Together* |

|

|

Lending |

1 (%) |

- |

2 (33 %) |

3 (67 %) |

6 (13 %) |

|

Exchange |

12 (71 %) |

1 (6 %) |

1 (6 %) |

2 (18 %) |

16 (34 %) |

|

Rental |

13 (46 %) |

15 (54 %) |

2 (7 %) |

1 (4 %) |

31 (66 %) |

|

Together* |

24 (51 %) |

16 (34 %) |

5 (11 %) |

5 (11 %) |

47 (100 %) |

*Among the totals of rows or columns, some may slightly exceed the “together” figures because few platforms propose several modes of relation between individuals or have adopted several financing methods

2.2 What services are offered by the platforms?

To answer this question, we first give an overview of the services provided by the peer-to-peer hospitality platforms before describing each type of service.

2.2.1 General overview of peer-to-peer platforms’ services

Platforms do not own any accommodation; they are only intermediaries between a host and a guest. The central service of all hosting platforms is the connection between individuals providing accommodation and individuals seeking housing. Platforms provide a tool to describe the accommodation and the provider’s conditions for accepting a customer. Two services are intimately linked to this basic service, even if they are not provided by all platforms: an integrated messaging system and the ability for “guests” and hosts to post a comment once the hosting is complete. Beyond that, platforms offer many other services: either 36support services intended to facilitate the operations between individuals or with the platform, or “plus” services intended to enrich the value proposition. Finally, specific services are intended for the relationships that the platform wishes to maintain with its customers, guests or hosts. A customer service department is often in charge of these services, but such services can also be implemented independently of the platform. This decomposition into basic and complementary services shows that the platforms are part of this category of service that Djellal and Gallouj (2006) refer to as architectural services: their specificity requires consideration of all the services they aggregate to make a judgement about their strategic trajectory.

Tab. 2 – Services observed in 2018 on 47 peer-to-peer hosting platforms.

|

Services |

Observations |

Frequency |

|

Basic Services |

||

|

Integrated messaging system |

Exchanges between hosts and customers |

89 % |

|

Comments after hosting |

Post experience reciprocal evaluations |

65 % |

|

Direct contact with the host |

Exchanges between hosts and customers are possible before booking |

28 % |

|

Support services |

||

|

Online payment for hosts |

Support to pay for publication of ads |

59 % |

|

Online payment for customers |

Support to pay for the reservation |

40 % |

|

Identity verification |

Online verification: e-mail addresses, phone number, identity card |

36 % |

|

Travel insurance |

Optional |

30 % |

|

Guest insurance |

Optional |

28 % |

|

Security deposit |

Managed by the platform |

11 % |

|

Verified housing |

On the spot by a person mandated by the platform |

9 % |

|

Host recommendation |

By the platform, such as Airbnb superhosts |

4 % |

|

“Plus” Services |

||

|

Multi-site advertising |

Ads also published on partner sites |

19 % |

|

Experiences |

Activities for customers, sold separately |

15 % |

|

Services for business trips |

Administrative facilities, invoices |

11 % |

|

Housing for business trips |

Adapted for business customers |

9 % |

|

Services related to housing |

On-site doorkeeper, reception, cleaning, optional |

9 % |

|

Recommended addresses |

Restaurants, guides, language schools |

9 % |

|

Customer relationship services |

||

|

Social networks |

Platform accessible via social networks |

77 % |

|

Customer depart., phone access |

Phone number provided on the website |

66 % |

| 37

Customer depart., e-mail access |

Email address provided on the website |

62 % |

|

Customer depart., spoken languages |

Spoken languages other than the native language of the platform |

50 % |

|

Customer depart., integrated email messaging |

Accessible via an integrated messaging service |

38 % |

|

Customer depart., opening hours |

24/24 (34 %), office hours (11 %), non-specified (55 %) |

|

|

Customer depart., help |

Help with booking |

17 % |

|

Customer depart., mail address |

Mail address provided on the website |

9 % |

|

Host loyalty programme |

Exists |

9 % |

|

Customer loyalty programme |

Exists |

6 % |

|

Opinion on the platform |

User reviews on consumer review sites |

6 % |

|

Customer depart., urgency |

Planned emergency department |

4 % |

All of the services observed on the 47 accommodation platforms investigated are presented in Table 2. Of course, their categorization may be subject to discussion because the appropriate category may depend on the platform. Indeed, the same service can be considered central by one platform and a simple “plus” by another. In some cases, a support service can be seen as essential and therefore central or it can be optional and therefore simply constitute a “plus”. However, this classification has the merit of clarifying the abundance and the great diversity of the services offered.

2.2.2 Basic services

Most of the platforms provide an integrated messaging system that allows the customer to safely contact and communicate with a potential host. It is interesting to note that only a few platforms do not include this service: this is either a deliberate choice to prevent any direct communication between hosts and customers (as do Le Collectionist and Onefinestay, both platforms specializing in luxury residences) or a minimalist attitude that leaves customers completely free to contact potential hosts outside the platform via an email address or phone number included in the ad (3 platforms). Despite the availability of an integrated messaging system, ten platforms also allow the customer to contact a potential host directly before making a reservation. These platforms operate by subscriptions, the sale of services or advertising space, never by commission. It is easy to understand that they do not 38want to be bypassed by individuals. However, for both the customer and the host, the ability to communicate by telephone before booking could represent a real advantage, preventing misunderstandings and disappointments.

Platforms that do not provide any system for customers to describe and assess their experience are more numerous: 16 platforms from all categories (donation, exchange, rental, operating by subscription, commission, sale of services or advertising space or without a declared financial source) are in this category. Their only common point seems to lie in their modest size: on average, they display only 70,000 ads versus more than 300,000 for the 31 other platforms. The absence of any system of cross-evaluation deprives them of a system that is intended to moderate quality problems and reassure future customers. Comments, which are visible on the corresponding ad, make it possible to get an idea of the quality of the rental (accommodation, host…). Of course, this is not useful for Le Collectionist and Onefinestay because they control the quality of the luxury homes they are renting.

2.2.3 Transaction support services

Six types of transaction support services have been identified. A large number of platforms offer secured on-line payment tools that make it easy for hosts to pay for their subscription and any optional services and for customers to pay for the rental through the platform. In the latter case, this amount is generally kept by the platform until the day after the customer enters the accommodation. This intermediation reduces, without completely eliminating, the risk taken when one reserves with an individual provider. Indeed, this system has a double advantage: it guarantees the host against non-payment and the customer against fraudulent hosts (e.g., non-existent housing, housing not in conformity with the description): a simple complaint to the platform’s customer department will block the payment. The platform thus appears as a trusted third party, a generator of mutual trust.

Support services also help reduce the risks inherent in any transaction between two virtual unknowns (identity verification seems elementary) but can reassure users and may deter novice scammers; on the other hand, “honest” people may perceive inquisitorial or even vexatious control. 39This could partially explain why nearly two-thirds of the studied platforms do not perform this check. Another way to reduce the risks taken by hosts or customers is to add dedicated insurance to their offerings even if such insurance rarely covers all the risks that may arise. For the hosts, this insurance is often included in the conditions related to the registration of the accommodation offer, while for the customers, it is usually an optional extra.

Very few platforms offer other support services: 5 platforms manage security deposits which can secure the good behaviour of the customers (Le Collectionist, Onefinestay, Airbnb, Housetrip, Guesttoguest), 4 platforms organize an effective on-site housing verification service (Airbnb, Le Collectionist, Onefinestay and Wimdu) and 2 (Airbnb and Housetrip) have established a system for labelling hosts who regularly behave in accordance with the best practices recommended by the platform. These services have apparently been added to differentiate these platforms from potential competitors.

2.2.4 The “plus” services

Services that can be described as a “plus” are generally less often implemented by the accommodation platforms. Nine platforms run ads on multiple sites, usually on peer-to-peer platforms operating outside France, increasing the host’s chances of finding customers. This kind of service supposes that partnerships made with other platforms will homogenize the rules of presentation and intervention. One would think that only small platforms would use this service to access a larger network, but that is not completely the case, since some “big” platforms (Abritel, Amivac, Homelidays, Housetrip and MediaVacances) also propose this extra service.

Among the “plus” services, one can find “experiences”, namely, various activities offered either by individuals (such as Airbnb experiences) or by professionals (Onefinestay). Seven platforms market experiences in parallel with rentals to complete and enhance the rental experience: for example, Airbnb and MisterB&B host ads for, inter alia, guided tours, culinary discoveries, dance classes, and sports; Bedycasa promotes tours with homestays; and Le Collectionist and Onefinestay offer to organize or book customizable activities. Two platforms working on home lending 40(Couchsurfing and Servas) focus on activities that help customers meet others, and they even organize social events for their members.

The other “plus” services are offered by only a very small number of platforms. Some services are dedicated to professional customers: 5 platforms offer administrative services, 4 promote a selection of accommodations adapted to specific needs (schedules, location, equipment, connection) and 4 offer useful address guides so that customers can better enjoy their stay. A small number of platforms (4) have also set up optional services related to housing such as reception, a doorkeeper, cleaning and maintenance, etc. It is not surprising to find that these platforms include Airbnb, MisterB&B, Le Collectionist and Onefinestay. This is the ecosystem that can allow a platform to flourish because these services are quite helpful both to customers and to hosts, whose worries are alleviated by the services. For now, they remain “plus” services implemented by leading platforms in their niche.

2.2.5 Services for the customer relationship

An analysis of user comments posted on the Internet (Bertrand et al., 2017) highlighted that the client relationship was one of the main weaknesses of peer-to-peer hosting platforms. Therefore, services that have a marked customer orientation are particularly interesting to observe. First, we note that the majority (77 %) of platforms are present on social networks (4 different networks on average, but sometimes 7 or 8 networks), and this certainly contributes to facilitating customer relations.

All of the platforms mention the existence of a customer service department, but the functions and the accessibility of this department are very variable: in the case of platforms not playing the role of a trusted third party, the customer service department is mainly intended for hosts. The customer service department answers their questions and helps them write ads. For platforms acting as a trusted third party, the customer service department is the interlocutor par excellence for all questions related to monetary transactions, complaints about hosts, about housing, and so forth. Therefore, the ease of contacting and communicating with this department is essential. To do this, different types of channels were set up: two-thirds of the platforms provide a 41phone number (but 55 % do not specify their opening hours), 62 % of the platforms indicate an email address, 38 % provide an internal email and only 10 % provide a postal address. On average, platforms provide 1 or 2 (1.7) channels to contact their customer department, but some have developed multi-channel access, including Onefinestay, which has 4 channels or EchangeImmo, Intervac, Le Collectionist, Troctachambre, Warmshower and Wimdu, which have 3.

In addition, it is important that the customer service department has the language skills to communicate with an international clientele: the language of the country of origin and one or two international languages seem to be the minimum. However, 47 % of the platforms offer only one language, including 14 of the 23 French respondents.

Several attempts have been made to obtain typical profiles of platforms based on their service offer. However, none has resulted in a typology likely to improve our understanding of a logic at work. Essentially, two categories are recurrent. The first category includes a very small number of platforms (3 to 6) that tick the maximum number of boxes and therefore offer a wide range of services. There we find the leader Airbnb and the two platforms managing luxury residences, Le Collectionist and Onefinestay, which claim to be sharing platforms despite their similarity to commercial agencies. Apparently, all have adopted an extensive innovation strategy (Djellal and Gallouj, 2006) to remain well differentiated from the numerous emerging competitors. The second category includes a dozen platforms that are the opposite: they offer the bare minimum in terms of services. These platforms seem to be following a refining offer strategy (Djellal and Gallouj, 2006), limiting their offers as much as possible to a few core competencies. Between these two groups, no clear structure emerges that would show the logics of particular services. Each platform opts for its own combination of services among all the areas mentioned above. Clearly, it is mainly a matter of differentiating one from the other and a matter of retaining customers interested in a particular combination of the elements of the service offering.

423. Characteristics of customer

relationship management

Several lessons can be drawn from the analysis we made of comments posted on the Internet by the users of hosting platforms: the platforms base all of their communication on the Internet, and they display a dual and fragmented offer, a very varied offer backed up by few services, outsourced quality management (the consequences of which can be problematic), and random customer management.

3.1 Communication based solely on the Internet

For the sharing platforms, the access routes to the service and the creation of the demand are only possible via a website. This is completely different from traditional hosting services, which use several means to communicate with their customers: advertising, front-line contact staff, physical media, billboards, supply consistency and the service manufacturing process. All of these significant elements refer to more abstract elements, such as ambiance and quality of service. Platforms do not have such elements at their disposal. Therefore, their communication is mainly based on promises: the promise of meetings, the promise of adventure, the promise of a wide and innovative offer, the promise of savings. Prices are often presented in terms of savings compared to traditional services and they sometimes omit certain fees that will have to be paid by customers. The abstract nature of offers is ameliorated by using multiple photos, location maps and direct language.

Therefore, the website is the only showcase of the proposed service, but it is also a key point for the judgement of the platform users: the quality of the service obtained is assessed according to its compliance with the promise posted on the site. Non-compliance triggers the most negative and often the most virulent opinions. While most clients have a favourable opinion of platform websites, they also highlight the vagueness of the financial aspects of platforms’ services and often the nonconformity of those services with the promises posted online.

433.2 A fragmented service offer

In traditional services, the service provider takes charge of all customer service from the information request to the delivery of the service and the final payment. Platforms offer the consumer a fragmented service between the services they provide (management of the website, financial aspects and customer service) and those provided by the hosts (reservations, customer contacts, accommodation, reception of customers…). Each transaction therefore involves two very different actors to provide the service to the consumer, who will then evaluate them.

The customer experience is based on smooth, easy and fast service processes. Most platforms have set up such processes for their services (mainly related to the Internet), but the final completion of the service remains in the hands of non-professional actors. Some comments left on the Internet extensively describe services that become a nightmare. Fragmentation of the service thus creates a potential risk for the customer that does not exist in traditional accommodation services and that can deteriorate the image of the platform.

The service relationship is usually defined as the set of connecting exchanges between providers and customers about the problem for which the customer is addressing the service provider (the purpose of the service). It is based on the exchange of information: a mixture of data related to the production and the realization of the service with informal data created during social exchanges between the service provider and the customer. This exchange of information involves well-defined roles assigned to all participants in the service relationship. It is an essential vector of customer loyalty: it seems that by nature, platforms can play only a small role on this vector because they do not control the verbal exchanges between consumers and accommodation owners. Fragmentation of a service in peer-to-peer hosting doubtless has a significant effect on the creation of this service relationship.

3.3 An extremely diverse offer with limited support services

Due to the possibilities of their computer tool, hosting platforms offer a very wide choice of housing. The offer is geographically very extensive, either in France, where the offer of accommodation covers the entire territory (including non-urban territory), or abroad, since some platforms 44publish housing in 161 countries (with an average of 81 countries). It is also extremely diverse because platforms offer a wide choice of housing (houses, apartments, boats, trailers, cabins). They even seek to expand their network spatially and by integrating other types of services, such as hotels, restaurants, business trips, and tourist services.

The scope of the offer is combined with a limited choice of additional services, which is much lower than the choice offered by traditional accommodation services. Certain support services reinforce the basic service (i.e., guarantee of services, payment facilities) but rarely result in the constitution of a true ecosystem favourable to the platform. These two elements tell us that platform services are intended to be relatively uniform mass services, seeking differentiation in some “plus” services.

3.4 Erratic quality management

Unlike professional services that implement quality management systems (such as SERVQUAL) and analyse the gaps between an ideal service and its effective delivery, platforms do not offer a service guarantee. In the case of an owner’s failure, the obvious concern expressed by customer service involves systematically releasing the platform from responsibility. Internet users who complain about a lack of reimbursement or compensation regularly emphasize this attitude.

For both services and goods, post-experience evaluation has been identified as the main determinant of future purchases. Indeed, the quality management system of Internet platforms is based on the evaluation of the customers and the ratings they attribute to the service providers: good evaluations should generate new business; bad evaluations should rapidly discourage potential users. To agree to stay in the house of a stranger, a customer needs some information to help him trust, as does the owner who entrusts his home to strangers. This information can be based on reliable customer evaluations and supplemented by the creation of customer profiles and the labelling of guests. However, platforms have weakened this system by highlighting positive opinions, while negative and very negative opinions are “moderated” if not simply erased. This “oriented” management of evaluations entails a direct loss of credibility and decreases the confidence that the rating system is supposed to build.

453.5 Random customer management

Many comments left on the Internet by customers relate to the contact staff. Customers expect hosts to behave professionally, that is, to be punctual, available, responsive and kind during both the booking process and the rental period. If the expected qualities are not present, customers’ reactions can be very negative, even hostile. The smooth operation of the platform service requires active customers who like to be autonomous and who accept reduced service because it results in lower prices.

Nevertheless, certain conditions must be respected by the service process: giving good information and limiting the uncertainty of the service are essential conditions. The most virulent criticisms expressed by customers are non-compliance with the information provided or the cancellation of a reservation at the initiative of the owner (sometimes just a few hours before arriving at the accommodation). These cancellations, which can be justified for technical reasons, are amplified by the competition between platforms: some owners deposit offers on several platforms with different prices and only accept the best proposal received.

Services delivered through sharing platforms are not formatted similar to those of an integrated firm or those of franchisees applying a network policy. Platforms do not manage the behaviour of owners or customers. They do not all have a customer service department that is truly dedicated to resolving service issues. Many critics attest to this, citing difficulty in accessing customer service, waiting times that are too long, communication that is only in English, no follow-up from one person to another, inappropriate automated answers, and a lack of assistance in the event of a serious problem. However, the progressive set-up of effective customer service departments that truly seek to help customers in difficulty appears as a differentiating strategy for advanced platforms, similar to increasingly rigorous verification of ads, both of which are signs that the sector is entering a mature stage.

46Conclusion

This research enables a better understanding of the new phenomenon of collaborative consumption.

Customers generally expect a perfect, fluid and seamless service, while the service offered by the peer-to-peer hosting platforms is by nature fragmented between two players who have little control over each other. In the sharing economy, the “heart of service” is indeed carried out by a non-professional individual, with all the hazards that this can cause. The performance of this individual-provider, who is ultimately the only one who is in contact with the consumer, is essential to the success of the interaction. Unfortunately, in the studied sharing platforms, the individual-provider is put in contact with a customer without any precaution other than general instructions published on the platform’s website, potentially resulting in very inappropriate behaviour.

The netnographic analysis reveals that the main strength of sharing platforms is the quality of their digital communication and the quality of their websites: both are perceived by customers as much better than those of traditional hosting businesses. Sharing platforms have created a communication style and an ergonomic quality, both of which have become an Internet communication standard that all service activities must satisfy.

However, the strength of the professional hosting offer concerns the core business of the hotel industry. The know-how and competence of the hotel industry are extremely powerful assets with respect to both accommodation and consumer relations. This know-how is often cited by consumers of traditional hosting services and concerns both the staff in contact at the hotel and the customer service staff. The netnographic analysis has revealed deep dissatisfaction when consumers do not receive help from somebody who considers their claims, an issue that is rather frequently reported by the users of peer-to-peer platforms. It is one of the flaws of the sharing model that platforms may take a long time to correct because they are not part of the economic model, which is to limit their involvement with the individuals they connect. In addition to this deliberate weakness of customer relations, 47some platforms systematically moderate negative evaluations, with the result of protecting dishonest suppliers and frustrating the consumers who are their victims.

More unexpectedly, many recriminations also concern the prices associated with sharing platforms: lower prices are one of the most powerful drivers of platform dynamics and are strongly emphasized on their websites. However, this argument may also produce some disappointment since additional costs, including the platform remuneration (which is often poorly accepted), are added to the announced price. Furthermore, some private individuals take unfair advantage of the dominant position they gain once the reservation has been made and the payment has been sent to the platform by asking an effective overall price that is higher than the agreed one. The “community” model at the heart of the platform system is supposed to automatically eliminate these “bad” experiences, but this model seems insufficient to prevent such issues from occurring.

The conclusion that emerges from these analyses is that the competition between companies in the traditional hosting sector and sharing platforms differs from that between companies in the same sector: players do not apply the same rules and do not obey the same logic. Sharing platforms operate in sectors without having truly developed a particular competence other than that of putting individuals in contact with each other. The classic analysis highlights the weaknesses of these models but does not explain the enthusiasm they arouse among consumers. Consumers seem to accept, at least to a certain extent, conditions from other individuals that they would not tolerate from professionals: the combination of lower cost, more direct exchanges and a sense of well-being leads customers to agree to take certain risks. These risks concern both the effectiveness of the service and the commercial relation or quality standards that will be observed. Two drivers can explain this new consumer behaviour. On the one hand, the peer-to-peer offer partly creates its own market: many collaborative consumers have been attracted by low prices that suddenly make holidays affordable that were previously too costly. On the other hand, a much broader and deeper movement of societies is probably at work: what is valued by consumers, what they accept and what they refuse is probably changing. This has to be taken into account in the future.

48Appendix

Characteristics of the 47 surveyed peer-to-peer

hospitality platforms (in alphabetical order)

|

Platforms |

Country of origin |

Ads |

Web traffic in France |

Type of transaction |

Financing mode |

|

9flats |

Germany |

108 179 |

175 010 |

Renting |

Commission |

|

Abritel |

UK |

1 520 499 |

4 360 000 |

Renting |

Subscription or commission |

|

Airbnb |

USA |

4 500 000 |

145 450 000 |

Renting |

Commission |

|

Amivac |

France |

27 939 |

622 720 |

Renting |

Sales |

|

Bedycasa |

France |

17 330 |

196 200 |

Renting |

Commission |

|

BeWelcome |

France |

28 682 |

64 870 |

Lending |

Free |

|

Cohébergement |

France |

3 010 |

153 010 |

Renting |

Commission |

|

Coinprivé |

France |

216 |

Unknown |

Renting |

Subscription + Advertisement |

|

CouchSurfing |

USA |

400 000 |

11 386 720 |

Lending |

Advertising |

|

Dormir pas cher |

France |

701 |

Unknown |

Renting |

Free |

|

Échange de maison |

Canada |

5 855 |

Unknown |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

EchangeImmo |

France |

1 955 |

Unknown |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

Échanger sa maison |

USA |

9 538 |

Unknown |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

Geenee |

UK |

15 863 |

Unknown |

Swapping |

Free |

|

Global Freeloaders |

Australia |

121 074 |

Unknown |

Lending |

Advertisement |

|

Guesttoguest |

France |

388 717 |

296 120 |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

Home for Exchange |

The Netherlands |

7 645 |

115 230 |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

Homelidays |

UK |

1 563 640 |

2 326 110 |

Renting |

Subscription or commission |

|

Homelink |

France |

7 992 |

194 630 |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

Hospitality |

Germany |

791 601 |

118 620 |

Lending or Swapping |

Free |

|

Housetrip |

UK |

711 987 |

559 240 |

Renting |

Commission |

|

Iha Holiday Ads |

Switzerland |

46 879 |

360 910 |

Renting |

Subscription |

|

Intervac |

Switzerland |

5 205 |

88 050 |

Swapping or Renting |

Subscription |

| 49

Knok |

Spain |

9 209 |

Unknown |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

Le Collectionist |

France |

1 465 |

Unknown |

Renting |

Commission |

|

Love Home Swap |

UK |

9 813 |

184 200 |

Swapping or Renting |

Subscription |

|

Maravista |

France |

1 043 |

Unknown |

Renting |

Subscription |

|

MediaVacances |

France |

13 781 |

779 055 |

Renting |

Subscription |

|

Misterb&b |

USA |

53 342 |

474 920 |

Renting |

Commission |

|

Morning Croissant |

France |

4 039 |

129 300 |

Renting |

Commission |

|

My Nomad Family |

France |

846 |

Unknown |

Renting |

Commission |

|

NightSwapping |

France |

4 000 |

Unknown |

Renting |

Commission |

|

Onefinestay |

UK |

7 598 |

127 630 |

Renting |

Commission |

|

Only Apartments |

Spain |

159 206 |

446 060 |

Renting |

Commission |

|

Ouloger |

France |

3 111 |

Unknown |

Renting |

Subscription |

|

PAP Vacances |

France |

22 359 |

850 030 |

Renting |

Subscription |

|

Pour les Vacances.com |

France |

7 150 |

Unknown |

Renting |

Subscription |

|

Profvac |

France |

475 |

Unknown |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

Room4exchange |

Spain |

154 |

Unknown |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

Roomlala |

France |

35 262 |

1 110 000 |

Renting |

Subscription |

|

Se loger vacances |

France |

154 799 |

Unknown |

Renting |

Subscription |

|

Servas |

Switzerland |

12 341 |

71 130 |

Lending |

Subscription |

|

Switchome |

France |

1 752 |

Unknown |

Swapping |

Sales |

|

Trocmaison |

UK |

54 699 |

126 050 |

Swapping |

Subscription |

|

Troctachambre |

France |

90 |

Unknown |

Swapping |

Commission |

|

WarmShower |

USA |

89 664 |

526 070 |

Lending |

Free |

|

Wimdu |

Germany |

166 769 |

2 145 860 |

Renting |

Commission |

References

Albarède M. (2015), Cartographie des acteurs de la consommation collaborative. ShaREvolution, available at: https://www.entreprises.gouv.fr/files/files/directions_services/cns/ressources/9_38_cartographie_des_modeles_et_des_offres_de_consommation_collaborative.pdf (accessed 13 december 2018).

Alcantara Guimaraes J. G., Franco V. R. and Castro Lucas de Souza C. (2018), “Sharing economy: a review of the recent literature”, European Review of Service Economics and Management, vol. 2, no 6, p. 75-95.

Baranger P., Dang Nguyen G., Leray Y. and Mével O. (2016), Le management opérationnel des services (2d edition), Paris, Economica.

Bardhi F. and Eckhardt G. (2012), “Access based consumption: The case of car sharing”, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 4, no 39, p. 881-898.

Belk R. (2014a), “You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption on line”, Journal of Business Research, vol. 8, no 67, p. 1595-1600.