Economie du partage : un bilan de la littérature récente

- Type de publication : Article de revue

- Revue : European Review of Service Economics and Management Revue européenne d’économie et management des services

2018 – 2, n° 6. varia - Auteurs : Alcantara Guimarães (João Gustavo), Rosa Franco (Víthor), Castro-Lucas de Souza (Cristina)

- Résumé : Cette étude a réalisé un bilan des publications sur cette nouvelle tendance économique qu’est l’économie du partage, en s’appuyant sur Google Scholar pour la période 2006-2016. Elle a sélectionné les 649 articles les plus pertinents et a testé les éventuelles corrélations thématiques. Elle discute les thèmes relatifs aux défis juridiques et aux nouveaux modes de consommation permis par l’économie du partage, ainsi que les relations entre la thématique du covoiturage et celle de la durabilité.

- Pages : 77 à 96

- Revue : Revue Européenne d’Économie et Management des Services

- Thème CLIL : 3306 -- SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES -- Économie de la mondialisation et du développement

- EAN : 9782406086338

- ISBN : 978-2-406-08633-8

- ISSN : 2555-0284

- DOI : 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-08633-8.p.0077

- Éditeur : Classiques Garnier

- Mise en ligne : 15/10/2018

- Périodicité : Semestrielle

- Langue : Anglais

- Mots-clés : Économie du partage, séries temporelles, classification hiérarchique, catégorisation thématique

Sharing economy: A review

of the recent literature

João Gustavo Alcantara Guimarães1

University of Lille (France)

Víthor Rosa Franco,

Cristina Castro-Lucas de Souza

University of Brasília (Brazil)

Introduction

The so-called sharing economy is a subject of growing worldwide interest insofar as this economic phenomenon has attracted the attention of entrepreneurs, investors, governments and third sector entities. The scope of the sharing economy’s uses and practices reaches important topics such as sustainability, solidarity, connectivity, reputation, as well as new forms of exchange across digital communities. The term “sharing economy” was first used by those who studied innovation mediated by the Internet to describe the growing phenomenon of citizens who freely shared skills and knowledge in collaborative online efforts like Wikipedia and open source software development (Puschmann and Alt, 2016). Over time, the term came to define economic activities that were born from pure innovation or from reinterpretations of traditional business models, but built massively on top of information and communication technologies, whether or not involving the use of money as a means of exchange (Matzler et al., 2015).

78In fact, the activities and ideas that make up the sharing economy are not new. Throughout history, many successful companies have been built around exchange and rental of goods and services. Both informal and personal collaboration activities have had a long thrive in communities and niches (Schor, 2014). In this context, the sharing economy seems to suggest new definitions – or at least question the real relevance – of the need of property regarding the enjoyment of goods, thereby featuring as a service economy. Thus, the sharing economy is essentially a service economy bringing innovation on the execution processes of services, as well as on the proposal of new services.

According to the World Bank (2016), services account for about 68.07 % of GDP of the global economy, which represent an increase of 13.8 % over the last twenty years. However, measuring the process of value generation in the service sector is not obvious. The constant comparison with industry, which has clear and measurable results, diverges from the service sector. The service value is related to what it will give to those who consume it, something unknown and immeasurable until it occurs.

Besides that, according to many literature reviews (Bardhi and Eckhardt, 2012; Cheng, 2016; Maselli et al., 2016), studies on the sharing economy domain have faced some additional hurdles from the semantic point of view. There is a plethora of expressions aiming to grasp the same idea: sharing economy, collaborative consumption, collaborative economy, shared economy, peer economy, gig economy, access economy, on-demand economy and others. These terms need to be investigated more carefully before they can be treated as equals. For instance, most of the literature on the theme considers “sharing economy” as a broader socio-economic phenomenon, while “collaborative consumption” is more focused on the analysis of changes related to consumer behavior. For Martin (2015), the use of both denominations as synonymous and the close relationship between the terms occurred probably after the publication of the book “What’s mine is yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption” (Botsman and Rogers, 2011), which became a reference book on the theme. Therefore, the unclear use of potentially different concepts brought by this book turned a starting point to identify which of those terms became dominant to summarize the phenomenon in question.

During the decade from 2006 to 2016, the exploration of the sharing economy construct through articles and papers, enlisted some topics 79related to mobility technologies and permanent connectivity as well as the disintermediation on many different types of businesses and raised impact on different subjects like sustainability, working rights, regulation, monetization and others.

The aim of this paper is to analyze the publication trend about sharing economy in terms of the number of papers and the nature of topics addressed over that decade. To achieve this goal, we applied methodological tools that can be fitted well enough to support an evolutionary mapping. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) makes it possible for the researchers to identify the correlations established among some variables at a given time and, therefore, to map the evolution of the research themes over a period. Also, time series analysis (Hamilton, 1994) can be used to predict and evaluate quantitative differences over time.

The details of the methodology will be explained in section 2, but one can say briefly that the MCA performs a content analysis over selected papers to constitute derived research categories, therefore treated as variables. The results are maps with the trajectory of the main categories of a thematic area studied along a given period. Frequencies for each category are presented in temporal perspective, allowing one to identify emerging or declining issues. The analyses presented in this research are carried out on a database constructed by the authors by collecting bibliometric data from selected papers published from January 2006 to December 2016.

This paper is structured as follows. First, we present a conceptual review including the most common aspects studied and some theoretical developments for the sharing economy theme. In the methodology section, we provide a detailed description of the procedures used: a) to establish the expression “sharing economy” as the prominent one used to address the social and economic phenomenon in question and b) to present how we established the categories that describe the most frequent subjects addressed by the sharing economy research. The third section is devoted to the results and the discussion. It shows the distribution of articles according to the established categories and provides a mapping of the trajectories of these categories over the last decade. It also discusses the thematic proximity between themes and identifies which topics are declining and which are rising within the general field of sharing economy. The conclusion sketches a short research agenda to better explore the thematic gaps.

801. Conceptual Review

For several decades, numerous studies have been conducted on the “sharing” topic, from the simplest associations of barter and items exchange to the latest interest on consumer behavior. Mainly after the advent of Web 2.0, different sharing practices have gained strong dissemination. According to Belk (2013), in a broad sense, the Internet itself became a giant pool of shared content that can be accessed by anyone. Furthermore, the permanent connectivity promoted the meeting of people with converging interests, facilitating the emergence of virtual communities, while allowing the contact and exchange among individuals directly (peer-to-peer). Botsman and Rogers (2010, p. 30) emphasized this fact as a socio-economic change, attesting that “in an era of individualism, the peer-to-peer sharing involves the re-emergence of community”.

Therefore, many studies (Bardhi and Eckhardt, 2012; Matofska, 2014; Ranchordas (2015) have attempted to define the sharing economy. Some of them consider the sharing economy as a major trend that emerged with the global economic recession allied to social concerns about sustainable consumption to drive individuals and society to explore more efficiently the use of resources and products (Jiang and Tian, 2016). The term is also intended to capture new, more collaborative forms of creation, production, distribution, trade and consumption of goods and services that are being enabled by new technological platforms (Pick and Dreher, 2015). According to Matofska (2014, p. 1), the sharing economy is “a socio-economic ecosystem built around the sharing of human and physical resources. It includes the shared creation, production, distribution, trade and consumption of goods and services by different people and organizations”.

In fact, there are some combinations of motivations that steer people onto the sharing economy domain, which in many ways represent a new attitude towards some economic principles. According to Denning (2014), instead of planning the lives on the premise of acquiring and owning more private property, a new generation is finding meaning and satisfaction in having shared access to things and interacting with other 81people in the process. Bardhi and Eckhardt (2012, p. 881) summarized this phenomenon in their concept of “access-based consumption,” saying that: “Instead of buying and owning things, consumers want access to goods and prefer to pay for the experience of temporarily accessing them”.

Besides the access-based consumption, the sharing economy also gave a big room to the contemporary sustainability concerns. The main argument about the potential positive effect that the sharing economy brings to the sustainability concerns is the reduction of the produced goods (Daunoriene et al., 2015, p. 839). Once the basilar motto is “pay to use, not to buy”, some sharing economy business models became paramount to disseminate and drive sustainable consumption modes.

As expected in such a fast-moving domain, the progress led to some regulation issues that have continued to evolve. Some of the main subjects on which regulation is being challenged are technology, workers’ rights, tax confusion and liability. From the technology perspective, the phenomenon is usual: “the technology is developing faster than the regulation” (Maselli et al., 2016, p. 8). Yet there is a broader view of this gap that Ranchordas (2015, p. 2) summarized saying that “regulation is traditionally characterized by the stability and continuity of rules. Therefore, regulators often delay innovation by fitting innovative services in existing legal categories and failing to update the extant legal framework to the current state of technology”.

From the workers’ rights perspective, several studies came to approach class-action suits against Uber, Lyft and other ride-sharing providers. For instance, Uber provides the crucial and expensive online system that supports and drives ride-sharing, but the drivers provide and maintain their own cars, as well as the smartphones that connect them to the online system (Ritzer, 2014). In this case, almost all the risks are on the side of the workers. According to Cherry (2016, p. 26), “the crowdwork model may be more of a throwback to the (Taylorist) industrial model, incorporating the efficiency and control of automatic management, without the industrial model’s job security or stability.” Yet, on the other side, according to Sundararajan (2015, p. 1), “start-ups that rely on a large pool of smartphone-toting casuals working irregular hours may find that their business models are no longer viable”.

The discussions on the multiple themes continued to evolve. In terms of liability, the case study with the highest number of harm or adverse 82occurrences is Airbnb. Besides the usual lawsuits about damages on guests’ houses, Airbnb is being treated as a vector of racism. On a recent study, Todisco (2014) criticized the lack of control and regulations over the Airbnb proceedings about acceptance of guests. In a way around and opposite to the regular process of guest acceptance by the hotel, Airbnb provides the host with information about the prospective guest that “serves as a heuristic for race” before the host accepts or declines a guest’s request, said Todisco (2014, p. 2). Armed with a guest’s racial information, hosts have “a nearly unfettered ability to decline potential guests”.

Yet, another surprising aspect Airbnb brought up about the housing challenges was the analysis over low-cost accommodations offerings in some cities. According to Ellen (2015), there is excess capacity within the existing housing stock. As long as people are compensated, they share their homes and this could impact housing public policies in the future.

As in many knowledge domains, some contradictions arose with the increase of studies on sharing economy as well. The most positive perceptions assure that the online platforms empower individuals, reduce transaction costs and create a more inclusive economy (Khanna and Khanna, 2014). Some concerns started with the fact that the “added-value” of the sharing economy relies on access, which is a technology dependent aspect. But, sometimes technology acts as a barrier to participation for a general population and increases existing obstacles for disadvantaged populations. These populations may not have the resources to take advantage of the sharing economy (Cheng, 2014). According to Richardson (2015, p. 123), “the sharing economy simultaneously masks new forms of inequality and polarizations of ownership”, emphasizing the replications of “old patterns of privileged access for some and denial for others” (Robinson, 2014, p. 1).

To handle the wide range of subjects related to the general theme of sharing economy, this research performed a state of the art of the literature. It started looking for the main terms that involve a sharing dimension within the context set up in the previous section. Then it carried out a deep analysis of the works published over the decade from 2006 to 2016 in order to establish the main topics addressed in these works and how they have evolved.

832. Method

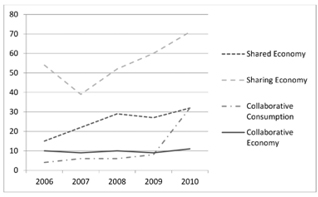

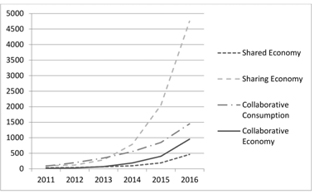

For the selection of the papers used in this work, we used the Google Scholar database, given that it is one of the largest free search engines of scientific articles. Following Botsman and Rogers (2011), four of the most frequent terms used to talk about the sharing activities in question guided our selection for papers, namely: “sharing economy”, “shared economy”, “collaborative economy” and “collaborative consumption”. Table 1 shows the quantity of papers for each year, between 2006 and 2016, according to the different terms used.

|

Year |

Shared Economy |

Sharing Economy |

Collaborative Consumption |

Collaborative Economy |

Total |

|

2006 |

15 |

54 |

4 |

10 |

83 |

|

2007 |

22 |

39 |

6 |

9 |

76 |

|

2008 |

29 |

52 |

6 |

10 |

97 |

|

2009 |

27 |

60 |

8 |

9 |

104 |

|

2010 |

32 |

71 |

32 |

11 |

146 |

|

2011 |

33 |

102 |

86 |

18 |

239 |

|

2012 |

41 |

120 |

197 |

28 |

386 |

|

2013 |

67 |

288 |

349 |

70 |

774 |

|

2014 |

98 |

785 |

553 |

188 |

1,624 |

|

2015 |

190 |

2,050 |

848 |

405 |

3,493 |

|

2016 |

464 |

4,750 |

1,450 |

956 |

7,620 |

|

Total |

1,018 |

8,371 |

3,539 |

1,714 |

14,642 |

Tab. 1 – Frequency of papers per term, per year and total for each.

Graphically, it is easy to identify what expression was dominant in the timeframe. Figures 1 and 2 show those data in a temporal trend graphic, where it can be seen that “sharing economy” is the most used term of all four. The Figures are separated given that after 2010 the number of publications has grown in an expressive faster rate. Therefore, 84variations between 2006 and 2010 would not be possible to compare if the graphic was in a single scale.

Fig. 1 – Temporal trend for all four terms between 2006 and 2010.

Fig. 2 – Temporal trend for all four terms between 2011 and 2016.

85Given that “sharing economy” showed the highest frequency of published papers, and the other terms probably are correlated with it, the following analyses contemplate only the papers with those terms. We used the software Publish or Perish (Harzing, 2010) to gather more specific information about the papers we found previously. The criteria used to refine the set of papers were: a) it uses the term “sharing economy”; b) it was published between 2006 and 2016; and c) it had at least one citation, as criteria for relevance of the selected papers. With those criteria, from 8,371 papers we stood with distinct 1,312 and we used their abstracts as the text base to determine whether the paper is about sharing economy. From those, 649 were studies about sharing economy specifically. Among the excluded papers, 34 were books with no abstracts, 87 were papers whose abstracts couldn’t be accessed (not free articles), 18 were articles with no abstract, 13 were impossible to access (deactivated links or error web pages), 492 were off topic, just slightly mentioning sharing economy, and 19 were repeated versions of an already selected paper.

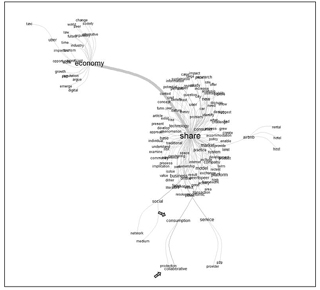

We started the analysis with a link map. The algorithm to build link maps uses metrics of frequency and distance between words to identify the central concepts and to suggest what are the main relationships (links) between these concepts and the others. In general, it is assumed that when there are small distances and high frequency of occurrences amongst certain words, there is a greater proximity in the concepts that these words represent. It is based on this assumption that link maps between words are built, having sets of texts as the input.

Graphically, a larger or smaller distance between words represents a stronger or weaker relationship between these words and, consequently, between the concepts they represent, based on the total set of texts. In this analysis, we selected all the remaining 649 abstracts as the input for the construction of the link map, as shown in figure 3.

86

Fig. 3 – Link map based on the words from the 649 selected papers.

Since all the abstracts were extracted from papers about sharing economy, it was expected that the concepts of “share” and “economy” formed the attraction poles of the other concepts. It is possible to verify in Figure 3 that, in fact, this happened. The point that draws attention is that among several concepts continuously associated with the phenomenon of sharing economy, the expression formed by the words “collaborative” and “consumption” – highlighted by the two grey arrows in the figure – appears far from the words poles.

As exposed in the introduction of this paper and according to the conceptual review, the terms “sharing economy” and “collaborative consumption” were usually treated as synonyms. However, what the map suggests is that this relationship is not so direct. More than that, 87the word “collaborative” lies at one end of the links between words, suggesting a weak relationship with “share”.

To identify thematic clusters within the sample of abstracts we applied Reinert’s method (Reinert, 1987) onto the abstracts of the selected 649 papers. Basically, the Reinert method proposes a statistical approach divided into two steps: the first one is responsible for identifying the frequencies of words and the distances between them in order to find the semantic contexts, which would be the classes. Then the second step is to identify the most representative words of these classes based mostly on the frequency of them. We used the free software IRAMUTEQ (Camargo and Justo, 2013) to identify these clusters due to its implementations of Reinert’s algorithms.

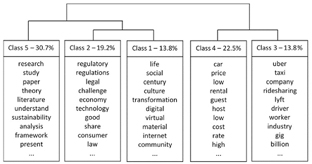

Five thematic domains were found, as shown in Figure 4.

Fig. 4 – Dendrogram of the 649 searched papers’ abstracts.

Those thematic domains are abstractly expressed, initially, by their class numeration. In Figure 4, the percentages represent the text segments each category comprises based on the full set of 649 papers’ abstracts (100 %). For instance, it is possible to identify that most of the terms (53.2 %) are grouped into classes 4 and 5. Below the class number and its percentage, we show the ten most common terms for each class, sorted from highest to lowest frequency. The distribution shown in the dendrogram presenting the thematic domains relates to 88each category we will use to classify the 649 specific papers. In other words, once we have the thematic domains already identified we can use them as categories and apply the Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) to analyze the proximity of the themes in the Sharing Economy literature. The descriptions of each category were defined according to the conceptual review, as shown in Table 2.

|

Category Name |

Correspondent Class |

Description |

|

New consumption |

Class 1 |

It discusses changes in the consumer behavior, highlighting the social and economic aspects of the sharing economy (usufruct vs. property, hyper-sociability, new communities), which is based on new digital platforms. It gives emphasis on collaborative approaches enacted by the Web 2.0 and the permanent connectivity. |

|

Legal challenge |

Class 2 |

It addresses the legal challenges that have arisen with the sharing economy, including studies about the regulation of new economic activities, tax collection, labor impacts (from the legal perspectives), business governance, and also uncertainties about the accountability of individuals in informal exchanges. |

|

Ride industry |

Class 3 |

It discusses various aspects of the car rental and ride market (ride-sharing, car-sharing, bike-sharing) and short-term accommodation (Couchsurfing, Airbnb), using mainly Uber and Airbnb businesses models as the benchmark, as well as their impacts on the labor market, profit margins and new forms of competition in these industries. |

|

Low-cost |

Class 4 |

It addresses cost reduction in several ways, bringing together the researches that highlighted the relevance of the price over other criteria and even not monetized exchanges. It also points to the informal market and transactions among individuals, having the Internet as the platform. |

| 89

Sustainability |

Class 5 |

This category hosts the productions that analyze the sharing economy looking to some potential future scenarios and socio-economic impacts when linked to issues like sustainability and social responsibility, as well as the new concepts of community. |

Tab. 2 – Name and description of the categories used for the MCA, with correspondent class in which it appeared in the dendrogram.

3. Results and Discussion

The initial outcomes brought suggestive relations among the categories we found and other results presented on previous studies. For instance, the five categories this study has found relate in some way with Martin (2015) content analyses. Martin (2015) identified that the Sharing Economy is framed within six relevant characteristics: (1) an economic opportunity, (2) a more sustainable form of consumption, (3) a pathway to a decentralized, equitable and sustainable economy, (4) creating unregulated marketplaces, (5) reinforcing the neoliberal paradigm, and, (6) an incoherent field of innovation.

Based on our findings, we can link Martin’s economic opportunity (1) to the ride industry, the sustainable consumption (2) to the new consumption, the pathway to an equitable and sustainable economy (3) to sustainability and the unregulated marketplaces (4) to the legal challenge.

Cheng (2016) also found five categories when tracked articles specifically focused on the impact of Airbnb on the hospitality industry in Asia. The categories were: a) lifestyle and social movement; b) consumption practice; c) sharing paradigm; d) trust; and e) innovation. The links between Cheng’s categories and ours are not so direct. There is also a contextual difference that is critical: our study filtered articles on Sharing Economy in all scopes. Cheng’s work focused only on the hospitality industry in Asia.

90In order to build the analysis using the MCA framework, we applied the five categories presented on Table 2 to classify all the 649 papers. In other words, we analyzed all the 649 papers to identify which categories each paper could fit in, considering that one single paper can match more than one category.

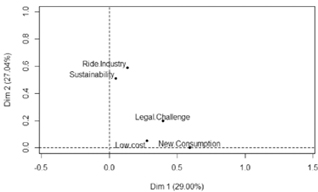

Again, the distance between the thematic categories suggests the proximity of the subjects they are related. According to the thematic categories found, Figure 5 shows distances amongst them, considering the 649 papers from 2006 to 2016, using MCA. It is possible to identify that, in general, papers about ride industry also address Sustainability. Papers devoted to Legal Challenge usually also address Low Cost and New Consumption topics.

Fig. 5 – Distances between the thematic categories of the publications

on “sharing economy” (649 papers from 2006 to 2016, using MCA).

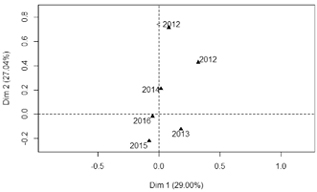

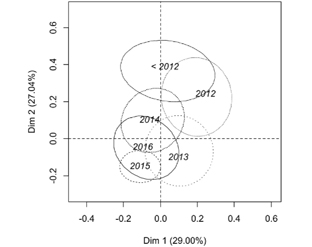

The MCA is also used to compare the distance between thematic developments over the time. For a better understanding of the evolution of themes over time, Figures 6 and 7 should be analyzed together. For graphic representation purposes, the years prior to 2012 were gathered together (<2012), given the small number of publications in that period. Figure 6 shows that there are differences in thematic development for 91each year, represented by the different positions of each year in the graph. However, looking at the overlap of the confidence ellipses of all the studied years in Figure 7, it is possible to identify that these differences may not be as pronounced, specifically for the papers published from 2013 to 2016. In fact, for this period, there are large areas of intersection between the ellipses of each year.

In other words, from 2006 to 2016 all Sharing Economy articles addressed the five categories found, but papers from 2006 to 2012 focused on different themes of the papers that were published between 2013 and 2016. This perception is clearly shown when comparing, in Figure 7, the distance between papers published before 2012 (<2012) and papers published in 2016, where there is no overlap of confidence ellipses.

Fig. 6 – Distances between the years’ propensities for thematic categories,

given the group of sharing economy papers, using MCA.

Fig. 7 – Confidence ellipsis for thematic propensities for each year,

given the group of sharing economy papers, using MCA.

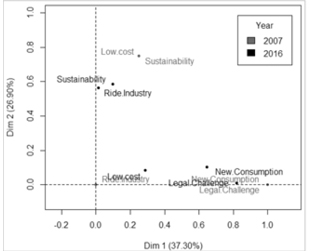

Finally, Figure 8 shows a 10-year gap comparison, given that the low number of publications in 2006 made it not possible to compare it with 2016. This is a first step to discuss the evolution of the categories along that decade and, consequently, the dispersion and the concentration of the studies about Sharing Economy. According to the graph, in 2007 Sustainability ran together with Low Cost matters. In the same year, New Consumption was mostly related with Legal Challenge discussions, while Ride Industry ran alone. In 2016, it is possible to see a different trend that brings together Ride Industry and Sustainability, while Low Cost started to run alone, probably because of the proliferation of companies trying to clone Uber and Airbnb successes.

93

Fig. 8 – Distances between the thematic categories of sharing economy papers, using MCA, for the years 2007 and 2016.

Conclusion

The objective of this article was twofold: to analyze the time trend of the number of publications related to the sharing economy phenomenon and identify the most relevant thematic categories addressed in this subject. The results showed that from 2006 to 2016 the term “sharing economy” was the most used to summarize the new dynamics of “sharing”, including new consumption patterns, sustainability concerns, sharing of idle assets, legal responsibilities in unregulated markets and a new sense of community, all brought together by technological advances and the spread of Internet capabilities.

94The number of articles related to the sharing economy published each year has been growing significantly, having doubled the amount of publications each year, starting in 2013. On the one hand, this finding demonstrates the recent relevance of the subject for scientific research, on the other, the content analysis of the abstracts showed the themes that permeate the researches still largely overlap. Perhaps this continuous blend of issues may be one of the factors that hinder a precise definition of the Sharing Economy phenomenon. As a suggestion for a future research agenda, it would be relevant to deepen the stratification of the categories identified in this study in search of a systematization of the phenomenon. For instance, according to the results obtained, the expression “collaborative consumption”, commonly used as a synonym for the sharing economy, does not appear to be so closely linked. Maybe this relationship could find more strength when understood as a category of the Sharing Economy, not as a synonym.

According to the main research paths identified by this study and defined in five thematic categories, researchers generally investigate the relationship between sustainability and the emergence of the ridesharing industry, as well as the legal challenges involved in the rise of new types of consumption and their relationships with service providers.

In short, the advent of the Internet and its means to transform everyday tasks has profound economic impacts. This is the substrate where practices related to the Sharing Economy are born, characterizing a field of innovation still in intense evolution, with many gaps to be filled. It is a comprehensive subject that brings together topics as distinct as sustainability, workers’ regulations in the digital age, significant changes in consumer lifestyles, new ways of monetizing idle assets and other recent transformations in society. However, the sharing economy can also be seen as just a new name given to reinterpretations of well-known business models, now leveraged and expanded by the permanent connectivity available in many societies. This inaccurate characterization may be a sign that there is much to be understood about Sharing Economy in all its extensions.

Future studies should use more elaborated algorithms to evaluate thematic content and dominance within papers, in such a way that trends and effectiveness in varied themes can be more precisely understood. The large amount of possible definitions and the flexibility of practices make sharing economy a new fruitful area of research.

95References

Bardhi F. & Eckhardt G. (2012), “Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing”, Journal of Consumer Research, 39 (4), p. 881-898.

Belk R. (2013), “You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online”, Journal of Business Research, 67 (8), p. 1595-1600.

Botsman R. & Rogers R. (2010), “Beyond Zipcar: Collaborative Consumption”, Harvard Business Review, 88 (10), p. 30.

Botsman R. & Rogers R. (2011), What’s mine is yours: how collaborative consumption is changing the way we live, London, Collins.

Camargo B. V. & Justo A. M. (2013), “IRAMUTEQ: Um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais”, Temas em Psicologia, 21 (2), p. 513-518.

Cheng D. (2014), Is sharing really caring? A nuanced introduction to the peer economy, Report of the Open Society Foundation – Future of Work Inquiry.

Cheng M. (2016), “Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57 (August), p. 60-70.

Cherry M. A. (2016), “Beyond Misclassification: The Digital Transformation of Work”, Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal, 37 (3), p. 577-604.

Daunorienė A., Drakšaitė A., Snieška V. & Valodkienė G. (2015), “Evaluating sustainability of sharing economy business models”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 213 (1), p. 836-841.

Denning S. (2014), “An economy of access is opening for business: five strategies for success”, Strategy & Leadership, 42 (4), p. 14-21.

Ellen I. G. (2015), “Housing Low-income Households: Lessons from the Sharing Economy?” Housing Policy Debate, 25 (4), p. 783-784.

Hamilton J. D. (1994), Time series analysis, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Harzing A. W. (2010), The publish or perish book, Melbourne: Tarma Software Research.

Jiang B. & Tian L. (2016), “Collaborative consumption: Strategic and economic implications of product sharing”, Management Science, 64 (3), 1171-1188.

Khanna A. & Khanna P. (2014), “Disciplining the Sharing Economy”, Project Syndicate Opinion Page, September 25.

Martin C. J. (2015), “The sharing economy: a pathway to sustainability or a new nightmarish form of neoliberalism?” Ecological Economics Journal, 121, p. 149-159.

Maselli I., Lenaerts K. & Beblavy M. (2016), Five things we need to know about the on-demand economy. Centre for European Policy Studies, Essay No. 21.

96Matofska B. (2014), What is the sharing economy. The People Who Share. Retrieved from: www.thepeoplewhoshare.com.

Matzler K., Veider V. & Kathan W. (2015), “Adapting to the sharing economy”, MIT Sloan Management Review, 56 (2), 71-77.

Pick F. & Dreher J. (2015), “Sustaining hierarchy–Uber isn’t sharing”, Kings Review-Magazine, 5th May, p. 1-8.

Puschmann T. & Alt R. (2016), “Sharing Economy”, Business & Information Systems Engineering, 58 (1), p. 93-99.

Ranchordas S. (2014), “Does Sharing Mean Caring? Regulating Innovation in the Sharing Economy”, Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology (Winter 2015).

Ranchordas S. (2015), “Innovation Experimentalism in the age of the sharing economy”, Lewis & Clark Law Review, 19 (4), p. 871-924.

Reinert P. M. (1987), “Classification Descendante Hiérarchique et Analvse Lexicale par Contexte-Application au Corpus des Poésies d’Arthur Rimbaud”, Bulletin of Sociological Methodology / Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, 13 (1), p. 53-90.

Richardson L. (2015), “Performing the sharing economy”, Geoforum, 67, p. 121-129.

Ritzer G. (2014), The “Sharing” Economy, Uber, and the Triumph of Neo-Liberalism. George Ritzer, available at: https://georgeritzer.wordpress.com/2014/11/05/the-sharingeconomy-uber-and-the-triumph-of-neo-liberalism.

Robinson R. (2014), “Virtual Redlining and the Myth of Opportunity in the Sharing Economy”, Position Paper, the Open Society Foundation.

Schor J. (2014), “Debating the sharing economy”, Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 4 (3), p. 7-22.

Sundararajan A. (2015), “A safety net fit for the sharing economy”, Financial Times, June 22.

Todisco M. (2014), “Share and Share Alike: Considering Racial Discrimination in the Nascent Room-Sharing Economy”, Stanford Law Review Online, 67, p. 121-129.

World Bank Open Data (2016), “Services, etc., value added (% of GDP)”, available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.SRV.TETC.ZS. (accessed May 5, 2018).

1 Corresponding author