Jeter un pont entre expériences de service et innovations de service Un nouveau modèle pour comprendre l'avenir des services

- Type de publication : Article de revue

- Revue : European Review of Service Economics and Management Revue européenne d’économie et management des services

2018 – 2, n° 6. varia - Auteur : Rubalcaba (Luis)

- Résumé : Cet article fournit un cadre théorique pour faire le lien entre les expériences de service et les innovations de service. Il analyse l'innovation de service à la lumière des expériences de service en termes de connexion et d'engagement des personnes. L'hypothèse est que le contexte social est un facteur de connexion majeur et que les rencontres humaines sont à la base du « pont » social. L'article propose également un modèle en dix dimensions pour comprendre les nouvelles tendances de l'innovation de service.

- Pages : 17 à 49

- Revue : Revue Européenne d’Économie et Management des Services

- Thème CLIL : 3306 -- SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES -- Économie de la mondialisation et du développement

- EAN : 9782406086338

- ISBN : 978-2-406-08633-8

- ISSN : 2555-0284

- DOI : 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-08633-8.p.0017

- Éditeur : Classiques Garnier

- Mise en ligne : 15/10/2018

- Périodicité : Semestrielle

- Langue : Anglais

- Mots-clés : Services, expérience, innovation, social, rencontre, éducation

Bridging service experiences

and service innovation

A new model for understanding

the future of services

Luis Rubalcaba1

University of Alcalá

Introduction

Services and service innovations are becoming more open and more social. This is because the linkages between companies and consumers and between organisations and users to co-produce services increasingly interact with a whole range of institutions and social actors. Service innovation can even become social innovation when multiagent frameworks apply and bilateral co-productions are transforming into multilateral ones. Economists (Djellal and Gallouj, 2012; Rubalcaba, 2016; Windrum et al., 2016) have explored the bridge between service innovation and social innovation from a systemic and multiagent perspective. However, this approach has not yet been integrated with the background coming from the service experience research (e.g., Sundbo, 2015c). The experience economy is a growing research area that has recently met the service literature because services are the protagonists of most of the outstanding experiences for citizens in fields such as creative industries, digital services, tourism, and cultural, community and personal services.

18Building on Sundbo’s (2015c) exploration of the relationships between services and experiences, this article illustrates the role of the social as a link between services and experiences and role of the experience in the move from service innovation to social innovation. Innovations in services increasingly link to the connection between individual experiences and social factors in the globalised world. For example, the collaborative economies for accommodation and transport illustrate how individuals look for new experiences in services, using new ways of co-producing and new services goals, for which social aspects (and social networks) are increasingly relevant.

This article articulates a theory about how to integrate service experiences with service innovation. Categories such as service encounter are at the heart of this integration. Also, the article illustrates the character of service innovation in the light of service experiences in terms of connecting people (connectivity to others and self-awareness) and engaging people (trust and freedom). Different service experiences occur depending on the social context. The hypothesis of this article is that the social is a factor, among others, useful to bridge service experiences and service innovation, and human encounters in services are the base to procure a social building (combination of growth and welfare) in services. This will also help to reinforce the bridge between service innovation and social innovation research (Windrum et al., 2016). In addition, this article proposes a new model for understanding trends in services innovation as shifting equilibria among tensions across paired dimensions spanning five facets of services innovations: their nature, goals, means, agents, and control. Different equilibria among the tensions across these ten dimensions produce different service solutions; some produce different experiences in users.

1. Service encounters and service

experiences from a social perspective

Economists understand service encounters as encounters between customers and employees in service deliveries (Sundbo et al., 2015). Conceptions of service encounters derive from very different service 19theories, such as Gronroos (1990), Gadrey and Gallouj (1998), and Vargo and Lusch (2008). An encounter is often defined as a trust-based meeting between producers and users leading to what the service marketing and management literature (e.g., Normann, 1991) calls the “moment of truth.” All services are social because all humans are social beings. However, not all human interactions are service-based or service-oriented. Not every meeting is a service encounter. Although all human activities may have a service element, a service encounter needs service intentionality, trust, impact, and interaction. A certain service co-production is needed to solve customers or users’ problems (Sundbo, 1991; Gallouj and Weinstein, 1997; Miles and Boden, 2000).

According to the service literature, the more interactive the co-production is, the better the solution can be. In a highly knowledge-intensive service, like a consultancy service, or in a basic hotel service, the interaction between users and providers is necessary for service delivery and client satisfaction. Interaction and co-production cannot always be face-to-face. Remote and online interactions can be services, but not connections per se, because authentic human encounters occur in human interactions. Even some self-service activities, like reading a book or watching a movie, can be channels of human service encounters between the users and the human stories, intentions, authors, producers, and characters of the books and movies (notwithstanding the argument that the authentically human interactions in which service encounters occur when seeing a movie are: going to the movie theatre, purchasing tickets, buying snacks, finding a seat, watching the movie, finding one’s way to the bathroom or the exit, and getting home).

The co-productive character of services connects to experience in the sense that the people using services (customers, clients, users) have different needs so they can co-create or socially co-construct a certain experience from the service in which they participate. An experience is a mental phenomenon that does not concern physical needs or solving material or intellectual problems as services do (Sundbo and Sørensen, 2013), but services generate experiences (Sundbo, 2015c). These authors also note a very interesting semantic issue: the concept of “experience” means different things in different languages. For example, the German word erlebnis—the most accepted one when talking about experience —denotes an “expressive” sense of experience, with connotations of 20amusement, escapism and the hedonic. However, the word erfahrung in German denotes a second “instrumental” sense of experience that evokes learning. Although the first meaning is more adequate to understand the experience economy (Sundbo et al., 2013), the second could also be useful in applying the experience concept into the business-to-business service economy. The second meaning is also useful when considering certain social aspects of experience. While erlebnis refers to individual experiences, erfahrung refers to more social experiences, such as learning from others. The distinction is subtle: even solitary individual experiences have a social character, and social experiences are aggregates of individual experiences in a community or organisation. In some cases, the expressive sense of experience may carry with it a sense of learning. For example, many varieties of philosophical and religious thinking—around the globe and throughout history—have encouraged reflection, an assessment to promote learning and growth (Giussani, 2006).

Current societal challenges and social developments are transforming the service economy, leading to new types of service experiences. Services are becoming more social and social (global to local) factors are increasingly influencing experiences, till the point that social considerations may determine whether an event is an experience or has any value. Pine and Gilmore (1999) noted that the experience of drinking a $5 coffee in a Starbucks coffee bar can provide about $4 of the value. The traditional goods and services economic factors—the cost of beans, coffee distribution, and service—amount to only $1. The social reputation of the coffee place—rather than its intrinsic characteristics—accounts for most of the $4 value added. Fancy coffee places are not always the most reputed ones in terms of quality of the coffee, and the role of others contributes to the individual value of the service experience —often a social experience involving a local or like-minded community frequenting the coffee bar.

Social preferences and values have shaped preferences and values in small communities since the beginning of human history. Now, in the age of globalisation, universal social values and preferences—globally shared via the Internet and other media—condition many emotions evoked by leisure, amusement, escape, art, fashion, and design. People follow others: all likes and dislikes in social networks create a certain idea of what an experience should be, something others may like, something for which others can accept and value an individual. In the 21coming years, new services and service innovations will increasingly converge on this alignment between individual likes and social approbation. People also want to be exclusive and separate from others, so service innovation will increase the need to be unique and enjoy unique service. In both cases—being a follower or being a unique, innovative leader-seeker—others are influencing each person’s individual preferences and mindsets for experiencing services.

2. The social character of services

Traditionally, economists have approached services from a sectoral view, defining services as a tertiary (as opposed to primary or secondary) sector. Some are business activities, some public services, some third sector and social initiatives, but all are services. The sector-based approach to services was concomitant with the identification of some distinguishing characteristics retaining certain negativity when they were defined by what they are not (non-material, non-durable, non-storable, non-transportable, non-accumulative, etc.), even if it has long time since these negative characteristics were criticised (e.g., O’farrell and Hitchens, 2016). Hill’s well-known article ‘On goods and services’ (1977) was a pioneering step toward a positive approach. He put forward the first positive difference between goods and services: goods are physical objects that are appropriated and are therefore transferable between economic units. However, services provided by one economic unit change the condition of persons or goods belonging to other economic units. Hence, services intrinsically have a social character. Men and women living in a society change other economic units. Therefore, economists now define services as results of co-production between service providers and users. Services always involve two or more people, agents, or organisations.

This approach to services has also led to showing the essential role of services in all kinds of other sectors and activities. The idea that services are modern activities—whereas agriculture and manufacturing were the historical sources of wealth—is still popular. Nothing could be further from the truth: services were born with humanity. Although 22the harvesting and hunting activities of the first hominids fall within the primary sector, people living then would have understood these activities as services performed by some members to help the community to which they belonged and expected others to reciprocate with services such as childrearing, healing, and producing essential crafts. All economic production becomes a service to the extent that it is not the result of a mechanical, pre-established, or instinctive process. Animals also try to satisfy their needs with limited resources. However, humans adopt a progressive awareness of the resources available and, by discovering original solutions, find the means to make the most of the available resources in a non-predetermined way; creative intelligence applies. In their search for satisfaction, humans retain a conscious relationship with their desires and needs (some of which remain unfulfilled), and with opportunities for satisfying these through human work. Human awareness of reality encourages a responsibility toward working in society at a level of complexity and interaction communities of ants, bees, lions, and dolphins do not share. The main human activity consists of a jointly responsible working activity in the interests of the common weal. War, robbery, or pilferage are ways to accumulate wealth, but all are contrary to the sustainable development of a community. As humans consider their dominant position, they perceive the possibility of constructing a stable and peaceful society through work. Although this is not always the case, humans know that violent conflict in the fight for survival may be inevitable sometimes, but is not sustainable nor necessary to manage scarce resources. Intelligence and self-awareness allow humans the corresponding understanding of their activities. Human action, especially work, generates a service to the whole society. The service has a teleological social character of joint responsibility in the workplace: one works “toward” rendering a service with an end product, cause or need, and one works “toward” providing the service to a person, family, or community.

Joint responsibility connected to services stems from the etymological sense of the term “service,” which in turn stems from the Latin servitium (slavery) and servus (slave). Historically, hierarchical social relationships (e.g., master and servant, slave and lord) later extended to military, royal and governmental services. Services progressively emerged from within a private sphere to wider social spheres. The extension of this trend suggests that, in democracies, political authorities work (at least 23theoretically) for the service of society. Therefore, services become the means and ends of political action, too. Similar parallels occur with any economic activity: enterprises work in the service of the existing or created needs of consumers. Even goods themselves produce a service (i.e., the value of the goods, the value of a car is the transport service it produces). This is the key idea behind the service-dominant logic (SDL) at the basis of the consumption theory in economics developed long ago (Lancaster, 1966; Becker, 1974): humans apply their competences to benefit others and reciprocally benefit from others’ applied competences through service-for-service exchange (Vargo and Lusch, 2004), which can be extended to the entire economy. SDL regards all goods and economic activities as services. This is true but not necessarily the whole truth. Services are also distinctive activities independent from goods. Services—even services connected to and packaged with goods—have their own characteristics and dynamics. The service economy, beyond the ancient “servitium” concept, has an intrinsic social character (co-producing with others) that differs from the service element of goods (creating products for others). Services are not commodities; they are the outcomes of human interactions. Therefore, because humans live in society, services are outcomes of social encounters. This explains how service innovation is approached in the literature from multiagent context perspectives (Gallouj and Weinstein, 1997; Windrum and Garcia-Goni, 2008).

The multiagent framework for service innovation can also be useful to understand social innovation in services. Social innovation is an emerging research area defined by social goals and social means (Pol and Ville, 2009; Hubert, 2010; Van Der Have and Rubalcaba, 2016) that also occur in services (Windrum et al., 2016).

3. The social character of experience

Experiences have been considered solipsistic: they are purely individual, not social. Sundbo and Sørensen (2013) define experience as mental impact, caused by personal perceptions of external stimuli, that an individual feels and remembers. This is highly based on the 24concept of the experience economy related to the experience sector and experience industries: activities that aim to deliver elements that can provoke experiences in people who pay for them directly or indirectly (Sundbo and Sørensen, 2013). However, although experience is an individual concept related to mental processes and emotions, the social is also there. Again, Sundbo and Sørensen (2013) give the example of cave painting 14,000 years ago illustrating the experience that cavemen could have had when viewing them. Many of those paintings depict social actors (for example, in hunting scenes involving a social event). The mere existence of the painting is also the outcome of a social community life. The production of art (or any service) involves others creating or co-producing those services. In a world where global telecommunications networks, social networks, and cultural globalisation promote billions of knowledge, artistic and entertainment experiences every day, the possibilities of experience achievements are more than ever related to social dynamics. In the XXI century, global social experiences shape individual experiences more than ever. All experiences have a social character; no experiences are solipsistic. The concept of experience can extend from individual experience (mental impact on a single individual) to social experience (collective mental impact on a business or community, as a sort of aggregation of similar individual mental changes). This happens when social innovation is approached through the social learning concept associated with collective actions (Hamdouch et al., 2013).

Individual and social experiences can be concomitant. A football match is a good example of this alignment between individual and social experience: the individual experience of enjoying the match in the stadium can align with the social goals of others attending, the players and the clubs. Achieving social goals may require adjusting individual attitudes: a team may win more easily insofar as its fans support it. Examples also abound in market and business services, where actors and values are obviously different, but business experiences have a social character too.

Social charitable services from NGOs are the best examples of how much alignment is possible between individual goals and experiences and social goals and experiences. When, for example, volunteers work for free to offer charitable services to the poor, the volunteers share, to 25a certain extent, the condition of those receiving the services: their time is mostly non-paid. Like the extreme example of service co-production with social ends: to interact with the poor or socially excluded people, volunteers share their goal of welfare by adopting a unique co-productive milieu for a service experience on both sides. The experience of working for free in front-line with the poor create the right atmosphere to co-produce the charitable service. Social and individual goals and social and individual means can be paradigmatically aligned in this example of charitable services.

4. Services, experiences, and innovation

Looking at new or improved goods that are partly based on or generate service innovation helps show the relationship between services, experiences, and innovation. A car is useful for the transportation service that the driver (not the car itself, at least not yet) produces, and service innovations are improvements to the characteristics of such services (such as speed, design, security, or communication). A new or improved aspect of the car changes not only the transportation service it provides but also the driving experience itself. Service innovations do not merely improve existing service characteristics (such as speed, design, or security). Sometimes, service innovations add new characteristics that did not exist previously (e.g., the adoption of the GPS allowing drivers to take the shortest route by getting directions in real time). Another way to add service is to include in the “car package” other pure services such as maintenance, funding, etc. The new combined package of the good and related services leads to a new experience. The more interactions a service involves, the more diverse the experiences can be. We could call some “service experiences.”

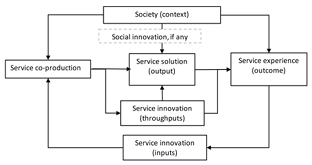

Service experiences are the outcomes of service co-productions that have produced a solution or output. (In a wide sense of the word “solution,” a museum allowing patrons to view paintings is a service solution to the human need for beauty or novelty.) Innovation changes or improves the service, leading to new experiences. And the experience provides 26inputs for future service innovation processes. In this view, innovation can reinforce the linkage between service co-production and service experience, but it can also facilitate innovative co-production (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 – Relationship between services, experience and innovation.

Figure 1 also places the role of society and social innovation in the relationship between services and service experience. All service co-productions and service experiences take place in a social context. Sometimes, social innovation occurs.

The relationship between services and experience can also be understood in the debate over whether services and experiences are independent phenomena or whether they are parts of all economic activities (Sundbo, 2015c). Considered as independent phenomena, services are deliveries under some activities and sectors—having quality, interactions and co-productions are key aspects—while experiences come from the activities making mental impacts possible (from creative services or other services provoking impacts on users). Considered as parts of all economic activities, by contrast, services are parts of all products and productive activities within every economic sector (Rubalcaba et al., 2012), while experiences are related to the satisfaction that makes customers buy a product or service, as proposed by the SDL theories (Vargo and Lusch, 2008).

Diverse types of experiences have services-related activities. Sundbo (2015a; c) and Sundbo and Sørensen (2013) report several types:

27–hedonic (entertainment, aesthetic, joy, and amusement) vs optical-moral (social consciousness, existential meaning creation) vs intellectual (learning)

–active from people seeking experiences provoking stimuli (people attending a concert or a match) or passive receiving external stimuli (people watching concerts or matches from their places)

–absorptive (bringing the experience into the receiver’s mind as in entertaining and teaching) or immersive (digging deep into the experience like when experiencing nature or reading a book).

These typologies are for classifying individual experiences, mostly hedonic or cultural services, many of them self-services. However, some also apply to company experiences. Companies may be passive or active in managing the information and knowledge they have, they can also try to absorb the knowledge provided by consultancy services or immerse in the knowledge and experiences employees have and interrelationships with providers and clients. Therefore, companies do not deliver experiences by themselves but may procure certain social-intellectual or social-capital-based experiences for their workers by, let us say, promoting interactions between the in-house business environment and the external business milieu (e.g., activities related to learning, sharing, and mutual learning).

Sundbo (2015c) identified three roles for experience in the service literature: (i) phenomenological (how services are experienced in groups), (ii) architectural composition of service actions, and (iii) positivistic in nature (meaning the outcome). Most of the literature about these types of understanding experiences in services refers to service marketing and service management. Sundbo’s (2015b) theory focus model identifies the move from instrumental service products and expressive service marketing toward experience hedonic products and experience ethical learning products. Non-profits may also derive social experiences in a different social context.

Similar or identical stimuli or circumstances may lead to very different impacts in people, companies, or organisations. The same concert may create huge positive experiences for some participants, negative experiences for others, or none at all for unconscious or sleeping attendees. The same consultancy advice may create a huge positive impact for some companies, none or negative for others. This is because purely objective external factors (such as the music performed at the concert or the advice 28the consultancy provides) do not determine the experience. Internal factors (such as the concertgoer’s mental state or the client’s corporate culture) matter, as do factors related to the interactions between the internal and the external (for example, whether the music causes a headache, or the client rejects the consulting advice rather than internalises it). These factors can help us understand why some experiences are more or less positive, and how service innovations try to make all the experiences more positive, for which the social plays a role.

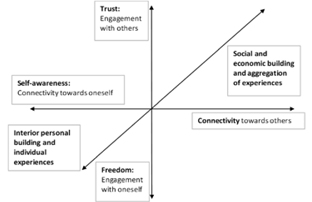

Figure 2 depicts a model where services co-production happens in connection with the experiences services can produce. The model has two dimensions: connectivity and engagement. The connectivity dimension ranges from connectivity with others (connection experiences) to connectivity with oneself through self-awareness (introspective experiences). The engagement dimension ranges from engagement with others through trust (communal experiences) to engagement with one’s own preferences through freedom to choose (freedom experiences). The combination of the two dimensions explains how social experience is possible through aggregation of experiences.

Fig. 2 – Two-dimensional model for services co-production

and experiences for individuals and society.

Connectivity. People, companies, and organisations enjoy or facilitate service experiences by connecting with others. Merely being connected can also be an experience. The users and the providers of a service always connect in some fashion. Often, users do not seek a connection to the provider. Rather, users anticipate receiving a connection to the whole world through the provider. The service becomes instrumental to a connection to the world in the hope that the connection will cause an experience (for an individual) or business benefit (for a company), not necessarily a service experience. Open innovation in services (Chesbrough, 2010) and user-driven innovation (Sundbo and Toivonen, 2011) are related to a sort of new business experience after the co-production of some innovation activities with the clients. Innovation in services reinforces connectivity as one of its main characteristics: it gives content to information and communication tools like the Internet. Online social networks, for example, are a paradigmatic example of connectivity instruments to develop service innovation by offering new possibilities for new experiences. The more open to the world people are, the more service innovations can facilitate their having better and more novel experiences. Services associated with transport and driving activities are powerful examples. Based on social innovation, people using the same app (e.g., Waze) can communicate about how drivers nearby are doing, find the fastest routes to get to a destination, and get feedback when, for example, they are exceeding posted speed limits. A driver can also improve the driving experiences of others by sharing information about crashes, closed roads, hidden police, and so on. The result is not only a new driving tool but also a novel connectivity-based experience based on social engagement around a service innovation, a new interactive GPS-based app.

Self-awareness. Connectivity with others is a source of service innovation, but connectivity with oneself is another source. It is particularly powerful in services related to religious activities, mindfulness and relaxation services, and social and non-profit -sector work. All services have a social power to increase a person’s self-awareness, including who the person is, where the person is, and what the person wants in life. Leisure and culture experiences can also be a way to escape from the daily routine. Sometimes, they also improve a person’s ability to undertake daily routines in a better way. In a service relationship, self-awareness is possible due to interactions between the oneself and others. Like one post 30in a social network receiving a lot of likes or dislikes, it is a way to know better what works and what does not work in a social context. Companies themselves also need some self-awareness (inside the company culture) of their own position in the markets, and business services are highly useful in getting improving self-awareness. Service innovations can increase self-awareness, both for individuals and for businesses and other collectives. Religious services for believers, travel services for tourists, and strategic advisory services for companies can increase self-awareness by providing better knowledge of how the own positioning and integration works, in a dialogic way —co-produced with services providers—. Services improve understanding by increasing knowledge or information about where one fits in society. This services-effect is also true of the linkage between expressive experience and instrumental or learning experience. Finally, some services can increase both connectivity with others and connectivity with oneself. Services related to religious activities can contribute to self-awareness, but connecting with others is also an important element deeply linked to transcendental connectivity (connectivity with God).

Trust. Service co-productions are impossible without trust. Customers trust retailers to provide fresh food, telecom companies to provide reliable services, and gym trainers to design healthy workouts. Companies trust knowledge-intensive business services when contracting new service design or business restructuring. Patients trust doctors when going into surgery. Parents trust teachers when sending their kids to school. Trust is essential in any economic activity. However, in services, trust is not just a one-time thing, like when buying a good. Instead, the entire co-production requires trust. Therefore, there are many moral hazards and adverse selection issues in services. Information in services is much less complete and more limited than information in goods. The experience of trust relates to the experience of something good coming from another. When a buyer trusts the provider of a service, the buyer implicitly assumes there is something good behind that provider. The another is a good for the people coming into the services game, it can bring something good, beyond the many circumstances from which mistrust can emerge. Living in a services society is living in a world where people can expect good things from others, in a co-productive service, which requires mental openness: services suppliers, service workers or services users are a source for growth and experience if distrust prevails. Building walls inhibits the growth of services. In a 31trusting context, services are innovative and build toward joint achievements. Successful services build social links and make societies stronger.

The experience of freedom. Trust and co-responsibility are intangibles essential for developing free interactions in the service economy. Clients and suppliers must use their freedoms to act together, assume the risks, and develop something new, a service able to satisfy a need. Freedom to choose the right co-producer with whom to work (trust) and freedom to put the right efforts in the common project (co-responsibility). All characteristics of positive services link to freedom. Freedom is at the basis of service development, once there is motivation to have a service and start a co-production process. Having a deal with someone, interacting, achieving the expected result, and obtaining the related satisfaction all require freedom. (Freedom may also exist in a prison given this concept of freedom). Freedom itself can be conducive to a service experience, as when leisure and creative services give a feeling of choosing (fewer choices can be better than many choices) in a world in which people do not choose most routine activities. Providing choices is a way to increase a certain service experience in a social context. In this context, the state must guarantee conditions that favour free interactions and movements for services, in society and markets. For example, allowing people to work and live to/from other countries and a way to increase freedom to choose both for service workers and for the service users.

The four experiences related to service innovations (connectivity, self-awareness, trust, and freedom) are all behind different concrete experiences in business services, cultural services, leisure services and so on. For example, a tourist arriving in a new destination can have a service experience by interacting with local people and communities (connectivity), by relaxing during the vacation (because of trusting people, food, security), by having the choice to decide on his/her own places to eat, to visit, to sleep, etc. (freedom) and by finding a better way to understand the sense of his life and actions in the global world (self-awareness). In this context, innovation adds or changes characteristics of the tourism service by changing conditions (e.g., an unexplored route, an encounter with new local dancers or musicians, novel service amenities in the hotel) that will lead to a different experience or improve earlier service experiences.

Educational services are another good example of the utility of this framework. Table 1 illustrates how innovations in education generate 32new experiences. For understanding this, our two-dimensional model of service co-production is also useful. Along the connectivity dimension, innovation in education promotes connectivity to others—the experience of connecting with teachers, classmates, communities, and societies. Education also connects oneself through both expressive experiences and intellectual learning experiences, allowing a better awareness of one’s own skills, abilities, and personality. Service experiences build character. For this to happen, engagement through trust in the learning community becomes the natural milieu for school immersion. This community may even ease social inclusion, as in inclusive and comprehensive schools. Choosing schools that provide the most autonomy can align trust-based engagement with the freedom experience. In education, the “I” and the “others,” connectivity to others and to myself, trust, and freedom, grow together in a social environment in which conflicts and negative experiences should always be the exception and not the rule.

|

Category |

Examples |

|

Connectivity experiences |

–Following standard learning (being part of a common experience) vs distinctive education (being exclusive) –e-Learning (IT distance learning experience) |

|

Self-awareness experiences |

–Character building –Promotion of own skills and gifts (e.g., experiences related to artistic, musical, or athletic achievements) |

|

Trust experiences |

–Learning community –Inclusive and comprehensive school (inclusion experience) –Tutoring (teacher-pupil experience) |

|

Freedom experiences |

–School choice and autonomy in management and teaching (flexibility experience) –Alignment with own values experience –Home-schooling (experiences from new balances between schooling and home-based learning) |

Tab. 1 – Categories of service experiences in education

and examples related to service innovation.

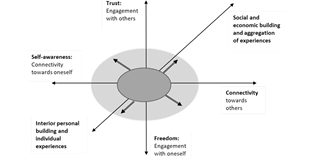

Taken together, the two dimensions (connectivity and engagement) explain not only how interior building (self-character progress) is possible with the benefit of individual experiences, and how social and economic building (economic and social growth) is possible through aggregation of experiences, but also the overall development of a services economy in a service environment (a company, a household, an institution, a city, a region, or a country). The more that co-producers create individual and social engagement, and the more they achieve individual and social connectivity, the more developed a service economy may be, at the heart of the integration between the individual experience-based performance and societal performance. A little development of a service economy would mean little connectivity and little engagement. Figure 3 represents this with a small circle spanning both dimensions (Figure 3), while development of the service economy would lead to a wider circle because of complementary effects between the two poles of a single dimension. (For example, more connectivity with others may reinforce self-awareness and introspection). This possible complementary does not preclude the existence of substitution effects in each dimension (e.g., high connectivity with others through social networks often plays against self-awareness and connection with oneself). Despite trade-offs on both engagement and connectivity, the development of the service economy corresponds with the expansion of aligned individual and societal experiences.

Fig. 3 – The development of the service economy

when individual and societal experiences align.

Individual and social experiences may not align. A service economy may also move against the interest of part of the service users, or the dominant experiences of a minority may conflict with the experience of a majority. In these cases, there is no alignment and the social building is not a bottom-up aggregating experience but a top-down one. This could lead to many different frameworks depending on the different dynamics of service systems, institutional arrangements, social contracts, and political regimes.

5. A five-faceted, ten-dimensional model

for understanding new trends

in service innovation

Service innovation has evolved to accommodate human contradictions. Sometimes we must be alone; sometimes we must be with others. Sometimes we must do things for others; sometimes we must do things for ourselves. Sometimes we must experience something novel or different from what others experience; sometimes we must repeat a comfortable experience or follow what others do.

Overall, however, service innovation is becoming more open and more social. Helped by ICT, the links formed between companies or organisations and consumers or users to co-produce services interact more and more with a whole range of institutions, social actors, and social networks. Service innovation becomes social innovation when multiagent frameworks apply and bilateral co-productions transform into multilateral ones. This section proposes a model for understanding transformations related to these new service innovation dynamics.

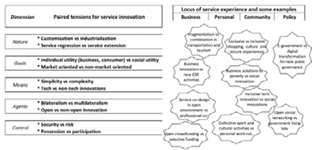

The model has developed out of the observation that services innovation is evolving based on the interplay among many tensions. Trends in services innovation are related to tensions in service design and provision. Gallouj et al. (2015) identified four trends related to the nature of services. Two arose from a pair of tensions: the tension between customisation and industrialisation and the tension between services regression and services extension.

35This section identifies tensions along pairs of dimensions related to four additional facets of services innovation. The full model, illustrated in Table 2, thus encompasses five facets of services innovation. The facets are: (i) the nature of the services innovation, (ii) the goals of the services innovation, (iii) the means by which participants achieve the services innovation, (iv) the agents who participate in the services innovation, and (v) how they control the innovation. Each facet has two dimensions. Each dimension embodies a tension between two poles. Each point of equilibrium, or balance, between the poles on a dimension is unique. Thus, every overall equilibrium balancing tensions across all five facets and ten dimensions represents a potential development in service innovation that could produce different service solutions; some would produce different experiences in users.

|

Facet |

Dimensions (tensions driving service innovation) |

Ongoing trends |

|

Nature |

Customisation vs industrialisation Service regression vs service extension |

More diversity |

|

Goals |

Individual utility vs social utility Market-oriented vs non-market-oriented |

More societal |

|

Means |

Simplicity vs complexity Tech vs non-tech innovations |

More co-production ways |

|

Agents |

Bilateralism vs multilateralism Open vs non-open innovation |

More multiagent |

|

Control |

Security vs risk Possession vs participation |

More trust needed |

Tab. 2 – The five-faceted, ten-dimensional tension model

for understanding service innovation dynamics.

Tensions along most of the ten dimensions are driving services innovation to be more social and open. Globalisation and ICT are changing the nature, goals, and means of services, transforming the service innovation landscape. The model provides a conceptual framework to understand transformations behind service innovation dynamics.

36Further, tensions along all ten dimensions have consequences for service experience at four loci: personal experience, business experience, community experience, and policy experience. Although the concept of experience has traditionally applied only to individual consumers and users, experiences can also be collective and be incorporated in local communities and organisations such as firms and public administrations. Figure 4 provides examples. The social element is present in all these tensions.

Fig. 4 – Tensions on services innovation with some examples.

5.1 Tensions related to the nature of services

innovation: industrialisation versus

customisation and service regression

versus service extension

Gallouj et al. (2015) describe two major dimensions explaining emerging trends in services innovation. We refer to them here as the bespoke dimension and the value dimension. The bespoke dimension embodies the tension between industrialisation and customisation of services. It derives from the recognised tension (Gallouj, 2002; Rubalcaba, 2007) between highly-personalised services (such as KIBS) and highly-standardised services (such as transport). This tension arises from the different needs of supply and demand in co-production. Companies try to standardise their services to pursue a variety of advantages and profit from economies of scale. In contrast with suppliers, many customers want 37precisely the opposite— personalised services catered to their needs. This trend has increased the number of KIBS companies offering specialised advice, tourism companies offering personalised travel adventures, and companies offering very exclusive shopping, cultural experiences, or leisure activities. Reconciliation between these two extremes—bespoke services delivered according to rigorous standards—is new and creating innovations. Examples include (i) retailers offering increasingly personal adaptations in large surfaces and hypermarkets, (ii) consultancies offering tailored advice using standard methodologies, and (iii) schools offering personalised education and even support for home-schooling to provide the best of both school and home worlds. The success of this reconciliation relies on building a new experience combining the best of the elements of opposite experiences (e.g., the best of the adapted curricula in education with the best of social life at schools).

A similar evolution is also happening in the value dimension, the second tension that Gallouj et al. (2015) describe related to the possible range of services. The value dimension embodies the tension between generating basic services (service regression) and generating services that add more value (service extension). Low-cost business models in tourism, retail, transportation, and restaurants are examples of services regression: providing basic services cheaper. Service extensions occur when service providers add new elements to basic services. As examples, hospitals might offer non-medical health services (e.g., fitness, wellbeing) services to their patients or real estate services companies might offer new pre-sale, at-sale and after-sale services (such as inspection, remediation, and furnishing services) to their clients. Here, reconciliation is happening through a la carte menus where users can choose between basic services or value-added services in the same restaurant, school, trip, and so on. This reconciliation is generating innovation in traditional companies facing competition from low-cost companies.

5.2 Tensions related to the goals of services

innovation: individual versus social utility

and market versus non-market orientation

The goals of services innovation have two dimensions: utility and orientation. The utility dimension embodies the tension between maximising individual utilities and maximising social utility. Individual 38utilities include business goals and profits (for firms) and satisfaction of personal utility goals (for individuals). Social utility includes satisfying social goals that can be pursued not only by NGOs and the third sector but also by public administrations and even companies. For-profit companies work for economic benefits but can also work for social goals, such as when they develop CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) programmes or integrate social goals into their primary business strategy. In these cases, it is possible to reconcile business and social goals.

The orientation dimension embodies the tension between market orientation and non-market orientation. The tension of the locus of service delivery complements the tension on the goals. It can be a market or a non-market place. For example, social activities for fighting poverty can have business goals and operate in markets (as when promoting inclusive innovation with low-cost technology), or they can have social goals and operate outside the market. Social innovation supported by the third sector, local communities, and public administration promote these sorts of non-market activities.

5.3. Tensions related to the means of services

innovation: simplicity versus complexity

and technological versus

non-technological innovation

Barcet (1991) introduced the idea of covalence to capture the growing complexity of service relationships. This derives from the notion of covalence in chemistry, which describes the properties of atoms or ions that enable combinations or chains whose properties are determined by their constituent elements; independent of their nature, each has an essential place. From this idea, Barcet first deduced that different acts contribute to services. Another fundamental deduction is that services change when their facets change. Interactions between agents define systems of relationships that change in nature when new elements enter the system. Such open systems are natural consequences of covalence: supply and demand constitute a double-linked service within an environment or system from which co-production emerges, and whose nature changes with the introduction of any new element. In this context, service innovation often derives from new services and new related experiences. The simple traditional health services that a doctor provides a patient can radically change as technology allows the doctor 39to include other doctors in the room, share opinions, and provide more comprehensive and accurate services. Expanding the available expertise increases the feeling of certainty in the patient when receiving a diagnosis and treatment plan. This tension is partly related to the tension between regression and extension on the value dimension. Simplicity is often the way to regress to basic services, whereas services that add more value often require more complexity.

The tension between technological innovation and non-technological innovation often interacts with the tension between simplicity and complexity. Technology can simplify or complicate a service. As the Internet makes travel easier, it can also complicate the experience of shopping where multiple alternatives exist, or, for the consultant, the expertise of selecting the relevant information in an overinformed area. Besides, technological innovation often requires non-technological innovation. One example is the development of water purifiers for India, which US research institutes largely funded. These purifiers were inclusive technological innovations, but they faced the problem of how to distribute the water from the purifiers to the population, often in remote rural areas. Empowering local communities to arrange water distribution systems from the purifiers to the homes required non-technological service innovations that provided social innovation experiences for the communities so that they could take advantage of the technological innovations. However, technological and non-technological innovations are not always in sync. For some time, the purifiers were underused because of the dearth of non-technological innovation.

5.4. Tensions related to the agents of services

innovation: bilateral versus multilateral

and openness versus closeness

The agents facet of services innovation has two dimensions. One dimension embodies the tension between bilateralism and multilateralism, the other the tension between openness and closeness. They are related, but it is possible to have both few agents in an open interaction and closed multiagent interactions. Goods consumption is often bilateral between a provider of goods (the maker or seller) and a customer (individual or firm). Service production and consumption can also be bilateral (e.g., hairdressing or tutoring) but they are often multilateral. Multiagent 40contexts are not necessarily multilateral. Although firms have relationships with many clients (some may have millions of clients), the relationships are mainly bilateral (between clients and the company). They can even open the innovation department to their clients (clients develop new products like in the famous case of Lego). However, both the services and interactions for innovation can remain bilateral (client-company). The alternative is, for example, to allow open engagement where social networks can expose innovation ideas for co-design, and launch new communities so clients can also interact among themselves. Another example (Gallouj et al., 2013) is private-public-third sector networks in services (ServPPINs), some of which are social innovations. These cases involve a multiagent configuration, so multilateralism is critical for developing service innovation. However, in most cases, the approach is professional and restrictive to the partners, so they are not examples of social innovation unless third sector organisations are partners that represent the final users and serve as focal points for interactions between the ServPPIN and the final users. The tension drive service innovation toward more multilateral and social relationships is related to the move of services innovation toward more social innovation, with linkages with system innovations. Researchers (e.g., Djellal and Gallouj, 2012; Windrum et al., 2016) have already examined the bridge between service innovation and social innovation from a systemic/multiagent perspective.

5.5 Tensions related to the control of services

innovation: security versus risk

and possession versus participation

Finally, the control facet of services innovation and its related experiences has two dimensions: control of the expected result (embodying the tension between security vs risk) and control of the expected interaction (embodying the tension between possession vs participation). The perception of risk with services—arising from their co-productive and covalent character—differs from the perception of risk with goods. When consumers purchase goods, guarantees, endorsements, standards, repair services, and insurance reduce the risk inherent in the quality of the product. In some businesses, a simple statement from the client about perceived defects is enough to exchange the goods or return the money. The process is different in services. First, the risk connected 41to purchasing the service does not have as many mechanisms for risk reduction. It is not possible to return a service consumed during production. However, services have processes for endorsements, standards, and accreditation that go much further than the processes for goods. Such assessment and accountability safeguards with the aim of bolstering security and reducing risk are particularly evident in education. However, assessments often undermine innovation in education (Looney, 2009), so systems are forced to assume pro-innovation risks, as in US charter schools (Lubienski, 2009).

The second dimension of control embodies the human tension between controlling service interactions (possessing process and result) and participating in something that is not under control. A football fan, for example, has a choice of experiences. One option is to watch a match from home, with easy control of breaks, volume, replays, incoming calls, friendly people with whom to watch the match, and so on. An alternative is to participate in the match at the stadium, where none of those factors are easy to control, and the experience is consequently different. This tension between control and participation is unique to the service economy.

The potential of goods is fixed a priori. The value of using goods depends on how long one uses them and how one judges the results. (Purchasing a car—which can work out well or badly—is an example.) Goods contain their potential at the time of purchase. (The car is good or bad.) Consumption of a service always has a counterpart, which prevents applying the same reasoning as with the consumption of goods. With services, it is essential to create a fruitful relationship that cannot be pre-established. The potential development of this relationship unfolds over time; it is not fixed at the time of purchase or contracting but verified according to the knowledge and ability that the parties apply in co-production. In this sense, services are ephemeral because they change when faced with new phenomena (as deduced above regarding covalence), whereas goods, by nature, do not change unless a radical transformation or dilapidation of goods is carried out consciously after purchase. Services unfold their hidden potential at the point of the first co-productive act, whereas a predetermined potential unfolds in goods. What remains hidden in the potential of the service always supersedes what is revealed while it becomes an act. Due to this 42dynamic unfolding, service experiences can vary widely depending on the user, the conditions, the motivations, the preferences, and so on. Expectations can be very different.

The outcomes of service innovation are different experiences. These are usually based not on single tensions but on combinations. An example from education can illustrate this point.

6. The case of education services

illustrating service innovation

tensions and experiences

A participatory logic prevails in educational services, even if standardisation can reduce the level of co-production. A real education will always require customisation and co-production. Besides, the social component in education is often recognised and has anthropological roots. Education requires the right family and cultural environments. Lousy family or cultural climates are obstacles to education because students are never islands. Instead, they are human beings participating in society. The deeper the awareness about the importance of education in society, the higher the desire to educate not only in cognitive skills but in behavioural, social skills too. The role of society in the act of education is therefore both at the origin of education (we all are social beings) and at the ends (we need education to be, live and work in society).

In a relationship between a teacher and a student—the most importation relationship in education—these concepts are fundamental to delivering high-quality service, which often translates into high-impact experience. A teacher and a student share the same humanity, desire, and heart, so there is the basis to start a fruitful relationship and build a learning community. However, what hides in each part is more important and dynamic than what is revealed in a moment. The process of education is a process of simultaneously discovering both reality and the one’s humanity. Openness to the other (the teacher, the student) and mutual interest are essential to both a genuinely co-produced service experience and a real education. Otherwise, only instruction and 43training remain, neither real education nor a real co-produced service. What is valid for a single teacher-student relationship is also valid for the full set of agents participating in education. Genuinely social participation is involved in co-producing education: parents are essential to a smooth teacher-student relationship, policymakers are essential to a smooth relationship between the schools, and so on. Each has a place in a participatory logic.

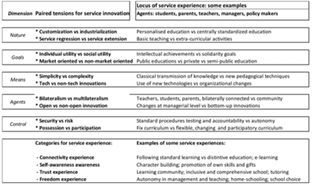

Figure 5 represents some educational areas and practices according to the five-faceted, ten-dimensional model of service innovation described in section 5. Innovation in education is diverse. Educational systems and institutions can promote a more customised education or a more standardised education, a more multilateral community framework or a more bilateral individual framework. Not all educational areas have a single location. For example, promoting autonomy for teachers (as in Finland where teachers must only follow certain guidelines) might maximise customisation to the needs of the class. However, it may not, and some teachers may promote more community-oriented education (reinforcing teamwork) while others may promote precisely the opposite by encouraging only individual effort. Each of the actions and areas proposed can lean more toward the social customised area or more toward the standardised and individualistic approach. The same applies to technology because some digital learning can be minimally customised (teacher-led courses) while others can be extensively customised such as in student-centric learning (Christensen et al., 2011), which is one of the most innovative and disruptive models.

Figure 5 also shows that educational services are more co-productive, interactive and multiagent than other services, unlike any good or a commodity. The choice between customisation and standardisation is a choice between dealing with education as a service (a result of co-produced learning) or as a commodity (that can be standardised and sold in the educational market or a political debate).

This context is also useful to understand two OECD works (Istance and Kools, 2013; OECD, 2013) describing innovative learning environments in the path from traditional education to contemporary pro-innovation and pro-customisation education. They state the need for a new individual and social balance. The traditional school was a combination of the social and individual: homogeneous ‘one-size-fits-all’ and whole-class 44teaching without collaboration with other learners or educators. The learning environments the OECD has examined have deliberately sought to rethink the stereotypical social and individual roles in ways relevant to the role of technology. These environments include “personalised learning” programmes that reject “one-size-fits-all” approaches. They provide rich mixes of small group activities, individual research and study, off-site and community work, virtual campuses and classrooms with communal teaching and learning. They promote openness to other stakeholders engaged in defining curricula, as sources of knowledge and as teachers. Finally, they embody a social understanding of learning, defined by “21st-century” content and competencies (OECD, 2013, p. 189). The OECD is moving toward the more multiagent, community, customised, and personalised poles of the tensions along the dimensions described in section 5. Paradoxically, however, some of the most technological innovations in education (like massive e-learning courses) have resulted from intensive efforts to standardise teaching (across thousands of students) in a highly individualised manner (online with no face-to-face interactions). Therefore, some new trends in education aim to create innovative learning environments not from real social and community perspectives but from virtual social and community perspectives.

Fig. 5 – Five facets and ten dimensions of innovation in education services.

45Finally, Figure 5 illustrates how innovations in education generate new experiences. For understanding this, our two-dimensional model of service co-production is also useful. Along the connectivity dimension, innovation in education promotes the experience of being connected to the teacher, the classmate, the school community, and the part of the society interacting with the school. Education also serves to connect to oneself through both expressive experiences and intellectual learning experiences, allowing a better awareness of their skills, capacities and personality. Students build character through service experiences. For character building, engagement through trust in the learning community becomes the natural milieu for school immersion. Engagement through trust may even facilitate social inclusion as in inclusive and comprehensive schools. Trust-based engagement can align with experiences of freedom by choosing the schools that provide the most autonomy. In education, the “I” and the “other,” connectivity to others and to oneself, trust and freedom, grow together in a social environment in which, as mentioned before, conflicts and negative experiences should always be the exception and not the rule.

7. Conclusion and final remarks

The co-productive character of services has its roots in the concept of the service encounter. Service encounters are not just human interactions. They produce solutions to problems and can also be instrumental to generate experiences in people, as ultimate outcome of a service co-production. Services do not operate on a bilateral basis isolated from the world, but in societies. Both service producers and consumers are highly influenced by others. Any service experience and any service innovation has an intrinsic social dimension that, sometimes, can also be delivered through social innovations.

Service experiences can be related to the connectivity and engagement dimensions in such a way that a priori antagonistic extremes (such as connectivity to others versus connection to oneself and engagement to others versus freedom to choose) can work in the same direction 46(substitution effects can be less important than complementary effects). Service encounters generate experiences in fruitful and positive relationships with others. (Mistrust and walls do not build the service economy.) Social relationships are at the nexus of service innovation and service experiences, and between the interior building of service experiences and the social construction of collective experiences. In a previous contribution (Rubalcaba, 2007), I defined the new services economy as the one in which services can be productive, tradable, and innovative on the one hand, and the one in which services are integrated in the entire economy, on the other. Now I would add that the new service “experience” economy is the one in which personal and community service experiences are the heart of socioeconomic growth and development.

This article has also shown how society determines the way that tensions related to service innovation develop (how, for example, services move between standardisation and personalisation, or how business goals align with social goals). Differing equilibria among tensions on dimensions related to the nature, goals, means, agents and control of service innovations result in different experiences spanning individuals, societies, and economies.

Perhaps this somewhat anthropological connection between personal services and society can be the most powerful contribution of the authentic service co-productive economy to sustainable growth and inclusion. Social building (i.e., combination of social and economic growth) is based on human interactions, some of which can lead to service trust-based co-production. Inclusive service co-production means inclusion for all types of others, from different cultures, countries, races and religions: this can be an opportunity for more services and more society (in the sense that individuals and groups can organise themselves to help each other), an experience economy where the human encounter is positive and leads to new and better services all the time. There are inevitably some bad examples in service innovation. For example, when there is too much technology in a human-intensive service, some innovations can lead to bad experiences in some sectors and contexts. However, most innovations, technological and non-technological, are designed and implemented to improve services and make them better for the world, as happens when innovations in educational services enhance the satisfaction and performance of both students and the entire community. The future of services needs positive innovations.

47References

Barcet A. (1991), “Production and Service Supply Structure: Temporality and Complementarity Relations”, in Daniels P.W. & Moulaert F. (eds.), The Changing Geography of Advanced Producer Services: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives, John Wiley & Sons Incorporated, p. 59-69.

Becker G.S. (1974), “A Theory of Social Interactions”, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 82, no 6, p. 1063-1093.

Chesbrough H. (2010), Open Services Innovation: Rethinking Your Business to Grow and Compete in a New Era, John Wiley & Sons.

Christensen C.M., Horn M.B. & Johnson C.W. (2011), Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns, Updated and expanded new edn, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Djellal F. & Gallouj F. (2012), “Social Innovation and Service Innovation”, in Franz H.W., Hochgerner J. & Howaldt J. (eds.), Challenge Social Innovation, Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer, p. 119-137.

Gadrey J. & Gallouj F. (1998), “The Provider-Customer Interface in Business and Professional Services”, Service Industries Journal, vol. 18, no 2, p. 1-15.

Gallouj F. & Weinstein O. (1997), “Innovation in Services”, Research policy, vol. 26, no 4-5, p. 537-556.

Gallouj F. (2002), Innovation in the Service Economy: The New Wealth of Nations, Edward Elgar Publishing, Chelthenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA.

Gallouj F., Weber K.M., Stare M. & Rubalcaba L. (2015), “The Futures of the Service Economy in Europe: A Foresight Analysis”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 94, p. 80-96.

Gallouj F.z., Rubalcaba L. & Windrum P. (2013), Public–Private Innovation Networks in Services, Edward Elgar Publishing, Chelthenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA.

Giussani L. (2006), The Journey to Truth Is an Experience, McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Gronroos C. (1990), “Relationship Approach to Marketing in Service Contexts: The Marketing and Organizational Behavior Interface”, Journal of Business Research, vol. 20, no 1, p. 3-11.

Hamdouch A., Moulaert F., MacCallum D. & Mehmood A., eds. (2013),The International Handbook on Social Innovation, Edward Elgar Publishing, Chelthenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA.

Hill T.P. (1977), “On Goods and Services”, Review of Income and Wealth, vol. 23, no 4, p. 315-338.

48Hubert A. (2010), “Empowering People, Driving Change: Social Innovation in the European Union”, Bureau of European Policy Advisors (BEPA).

Istance D. & Kools M. (2013), “OECD Work on Technology and Education: Innovative Learning Environments as an Integrating Framework”, European Journal of Education, vol. 48, no 1, p. 43-57.

Lancaster K.J. (1966), “A New Approach to Consumer Theory”, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 74, no 2, p. 132-157.

Looney J.W. (2009), “Assessment and Innovation in Education”, OECD Education Working Papers, no 24, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Lubienski C. (2009), “Do Quasi-Markets Foster Innovation in Education? A Comparative Perspective”, OECD Education Working Papers, no 25, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Miles I. & Boden M. (2000), “Introduction: Are Services Special?”, in Boden M. & Miles I. (eds.), Services and the Knowledge-Based Economy, London, Continuum, p. 1-20.

Normann R. (1991), Service Management: Strategy and Leadership in Service Business, 2nd edn, Wiley, Chichester, New York.

O’Farrell P.N. & Hitchens D.M.W.N. (2016), “Research Policy and Review 32. Producer Services and Regional Development: A Review of Some Major Conceptual Policy and Research Issues”, Environment and Planning A, vol. 22, no 9, p. 1141-1154.

OECD (2013), Innovative Learning Environments, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Pine B.J. & Gilmore J.H. (1999), The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage, Harvard Business Press.

Pol E. & Ville S. (2009), “Social Innovation: Buzz Word or Enduring Term?”, The Journal of Socio-Economics, vol. 38, no 6, p. 878-885.

Rubalcaba L. (2007), The New Service Economy: Challenges and Policy Implications for Europe, Edward Elgar Publishing, Chelthenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA.

Rubalcaba L., Michel S., Sundbo J., Brown S.W. & Reynoso J. (2012), “Shaping, Organizing, and Rethinking Service Innovation: A Multidimensional Framework”, Journal of Service Management, vol. 23, no 5, p. 696-715.

Rubalcaba L. (2016), “Social Innovation and Its Relationships with Service and System Innovations”, in Toivonen M. (ed.), Service Innovation. Novel Ways of Creating Value in Actor Systems, Translational Systems Sciences, Springer, p. 69-93.

Sundbo J. (1991), “Strategic Paradigms as a Frame of Explanation of Innovations: A Theoretical Synthesis”, Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, vol. 3, no 2, p. 159-173.

49Sundbo J. & Toivonen M. (2011), User-Based Innovation in Services, Edward Elgar Publishing, Chelthenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA.

Sundbo J. & Sørensen F., eds. (2013), Handbook on the Experience Economy, Edward Elgar Publishing, Chelthenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA.

Sundbo J., Sørensen F. & Fuglsang L. (2013), “Innovation in the Experience Sector”, in Sundbo J. & Sørensen F. (eds.), Handbook on the Experience Economy, Chelthenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA, Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 228-247.

Sundbo J. (2015a), “Experience Economy”, in Dahlgaard-Park S.-M. (ed.), The Sage Encyclopedia of Quality and the Service Economy, London, Sage, p. 219-223.

Sundbo J. (2015b), “From Service Quality to Experience – and Back Again?”, International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, vol. 7, no 1, p. 107-119.

Sundbo J. (2015c), “Service and Experience”, in Bryson J.R. & Daniels P.W. (eds.), Handbook of Service Business: Management, Marketing, Innovation and Internationalisation, Chelthenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA, Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 205-222.

Sundbo J., Sundbo D. & Henten A. (2015), “Service Encounters as Bases for Innovation”, The Service Industries Journal, vol. 35, no 5, p. 255-274.

van der Have R.P. & Rubalcaba L. (2016), “Social Innovation Research: An Emerging Area of Innovation Studies?”, Research Policy, vol. 45, no 9, p. 1923-1935.

Vargo S.L. & Lusch R.F. (2004), “Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing”, Journal of marketing, vol. 68, no 1, p. 1-17.

Vargo S.L. & Lusch R.F. (2008), “Service-Dominant Logic: Continuing the Evolution”, Journal of the Academy of marketing Science, vol. 36, no 1, p. 1-10.

Windrum P. & Garcia-Goni M. (2008), “A Neo-Schumpeterian Model of Health Services Innovation”, Research Policy, vol. 37, no 4, p. 649-672.

Windrum P., Schartinger D., Rubalcaba L., Gallouj F. & Toivonen M. (2016), “The Co-Creation of Multi-Agent Social Innovations”, European Journal of Innovation Management, vol. 19, no 2, p. 150-166.

1 The author is also grateful for comments from the reviewers and the editor and for suggestions from Aarre Laakso.