Explorer le stress professionnel dans le secteur suisse de la gestion de patrimoine Comment le risque humain peut-il conduire à une destruction de valeur ?

- Type de publication : Article de revue

- Revue : European Review of Service Economics and Management Revue européenne d’économie et management des services

2017 – 1, n° 3. varia - Auteurs : Dubosson (Magali), Fragnière (Emmanuel), Pasquier (Marilyne), Reynard (Cyrille)

- Résumé : Les processus de service doivent tenir compte du bien-être des employés pour créer de la valeur. L’article montre que le lien entre bien-être et création de valeur peut être aussi étudié sous l’angle de la gestion des risques. Une approche exploratoire permet de comprendre cette problématique au sein du secteur de la gestion de fortune à Genève. Sur cette base, le modèle créé part du mal-être pour aboutir à la destruction de valeur et inclut une boucle de rétroaction négative.

- Pages : 17 à 45

- Revue : Revue Européenne d’Économie et Management des Services

- Thème CLIL : 3306 -- SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES -- Économie de la mondialisation et du développement

- EAN : 9782406071204

- ISBN : 978-2-406-07120-4

- ISSN : 2555-0284

- DOI : 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-07120-4.p.0017

- Éditeur : Classiques Garnier

- Mise en ligne : 23/08/2017

- Périodicité : Semestrielle

- Langue : Anglais

- Mots-clés : Recherche ethnographique, mal-être, risque humain, processus de service, destruction de valeur

Exploring occupational stress

in the Swiss wealth management sector

How could human risk lead to value destruction

Magali Dubosson

University of Applied Sciences Western Switzerland (Fribourg)

Emmanuel Fragnière

University of Applied Sciences Western Switzerland (Wallis),

and University of Bath

Marilyne Pasquier

University of Applied Sciences Western Switzerland (Fribourg)

Cyrille Reynard

University of Applied Sciences Western Switzerland (Wallis)

Introduction

With a share of 27 %, Switzerland is the global market leader in wealth management in terms of volume of business in cross-border private banking (SwissBanking, 2011). The Swiss banks specializing in wealth management are referred to as private banks. The Swiss wealth 18management sector has suffered from two major shocks in the past five years: the financial crisis and the end of Swiss banking secrecy. This pivotal period is thus very interesting to analyze, especially regarding the impacts of these changes on banking service operations. These events were accompanied by a sudden surcharge of enforced international regulations. As wealth management corresponds to a cross-border business, international regulations play a significant role in private banks’ operations (controls, procedures, compliance, security, etc.). That is the case, for instance, of MiFID II (which is a directive on markets in financial instruments promulgated by the EU), the automatic exchange of information imposed by the OECD and all the specific national laws on tax evasion.

As with every service activity, human resources play a key role in the banking industry. In these hectic times, collaborators may have lost their bearings. Bank employees have to meet new constraints while meeting demanding customer expectations. They might not know how to deal with these new contexts. Moreover, complex and varied regulations are difficult to standardize and automatize. Human mistakes are therefore a critical component of the banking process and are often visible to the clients involved in the service experience (Bowen and Schneider, 1985).

Human risks comprise the uncertainties and potential damage that are caused by people (Fragnière and Junod, 2010). Moreover, employees tend to pursue in priority their own personal objectives instead of company’s objectives (Ferrary, 2009). Not only do collaborators create problems, but they also may not act correctly to recover from them. Human risks emerge when the behaviors and failures of the workforce weigh on the competitiveness and sustainability of the company (Fragnière et al., 2010).

The objective of this paper is to investigate the human risk factors leading to higher levels of ill-being that may result in value destruction in the peculiar context of the changing banking environment in Switzerland. The research question that we want to address in this paper is the following: How could human risk lead to value destruction in services?

The authors of this paper conducted an exploratory survey with the help of their EMBA students in risk management (HES-SO) during the period from September 2013 to February 2014. We 19chose to undertake a qualitative study based on semi-structured interviews. We surveyed 35 employees of various Swiss financial institutions, occupying the full range of private banking key positions in Switzerland, such as customer relations manager, portfolio manager, compliance officer and risk manager. Our results showed disruption in human-based operations in private banks resulting in various forms of value destruction. Merging, outsourcing or suppression of activities, recruitment freezes and downsizing are the traditional answers to such disruption. Our research showed the emergence of various demonstrations of precisely human-related risks, such as lower service quality, the loss of decades of experience with the departure of employees and a significant increase in absenteeism and fraud. In brief, we observed that human risks are significant in the conducting of service operations in the context of Swiss private banks. We thus concluded that human risks, when they materialize, lead to ill-being and then value destruction. This finding still needs to be tested in subsequent quantitative research. Likewise, human risk mitigation methodologies have to be tested to prove their impact on the minimization of value destruction in the service sector.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 1, we present a brief literature review essentially concentrating on the notions of human risks, occupational stress, job resources and demands exerting an impact on well-being. In Section 2, we explain the methodology based on semi-directed interviews, which was employed to understand the human risks contributing to ill-being in the Swiss wealth management sector. In Section 3, we present a synthesis of the results based on content analysis of the interviews. In Section 4, we discuss the main results and propose a new theoretical model to mitigate the human risks contributing to the ill-being of the actors involved in a given service experience. In the last section, we conclude and indicate further research directions.

20I. Literature review

In this section, we present the different scientific literatures related to our interdisciplinary research question. We begin with the notion of human risks in service organizations and focus on front-liners’ stress. We then detail the relationship between job demands and resources. We also explain recent developments that relate to the ill-being construct rather that the well-being one. Finally we provide some insights on value destruction and its relationship to performance.

The notion of human risk

in service organizations

Risks can be divided into seven categories of events that could damage the results of a company and hinder the achievement of its objectives: (1) internal fraud; (2) external fraud; (3) employment practices and workplace safety; (4) clients, products and business practices; (5) damage to physical assets; (6) business disruption and system failures; and (7) execution, delivery and process management (Bank for International Settlements, 2001). Among these categories, four are clearly related to employee behaviors (i.e. (1) internal fraud; (2) employment practices and workplace safety; (4) clients, products and business practices; and (7) execution, delivery and process management).

Human risks (or psychosocial risks) correspond to a subset of operational risks. These risks have been defined by the Basel Committee (Bank for International Settlements, 2001) as “the risk of direct and indirect loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events”. Even though operational risks are considered to be mainly a risk of human origin, unfortunately no specific category is assigned to human risks.

Service companies create an environment that is favorable to the emergence of human risks. Mistakes are part of every service, as they are an “unavoidable feature of all human endeavors” (Boshoff, 1997). In the service context, companies have to handle mistakes and mitigate human risks, meaning that they should be able to prevent problems and recover from them. Moreover, rapid changes in today’s marketplace require improved 21monitoring of service organization factors to prevent the potential risks associated with this turbulence (Sauter and Murphy, 2004).

Occupational stress

and front-line employees

Front-line employees in service companies occupy extremely stressful positions (Miller et al., 1988). In the context of private banks, wealth managers have a direct and personal relationship with their clients. Working in a stressful environment increases the risk of suffering from physical illness and/or from psychological distress (Clarke and Cooper, 2004). These negative consequences are especially prevalent when work-induced stress is combined with tensions at home (Boles and Babin, 1996).

The scientific literature defines two distinctive job-related stresses (Fisher and Gitelson, 1983; Jackson and Schuler, 1985; Netemeyer et al., 1990): role conflict and role ambiguity. Role conflict means that workers believe that they are not able to meet the job requirements or feel stretched between customers’ demands and management’s injunctions. Role ambiguity relates to the uncertainty surrounding job tasks (Boles and Babin, 1996).

Stress is not only negative, as it can also result in performance improvement (cf. Behrman; Perreault, 1984). In contrast, burnout (defined as a state of physical and emotional exhaustion) occurs only when stressors overwhelm a person’s coping resources (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984 cited in Singh, 2000). When employees feel that they are unable to bridge a gap with the requirements or expectations placed on them, it may reduce their effectiveness at work and cause health trouble (Toderi et al., 2015). Therefore, studying personal and organizational resources is crucial in the analysis of job-related stress.

Front-line employees are subject to moderate to high levels of burnout, as they may feel torn between the clients’ demands and the organization’s constraints and policies (Cordes and Dougherty, 1993). According to Singh et al. (1994), job burnout is a good indicator of the level of dysfunctional job-related stress. Another major issue regarding burnout is that it often affects the best personnel, namely the employees who are usually skillful and take the initiative (improvise) in the case of service failures (Pines et al., 1981).

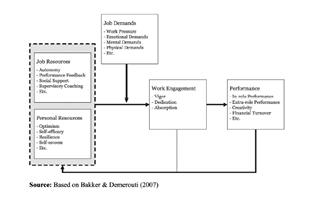

22As a theoretical framework, we chose to study and build our research on the job demands-resources (JD-R) model including its later development concerning work engagement, because it links stressors to performance (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008). This framework was a useful resource laying out the key concepts.

Fig. 1 – Job demands – resources model

(Bakker and Demerouti, 2008, p. 218).

Job resources and job demands

As stated in the framework provided by the JD-R model (2008), job resources comprise factors such as autonomy, performance feedback, social support and supervisory coaching. In their model of burnout, Bakker et al. (2007) included rewards, skill variety, job security, learning opportunities, competence, job control and participation as job resources. Participatory approaches involving employees and employers have been applied to increase job control (Lindström, 1994).

Supervisors’ behaviors have been found to influence a large variety of outcomes, such as job satisfaction, burnout, job neglect and their associated costs (Karimi et al., 2014; Toderi et al., 2015). Autonomy, defined 23as the supervisor understanding and acknowledging the employee’s perspective, providing meaningful information, offering choices and encouraging self-initiative, is also associated with the style of leadership. It promotes self-motivation, satisfaction and performance (Baard et al., 2004), less absenteeism and better physical and psychological well-being (Blais and Brière, 2002 cited in Baard et al., 2004). A negative link has been found between perceptions of destructive leadership style and employee well-being, as employees are more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, emotional exhaustion and reduced enjoyment of their work (O’Donoghue et al., 2016).

To obtain high employee involvement, the management must provide front-line collaborators with autonomy, authority and responsibility (Hart et al., 1989). To deal with the inevitable service failures, banks should concede more autonomy. In particular, in complex situations employees should be able to conduct their own diagnosis (Karmarkar and Pitbladdo, 1995) and rely on their own judgment. However, service industrialization has left employees with little room for maneuver. The banking sector adds another layer of complexity, since service operations must be satisfying for the client and compliant with strict and extensive regulations at the same time. Moreover, due the numerous banking scandals relayed by the press, employees are usually scared to bend the rules to provide the customer with an ad hoc solution. When finding a solution, the service provider has to work in a very emotional environment related to company aspects (e.g. layoffs) as well as to client issues like for instance the fear of being guilty of wrongdoing (Pina e Cunha et al., 2009).

In terms of impact, there is a positive relationship between job resources and work engagement measured as turnover intentions (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004). A resourceful environment fosters employees’ willingness to dedicate their efforts and abilities to performing well and achieving the objectives (Meijman and Mulder, 1998 cited in Bakker, Demerouti, 2008). Job resources are also the most beneficial in maintaining work engagement under conditions of high job demands (Hakanen et al., 2005).

In their various studies, Demerouti, Bakker and their co-authors identified various job demands, such as work pressure, physical workload, poor environmental conditions, demanding clients and time pressure. Some of the job demands are not the most relevant to service settings, as 24they are more related to physical labor. They also categorized demands into emotional, mental and physical demands. In our case, we preferred to refer to more specific job demands that have been identified as influencing employees’ well-being and ill-being.

Furthermore, decreasing role conflict and role ambiguity helps to increase job satisfaction (Barnes and Collier, 2013) and contributes to reducing stress reactions and health disturbances (Cooper and Torrington, 1979 cited in Lindström, 1994). These authors also found the service climate to have an impact on work engagement. The organizational climate, quantitative workload and insecurity (categorized as job resources) are indicators of perceived stress (Lindström, 1994). Organizational roles (which represent the expectations of an individual and of an organization) and the cultural context (defined as the history and values of the organization’s culture) have an important impact on health outcomes (Lindström, 1994). Besides, technological, structural or social turbulence and change pressure can be a threat to work organization and personnel (Lindström, 1994).

Ill-being, the hidden side of work engagement

Well-being within organizations can take different forms. Indeed, well-being involves subjective happiness and satisfaction measured through subjective symptoms (e.g. job satisfaction, perceived health), somatic symptoms (e.g. headaches, palpitations, dizziness, sleep disturbance) and psychological symptoms (e.g. fatigue, nervousness, depression, lack of energy) (Lindström, 1994). Engaged employees experience better health (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004) and positive emotions (Cropanzano and Wright, 2001). Greater overall satisfaction with autonomy, competences and relatedness needs contribute to more positive attitudes and better well-being (Baard et al., 2004).

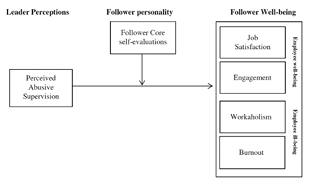

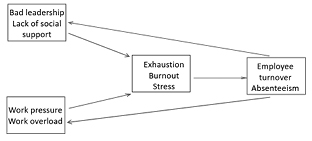

On the other side of the spectrum of well-being is ill-being. For instance, in jobs with high demands and limited job resources, employees develop exhaustion and disengagement (or cynicism), which are the core dimensions of burnout (Bakker et al., 2004; O’Donoghue et al., 2016). The corresponding model is presented in Figure 2. Excessive workload is a predictor of burnout dimensions (García-Izquierdo and Ríos-Rísquez, 2012).

25

Fig. 2 – Research model developed by O’Donoghue et al. (2016)

considering both employee well-being and employee ill-being.

Bakker et al. (2004) defined exhaustion as an extreme form of fatigue due to intense strain caused by prolonged exposure to job stressors. Emotional exhaustion is the opposite of vigor (González-Romá et al., 2006). It diminishes the available energy of an employee and leads to impairment of the efforts put into work (performance) (Singh et al., 1994).

Disengagement refers to negative cynical attitudes and behaviors towards one’s work in general (Bakker et al., 2004). Cynicism is the opposite of dedication (González-Romá et al., 2006). When organizations do not provide rewards or job resources, the consequence is withdrawal from work and reduced commitment as a self-protection mechanism to prevent future frustration from not being rewarded or not reaching goals (Bakker et al., 2004).

Value destruction, the hidden side of performance

Bakker and Demerouti (2007) claimed that work engagement has a direct impact on performance measured in terms of in-role performance (i.e. meeting organizational objectives and effective functioning), extra-role performance (i.e. discretionary behaviors to promote the effective 26functioning of an organization, such as willingness to help colleagues), creativity and financial turnover.

Moreover, when suffering from burnout, employees are not prone to strive for changes in their situation and feel less confident in solving problems. As they feel exhausted, employees are not able to perform well because their energy resources are diminished (Bakker et al., 2004). Burnout also leads to undesired behaviors such as personnel turnover and absenteeism (Bakker et al., 2004).

Besides, a positive relationship has been observed between employee satisfaction and productivity, customer satisfaction and profitability and between work engagement and customer satisfaction and loyalty (Harter et al., 2002). Other studies have found that work engagement is strongly related to creativity (Bakker et al., 2006) and to higher financial returns (Xantho-poulou et al., 2007).

To ensure value creation and avoid the risk of value destruction, human risk management has to be developed. In the professional auditing literature, factors inducing human risks have been identified. For instance, the corporate culture promotes informal policies based on the acceptance and sharing of key values (IIA, 2013). The enterprise culture may also lead employees to misbehave and reinforce illegal activities; for example, companies’ history of corruption tends to make employees repeat inappropriate behaviors (Baucus and Near, 1991). In contrast, a corporate culture that fosters communication and trust between employees and managers, and promotes collaboration between people, reduces the emergence of human risks.

To study the relationships between human risks associated with inappropriate job resources and demands and ill-being, then leading to value destruction, we chose an inductive qualitative approach. The goal was to build new theory by identifying hypothetical relationships to be confirmed in subsequent research. The methodology used in our study is explained in the next section.

27I. Methodology

This study reflects the philosophy of “interpretivism,” which is the most appropriate for the scope of our research. Its main objective is to understand how occupational stress, as a special case of human risk, can become a source of service disruption within Swiss wealth management banks. Thus, a comprehensive and deep understanding of this issue is necessary to conduct data collection and address the research question effectively. Therefore, we believe that this inductive approach (Voss et al., 2002) is the most suitable for our research.

As noted earlier, we followed an ethnographic research strategy. Saunders et al. (2016, p. 189) stated:

Ethnography is relevant for modern organisations. For example, in market research ethnography is a useful technique when companies wish to gain in-depth understanding of their markets and the experience of their consumers.

This approach is well suited to understanding the perceived consequences of the deep structural changes in the Swiss private banking sector following the financial crisis and the end of Swiss banking secrecy. The research process followed different steps (the process was not linear but rather iterative):

–We conducted a thorough literature review to determine the state of the art of research related to human risks in service experiences.

–Based on this literature review, we generated a priori hypotheses.

–We conducted a series of semi-directed interviews.

–The collected data were analyzed using content analysis (with the help of RQDA) based on codes and categories of codes from the literature review.

–We triangulated the results with focus groups as well as unstructured interviews.

28–We developed a new theoretical framework by confirming or refuting our a priori hypotheses and by suggesting new variables to be integrated.

The sampling strategy was a purposive one. We conducted interviews until new knowledge was obtained. Consequently, the choice of respondent profiles was made when the interviews were underway and was thus often combined with a “snowball” approach.

Our survey was conducted among 35 people from several institutions during the period from September 2013 to February 2014. The profiles of the respondents corresponded to various positions occupied in the field of private banking in Switzerland. In particular, our convenience sample was composed of CFOs, financial risk managers, security managers, procurement managers, HR employees, asset managers, management assistants, portfolio managers, back-office employees, compliance officers, operational risk managers, relationship managers. All hierarchical positions found in the private banking sector were represented in the sample, which are employees, middle management and upper management as well as CEO and board members. The sample respondents had spent an average of 15 years in the private banking sector and 8 years in their current position.

We designed a questionnaire with the goal of uncovering “meanings” related to the social phenomenon of ill-being (such as burnout) and the nature of risks contributing to it observed in the Swiss wealth management sector. We conducted semi-structured interviews with bank managers and employees and unstructured interviews with customers and employees. We also used secondary data from various professional publications and reports.

The semi-structured interviews were designed to provide the respondents with enough freedom to address the most important issues to them and to encourage them to share their experiences with the researcher, who would then either redirect the interview to explore additional patterns or ask further questions to deepen the analysis. The structure was as follows. The analyst first met the respondents and asked for a few details of their education, professional path and experience. In this paper we specifically concentrate on the following four questions asked during our semi-directed interviews:

291. How do you feel about your job?

2. In your company have you observed any instance of human risk?

3. What was the evidence that revealed these cases of human risk?

4. In your opinion how are these issues going to evolve in the context of Swiss banks?

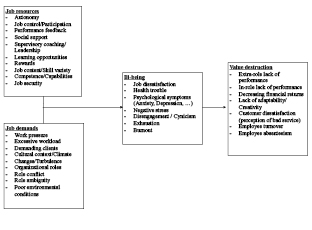

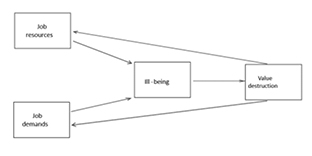

All the interviews were fully and faithfully transcribed. Through our literature review, the key factors and impacts of human risks were identified to constitute a list of codes. More specifically, we used the coding scheme presented in Figure 3. The coding scheme was thus established based on a new model adapted from both Bakker and Demerouti (2008) and O’Donoghue et al. (2016). In the model presented in Figure 3, we eliminated the construct “personal resources” (which belonged to Bakker et al., 2006 cited in Bakker and Demerouti, 2008). The reason for this is that Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) usually concentrates on responses that address risks at a corporate level. ERM thus tends not to directly interfere in the psychology of individuals. Thus our motivation to eliminate the construct “personal resources” is rather practical. We also replaced the notion of well-being with the notion of ill-being as defined by O’Donoghue et al. (2016).

These codes were used for content analysis. All the collected data were uploaded into the RQDA software (part of the open-source R software suite). The whole corpus was then coded. Relevant parts were associated with one or several codes. The coding results were cross-checked by the authors to ensure better validity and reliability. All the code-related content was analyzed.

In the next section, we present the synthesis of the main results obtained from the interview transcripts.

30

Fig. 3 – Revised model (based on Bakker; Demerouti,

2007 and O’Donoghue et al. 2016) used for coding purposes.

I. Results

The results are presented in four sections. The outline follows the logic of the model presented in Figure 3. Consequently, we start with job resources and job demands, than ill-being and finally with value destruction.

Job resources

All the dimensions of the job resources’ category were mentioned throughout the discussions with the interviewees. The most prevalent issue by far was the role of the upper management. The respondents stressed the role of their managers by stating that they are the ones to 31instill values and directions and to create a good work climate. When things go wrong or when uncertainty increases, they should be the best defense and support. However, most of respondents complained about the fact that the managers do not even listen to them (e.g. “I don’t agree to work for a slaver” – interview 15 – senior compliance officer). They felt that managers’ behaviors were disrespectful (e.g. “Shut up was part of everyday vocabulary” – interview 3 – HR manager) and sometimes obviously damaging when using mobbing attitudes. Some of them abdicated their responsibilities and blamed their subordinates in the case of errors or poor performance.

Social support is crucial to survive such poor environmental conditions. These respondents demanded good relationships and continual communication among colleagues. However, employees no longer had time to talk and exchange opinions. There was no more collaboration and solidarity, just more competition.

This phenomenon could be explained partly by the fact that most of the respondents described measures of mass layoffs in their banks. These measures were taken essentially against older employees, who were also the most experienced. The employees no longer felt protected (e.g. “in case of sick leave, the employees are fired as soon as the legal waiting period allows it” – interview 22 – risk manager). As a consequence, they live in fear of losing their jobs.

Employees accept working in a difficult environment if they feel that they receive something in return. However, the Swiss bank employees felt that they were not rewarded fairly and sufficiently considering the high-risk environment, their skills, their knowledge and their performance. In particular, the employees believed that the reward schemes were inappropriate and even toxic. Surprisingly, the bank employees did not complain about the decreasing wages or bonuses. They even thought that the reward systems might be overestimated and might lead to misbehaviors as they promote short-term thinking instead of continuity of jobs and of the company. Above all else, the respondents complained about the non-financial components of rewards. In particular, they suffered from a lack of recognition. Not only was there no sign of gratitude, there was also no perspective and no meaning, just discredit.

32|

Job resources |

# of codings |

# of interviewees |

|

Supervisory coaching / leadership |

49 |

22 |

|

Social support |

18 |

15 |

|

Job security |

21 |

14 |

|

Rewards |

17 |

12 |

|

Autonomy |

21 |

10 |

|

Competence |

13 |

10 |

Tab. 1 – Job resources results – top issues.

Job demands

When talking about their job and related human risks, the respondents explained what was so different in the industry today. They highlighted different contextual factors that might account for the emergence of human risks. Some of the job demands’ dimensions were discussed far more than others. In contrast, the “demanding clients” dimension was not mentioned at all, as the respondents seemed to think that customer requests were fully legitimate.

|

Job demands |

# of codings |

# of interviewees |

|

Changes / turbulence |

31 |

20 |

|

Culture / climate |

41 |

19 |

|

Work pressure |

44 |

18 |

|

Excessive workload |

24 |

18 |

|

Poor environmental condition |

15 |

11 |

Tab. 2 – Job demands’ results – top five issues.

One of the most recurring themes was the new legal framework. The respondents not only complained about the emergence of new rules; they also lamented the conflicting content and the process followed to impose new rules. Some of the new laws that were enforced in Switzerland were imposed by OECD countries that did not follow the same rules 33in states such as Delaware (US) or on the island of Guernsey (GB). This enforcement was perceived as unfair and as an unjustified display of power. The employees felt betrayed by the Swiss Government, as they thought that it did not fight back with adequate determination. These new laws have been rapidly translated into new policies and procedures that were perceived as inconsistent and irrelevant (e.g. “I feel oppressed by the legal framework. I have to deal with an unnecessary burden” – interview 5 – relationship manager).

Ongoing rapidly changing management, regulations, mergers and acquisitions are stress factors for the employees who have trouble fitting in that new world. (Interview 35 – director of stock exchange operations)

This profound change in the legal framework has shaken and weakened the whole industry. It has increased the competitive pressures among Swiss banks as well as other financial markets. Banks are seeking further savings and efficiencies (e.g. “We are in permanent and continuing reorganization since many years” – interview 18 – internal auditor). They are trying to standardize their operations, which seems to be incompatible with the very nature of private banking. Some of them have been bought up or merged. Many employees have been fired even though they were knowledgeable, efficient and well performing, which reinforced the feeling of unfairness (“The Swiss banking system is dehumanized” – interview 6 – head of wealth management). The employees felt that they have to work in a high-risk environment with nothing in return (“Employees have become money pump” – interview 30 – head of risk management; “One asks more without giving more. They milk the cash cow” – Interview 17 – legal and compliance officer).

Ill-being

In particular, the employees were suffering from a lack of respect and meaning. Even within a team, people did not collaborate. Daily survival in some places had become an individual struggle. Disengagement and cynicism were described using aggressive and belligerent words. Some employees (even described as “the enemy within” in interview 15 – senior compliance officer) were at war with their colleagues (“Individualism generates a toxic culture” – interview 10 – human risk manager) and 34even more so with the managers and executive boards (e.g. “Dissatisfied employees want their revenge” – interview 1 – relationship manager). There were no more relations of trust and loyalty.

It’s like Foreign Legion. You come with your weapons and equipment. You don’t care about your employer. Employees are like mercenaries. (Interview 9 – chief security officer)

Sadly, most forms of ill-being were strongly represented in our analysis. The only form of ill-being that was almost completely absent was workaholism (one coding). Alcoholism or over-use of drugs was more present as a derivative for supporting the working conditions (four interviewees mentioned it).

Stress was felt to be ever increasing and impossible to handle. “It had become palpable” (interview 29 – asset manager). For instance, a respondent saw a colleague “physically” falling to the ground (interview 5 – relationship manager). These difficult conditions led to a general feeling of physical and emotional exhaustion expressed in different terms such as lassitude, apathy, persistent fatigue or total exhaustion. The interviewees observed different types of symptoms ranging from depression (the most frequent), withdrawing into oneself, sudden mood changes, nervous breakdown, aggressiveness and sorrow to anxiety. “My colleague did not joke anymore, he was at the end of his rope, he had changed” (interview 7 – private wealth advisor).

|

Ill-being |

# of codings |

# of interviewees |

|

Disengagement/cynicism |

39 |

21 |

|

Burnout |

30 |

18 |

|

Exhaustion |

21 |

14 |

|

Stress |

21 |

13 |

|

Psychological symptoms |

19 |

13 |

Tab. 3 – Ill-being – top five issues.

35Value destruction

In our theoretical model, we identified some types of value destruction. In our analysis, we added one more form that was not identified through our literature review. The most frequent form of value destruction in the context of the Swiss banking industry is fraud and data and money theft. Fraud and theft were more common than might be expected. For instance, a medium-sized bank had to deal with one huge case per year besides lesser damage in a number of others (interview 25 – business developer). According to our respondent, the number of fraud cases was increasing with the growth of employee dissatisfaction and disengagement. There was a phenomenon of “fraud by frustration” (interview 18 – internal auditor) or “active harmfulness” (interview 16 – risk manager).

|

Value destruction |

# of codings |

# of interviewees |

|

Fraud/theft |

67 |

27 |

|

In-role performance |

46 |

25 |

|

Employee turnover |

41 |

23 |

|

Employee absenteeism |

27 |

14 |

|

Customer dissatisfaction / bad service |

10 |

6 |

Tab. 4 – Value destruction – top five issues.

Corporate ill-being resulted in problems of turnover and employee absenteeism. When people suddenly left their occupation for another job or in the case of sick leave, they were usually not replaced. This meant that the work to be performed would be distributed among the remaining colleagues, creating an even larger workload and more stress. When employees quit their job, the bank lost experienced people and all their knowledge and capabilities. “Generally, the best employees left first” (interview 22 – risk manager). All the explicit and tacit knowledge was a loss for the banks but also for the country, as some of them preferred to move to other countries “where there are still business opportunities” (interview 6 – head of wealth management). The available competences were also hurt by disengagement, as it resulted 36in more intentional and non-intentional errors and a lower quality of work. Very often employees chose not to comply with internal rules and procedures as doing so took too much valuable time and they had become less attentive.

All these aspects have a strong impact on customers. Throughout their interactions, employees’ frustration spilled over to the customers, who became depressed and unsatisfied (interviews 6 – head of wealth management – and 31 – portfolio manager). The customers felt as if they were being betrayed by the banks and their representatives, who were not sufficiently available (e.g. “How can you trust a bank when the person of contact is ever changing?” – interview 15 – senior compliance officer). They felt uncomfortable and they left for competitive banks located in foreign countries.

Our bank is like a steamer. We regularly increase the heat. We don’t know when it’s going to explode. But when it will, damages will be huge. (Interview 7 – private wealth advisor)

In the next session, we discuss the synthesis to build theory and provide a new model adapted from Bakker and Demerouti (2007).

I. Discussion

The main finding arising from the results of the field work is that we had not anticipated the importance of the “fraud” variable when considering the “value destruction” construct.

More precisely, the two main identified paths leading to value destruction are as follows:

1. Work pressure and work overload (as “job demands”) combined with bad leadership and a lack of social support (as “job resources”) lead to exhaustion, burnout and stress (as “ill-being”) and ultimately to employee turnover and absenteeism (as “value destruction”).

37

Fig. 4 – Employee turnover and absenteeism,

as an effect and cause of exhaustion, burnout and stress.

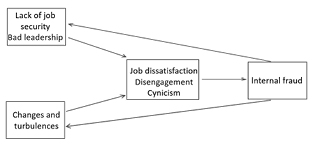

2. Changes and turbulence (as “job demands”) combined with a lack of job security and bad leadership (as “job resources”) lead to disengagement, cynicism and job dissatisfaction (as “ill-being”) and ultimately to fraud (as “value destruction”).

Fig. 5 – Internal fraud, as an effect and cause of job dissatisfaction, disengagement and cynicism.

Consequently, it seems as if both cases correspond to vicious circles. Absenteeism and turn-over increase stress and workload, since the 38remaining employees have to deal with far more. Similarly, fraud and related scandals increase turbulence. Indeed, banking crimes are often unpunished, and this contributes to more cynicism among the employees. The danger of such vicious circles is that specific cases that could have been prevented can end up having dramatic consequences. A few examples in the banking sector are massive layoffs, no more prospects for employees who are more than 50 years old, copycat suicides and so on. This discussion enables us to draw a new model, as presented in Figure 6.

Fig. 6 – New adapted model in which “job resources and demands”

lead to “ill-being” and then to “value destruction”

with a loop towards “job resources and demands”.

According to Wacker (1998), theory building is grounded on the four following components: a) definitions of terms and variables; b) a domain (i.e. the exact setting in which the theory can be applied); c) a set of relationships; and d) specific predictions. We then employ this outline to build some new theory.

Human resources play a key role in the banking industry. We assumed that in hectic times human-related risks, defined as potential damage caused by people, will increase and hinder value creation or even destroy value. Employees experiencing stressful situations may create problems and/or not act correctly as a result of disengagement. According to the JD-R model and further research, engagement and other well-being dimensions are the results of job-related demands and resources.

39We studied the impact of changes in wealth management in Geneva (a city that is certainly the most known for this specific service sector) over the last years. We observed a conjunction of sudden and huge stress on both wealth managers and clients (loss of bank secrecy, profit margin reduction due to fierce competition and transparency regulation, foreign fiscal policy, etc.).

Improved well-being leads to better value (co-)creation. We studied the impact of job-related demands and resources on the opposite of well-being (i.e. ill-being) and on potential value destruction. Well-being in the service sector is typically affected by human risks taking place during the interaction between the service provider and the client. A stressed client and/or a stressed service provider can prevent value creation. Contagion is most likely to occur when employees are stressed, frustrated and dissatisfied. Stressful service interaction situations can be detected in advance and be properly mitigated if the stressors are correctly identified. Our model also adds this notion of a loop between the “value destruction” construct and the “job demand and resources” construct, leading to a model describing a vicious circle.

To prevent human risk from happening, actions can solely be taken at the micro-management level. This was raised by most of the respondents in our data sample. It means that there is a need for more proximity, direct communication as well as trust in human interactions. To avoid any contagion, one must handle these human risks upstream. As it is advocated by risk management standards, it is better to address the causes at the origin of the risk rather than its consequences (“prevention is better than cure”). The JD-R model, as we have adapted it, could thus constitute a practical approach to addressing the risk more upstream directly at the levels of job demands and resources to prevent these vicious circles from occurring. Our results also highlighted the crucial role of managers in preventing (or reinforcing) human-related risks. For the predictions arising from the application of this model to be confirmed in reality, we need to test this model in subsequent research to make it really usable.

Although the developed model requires to be tested through a quantitative study, we already foresee relevant theoretical implications for the field of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM). Based on this model, we can posit that value destruction reinforces stressors as part of a vicious 40circle. This is represented by the “human risk – value destruction loop” which includes the possibility of a contagion effect. Moreover, the originality of our model is to provide responses that address the causes at the origin of the risks rather than its consequences. Additionally, a direct managerial insight that arises from our fieldwork is that there is an urgent need for more proximity, direct communication and trust between employees and management in the private banking sector.

The two main ERM standards are ISO 31000 and COSO ERM. Both standards put the emphasis on corporate risks. However these standards do not integrate any human risk categories so far. For instance, ISO 31000 just encourages its users to take into account the human factor. Consequently, no risk detection and response dispositions are available today to address human risks in the organization. This research thus aims at contributing to bridge this gap. We can mention the recent work of Palermo et al. (2016) who claims that ERM is deployed in most medium and large scale enterprises worldwide and that there is need for more research to improve the overall efficacy of risk responses in more and more complex organizations.

Conclusion

Switzerland is the global market leader in wealth management. The Swiss wealth management sector has suffered from two major shocks in the past years: the financial crisis and the end of Swiss banking secrecy. Following these shocks, new stringent international banking regulations have been enforced in a very short period of time. Their implementation has resulted in huge problems of work stress and burnout for the employees. Swiss bank employees used to live in a privileged environment providing high financial rewards, social status and job security. As the context changed, they feel that they have lost everything and have to cope with a hostile and even toxic work environment.

These changes associated with other dimensions of job resources and demands had a strong impact on employees’ well-being, or rather on its opposite, their ill-being. As the leadership was not able to deal 41properly with all these changes, but just reacted by laying off numbers of employees, especially the most experienced ones, the service climate changed and put even more pressure on unsecure employees. The symptoms of ill-being were varied, ranging from cynicism, burnout, exhaustion and stress to depression, among others. Ill employees reduced their engagement and displayed undesired behaviors. Above all, they could observe numerous cases of fraud and theft. Acts of value destruction would then reinforce stressors as part of a vicious circle.

Further research is needed to test and validate these relationships and their strength using quantitative surveys. We have already started to collect related quantitative data to analyze them and test this new model with statistical inferences. This model (human risks – value destruction loop) should also be tested in different contexts, as wealth management might display a specific culture linked to everyday contact with money and opportunities to steal from the assets to be managed.

From the perspective of risk management, the existing methodologies should be applied and adapted to check their effectiveness and to measure their impact. The results might call for the development of new methods that are better suited to human-related risks. In particular, more attention has to be devoted to human-related risks within service settings, as service production heavily involves humans of two kinds: providers and customers. Better service will rely on the well-being of all the actors involved in the delivery of the service experience. Further research might also specifically study the impact of these relationships on the value co-creation process.

42References

Baard P. P., Deci E. L., Ryan R. M. (2004), “Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), p. 2045-2068.

Bakker A. B., Demerouti E. (2007), “The job demands-resources model: State of the art”, Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), p. 309-328.

Bakker A. B., Demerouti, E. (2008), “Towards a model of work engagement”, Career Development International, 13(3), p. 209-223.

Bakker A. B., Demerouti E., Verbeke, W. (2004), “Using the job demands–resources model to predict burnout and performance”, Human Resource Management, 43(1), p. 83-104.

Bakker A. B., Gierveld J. H., Van Rijswijk K. (2006), Succesfactoren bij vrouwelijke-schoolleiders in het primair onderwijs: Een onderzoek naar burnout, bevlogenheid en prestaties (Success Factors among Female School Principals in Primary Teaching: A Study on Burnout, Work Engagement, and Performance). Diemen: Right Management Consultants.

Bank for International Settlements (2001), QIS 2 – Operational Risk Loss Data. Retrieved on December 2, 2014 from http://www.bis.org/bcbs/qisoprisknote.pdf

Barnes D. C., Collier J. E. (2013), “Investigating work engagement in the service environment”, Journal of Services Marketing, 27(6), p. 485-499.

Baucus M. S., Near, J. P. (1991), “Can illegal corporate behavior be predicted? An event history analysis”, Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), p. 9-36.

Behrman D. N., Perreault Jr W. D. (1984), “A role stress model of the performance and satisfaction of industrial salespersons”, Journal of Marketing, 48(4), p. 9-21.

Blais M. R., Brière N. M. (2002), “On the Mediational Role of Feelings of Self-Determination in the Workplace: Further Evidence and Generalization” (no 2002s-39). CIRANO.

Boles J. S., Babin B. J. (1996), “On the front lines: Stress, conflict, and the customer service provider”, Journal of Business Research, 37(1), p. 41-50.

Boshoff C. (1997), “An experimental study of service recovery options”, International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(2), p. 110-130.

Bowen D. E., Schneider, B. (1985), “Boundary-spanning-role employees and the service encounter: Some guidelines for management and research”, Service Encounter, p. 127-147.

Clarke S., Cooper C. L. (2004), Managing the Risk of Workplace Stress: Health and Safety Hazards, London, Routledge.

43Cooper C. L., Torrington D. (1979), Identifying and Coping with Stress in Organizations: The Personnel Perspective. Stress at Work, New York, John Wiley & Sons.

Cordes C. L., Dougherty T. W. (1993), “A review and an integration of reseach on job burn-out”, Academy of Management Review, 18(4), p. 621-656.

Cropanzano R., Wright T. A. (2001), “When a ‘happy’ worker is really a ‘productive’ worker: A review and further refinement of the happy-productive worker thesis”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 53(3), p. 182-199.

Demerouti E., Bakker A. B., Nachreiner F., Schaufeli W. B. (2001), “The job demands-resources model of burnout”, Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), p. 499-512.

Ferrary M. (2009), “Les ressources humaines à risque dans le secteur bancaire: une application de la gestion des risques opérationnels”, Gestion 2000, 29(2), p. 85-102.

Fisher C. D., Gitelson R. (1983), “A meta-analysis of the correlates of role conflict and ambiguity”, Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(2), p. 320-333.

Fragnière E., Gondzio J., Yang X. (2010), “Operations risk management by optimally planning the qualified workforce capacity”, European Journal of Operational Research, 202(2), p. 518-527.

Fragnière E., Junod N. (2010), “The emergent evolution of human risks in service cmpanies due to control industrialization: An empirical research”, Journal of Financial Transformation, vol. 30, p. 169-177.

García-Izquierdo M., Ríos-Rísquez M. I. (2012), “The relationship between psychosocial job stress and burnout in emergency departments: An exploratory study”, Nursing Outlook, 60(5), p. 322-329.

González-Romá V., Schaufeli W. B., Bakker A. B., Lloret S. (2006), “Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles?”, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(1), p. 165-174.

Hakanen J. J., Bakker A. B., Demerouti E. (2005), “How dentists cope with their job demands and stay engaged: The moderating role of job resources”, European Journal of Oral Sciences, 113(6), p. 479-487.

Hart C. W., Heskett J. L., Sasser Jr W. E. (1989), “The profitable art of service recovery”, Harvard Business Review, 68(4), p. 148-156.

Harter J. K., Schmidt F. L., Hayes T. L. (2002), “Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis”, Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), p. 268-279.

IIA (Institute of Internal Auditors) (2013), CIA syllabus 2013. Available at https://na.theiia.org/certification/Public%20Documents/CIA%20syllabus.pdf

44Jackson S. E.; Schuler R. S. (1985), “A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36(1), p. 16-78.

Karimi L., Gilbreath B., Kim T. Y., Grawitch M. J. (2014), “Come rain or come shine: Supervisor behavior and employee job neglect”, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 35(3), p. 210-225.

Karmarkar U. S., Pitbladdo R. (1995), “Service markets and competition”, Journal of Operations Management, 12(3), p. 397-411.

Lazarus R. S., Folkman S. (1984), Stress, appraisal, and coping, New York, Springer publishing company.

Lindström K. (1994), “Psychosocial criteria for good work organization”, Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 20(Special Issue), p. 123-133.

Meijman T. F., Mulder G. (1998), “Psychological Aspects of Workload”, in P. J. D. Drenth P. J. D, Thierry H., & de Wolff C. J. (Eds.), New Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology. Volume 2. London, Sage, p. 5-34.

Miller A., Springen K., Gordon J., Murr A., Cohen B., Drew L. (1988), “Stress on the Job”, Newsweek, (April 25), p. 40-45

Netemeyer, R. G., Johnston, M. W., Burton S. (1990), “Analysis of role conflict and role ambiguity in a structural equations framework”, Journal of Applied Psychology, 75 (April), p. 148-157

O’Donoghue A., Conway E., Bosak J. (2016), “Abusive supervision, employee well-being and ill-being: The moderating role of core self-evaluations”, in Ashkanasy N., Härtel C. E. J., Zerbe W. J. (Eds.), Emotions and Organizational Governance (Research on Emotion in Organizations, Volume 12). Bingley, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, p. 3-34.

Palermo T., Power, M., Ashby S. (2016), “Navigating institutional complexity: The production of risk culture in the financial sector” Journal of Management Studies, 54(2), p. 154-181.

Pina e Cunha M., Rego A., Kamoche K. (2009), “Improvisation in service recovery”, Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 19(6), p. 657-669.

Pines A. M., Aronson E., Kafry D. (1981), Burnout: From Tedium to Personal Growth, New York, Free Press.

Saunders M., Lewis P., Thornhill A. (2016), Research Methods for Business Students. 7th edition. Harlow, Pearson.

Sauter S. L., Murphy L. R. (2004), “Work organization interventions: State of knowledge and future directions”, Sozial-und Präventivmedizin, 49(2), p. 79-86.

45Schaufeli W. B., Bakker A. B. (2004), “Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), p. 293-315.

Singh J., Goolsby J. R., Rhoads G. K. (1994), “Behavioral and psychological consequences of boundary spanning burnout for customer service representatives”, Journal of Marketing Research, 31(4), p. 558-569.

SwissBanking (2011), Wealth Management in Switzerland: Status, Reports and Trends. Available at www.swissbanking.org

Toderi S., Gaggia A., Balducci C., Sarchielli G. (2015), “Reducing psychosocial risks through supervisors’ development: A contribution for a brief version of the Stress Management Competency Indicator Tool”, Science of the Total Environment, 518, p. 345-351.

Voss C., Tsikriktsis N., Frohlich M. (2002), “Case research in operations management”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22(2), p. 195-219.

Wacker J. G. (1998), “A definition of theory: Research guidelines for different theory-building research methods in operations management”, Journal of Operations Management, 16(4), July, p. 361-385.

Xanthopoulou D., Bakker A. B., Demerouti E., Schaufeli W. B. (2007), “The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model”, International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), p. 121-141.