Municipal services within the framework of Local Agenda 21 A comparison between Norway and Spain

- Publication type: Journal article

- Journal: European Review of Service Economics and Management Revue européenne d’économie et management des services

2016 – 2, n° 2. varia - Authors: Navarro Espigares (José Luis), Maraver Tarifa (Guillermo), Martín Segura (José Aureliano), Buck (Marcus), Saethre (Mari Ann), Midtbø (Tor), Pérez López (César)

- Abstract: The objective of this paper is to compare Norwegian and Spanish municipalities regarding their commitment to environmental expenses and citizen participation within Local Agenda 21. Models estimated using the difference in differences methodology present positive and statistically significant impact of LA21 on municipal expenses in environmental programs. These positive results appear concentrated in Norwegian small towns and in the medium-sized and large Spanish municipalities.

- Pages: 115 to 147

- Journal: European Review of Service Economics and Management

- CLIL theme: 3306 -- SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES -- Économie de la mondialisation et du développement

- EAN: 9782406069300

- ISBN: 978-2-406-06930-0

- ISSN: 2555-0284

- DOI: 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-06930-0.p.0115

- Publisher: Classiques Garnier

- Online publication: 05-27-2017

- Periodicity: Biannual

- Language: English

- Keyword: Local Agenda 21, municipalities, environmental expenditures, Norway, Spain

Municipal services within

the framework of Local Agenda 21

A comparison between Norway and Spain

José Luis Navarro Espigares, Guillermo Maraver Tarifa, José Aureliano Martín Segura, University of Granada

Marcus Buck, Mari Ann Saethre, UiT The Arctic University of Norway

Tor Midtbø, University of Bergen

César Pérez López, Complutense University of Madrid

Introduction

The Agenda 21 document is different from the other three documents adopted in 1992 at the Earth Summit, because it is a plan of action. The implementation locally of the LA21 makes it possible to design intervention strategies for sustainability based on cooperation between governments and social partners. It is a strategic plan with the intention that the cities and municipalities assume their share of responsibility for the mobilisation of the citizens. Thus, local populations 116would participate in the effective management of the territory and the promotion of fair and long-lasting scenarios from the environmental, social, and economic points of view.

Regarding the management of collective proposals and problems related to legitimacy of governmental interventions, the sustainable development model boosts the value of participatory democracy, moving a large part of the role to citizens at the local level (Brunet Estarellas, Almeida García, and Coll López, 2005). The Local Agenda 21 (LA21) meets these objectives and, therefore, is currently one of the main instruments of management and intervention in favour of sustainable development (“European Sustainable Cities Platform–AALBORG +10 2004”, s. f.). In Spain, the endorsement of LA21 by local governments has been particularly strong. In 2010 the full list of signatories to the Aalborg Charter included 2,838 participants, 1,237 of them being Spanish municipalities.

The strong support of the regional governments is the determining factor in explaining the intense movement of adhesion to the LA21 by the Spanish municipalities. The Autonomous Communities have developed programs that promote the implementation of LA21, the majority of them starting with the realisation of an environmental diagnosis and the provision of funding lines for municipalities that initiate these processes. Some regional governments have gone further, developing their own sustainability strategies and working with groups of municipalities, also advising them and providing them with tools (staff training, publication of methodological guides, design of indicators, etc.) (Aguado et al.).

Nevertheless, there have been several studies that have questioned the authenticity of political commitment towards meeting the objectives of sustainable development by local governments that have adhered to the Local Agenda 21. Thus, the idea is to link environmental expenditure with the political commitment of local governments to achieve the goals set by the LA21.

In addition, in Spain most of the projects considered examples of good practice are linked to relevant initial investments (Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias-FEMP & Observatorio de la Sostenibilidad en España-OSE, 2013). This circumstance makes it reasonable to link the political commitment to the variable “environmental expenditure”.

117In Norway, in many areas of environmental policy, in particular regarding pollution and waste, some progress can be noted. To mention but one example, it is good news that the part of household waste which is recycled has increased from close to zero to some 40 percent over the last 15 years. The bad news, however, is that within the same period of time household waste per person has increased by more than 50 per cent, and the trend is projected to increase over the next decade.

Furthermore, with respect to sustainable development, increasing conflicts of interests over the use of land and natural resources in this country must be faced, and the public system to safeguard long-term public interests in land-use planning, including environmental protection, is definitely weaker today than it was 10 years ago, mainly due to the impact of private interests and market forces.

Norway realised how complex it is in practice to achieve sustainable development. Although its scientific community aims for it to be a leading nation in the study of sustainable development issues and to improve the interface between research and decision making, yet rationality in policy-making and implementation seems to be an elusive goal. Politicians tend to simply avoid knowledge that doesn’t correspond to current political priorities.

The environmental policy integration refers to the integration of environmental concerns into other policy areas. Norway made an early start with policies for environmental policy integration. However, the implementation of Environmental Policy Integration initiatives has been slow and piecemeal. In the opinion of some authors, due to the weakness of the horizontal dimension of the integration policy, the ambition of Agenda 21: “to harmonise the various sectoral economic, social and environmental policies and plans” has been broadly neglected (Hovden and Torjussen, 2002).

Regarding the implementation of Local Agenda 21, aspects of the Norwegian system of governance lead to very divergent results in different types of municipalities. By the year 2000, 117 out of Norway’s 435 municipalities had removed the position of environmental officer entirely, while 134 municipalities had either reduced its scope of responsibility, or merged it with another position (Bjørnæs and Norland, 2002).

The objective of this paper is to compare the behaviour of Norwegian and Spanish municipalities and find differences and similarities with 118respect to some goals included in the Local Agenda 21. Specifically, we will study the commitment of those municipalities that adhered to LA21 to environmental expenses and citizen participation.

Several specific objectives help to disclose in detail those inter-country differences and similarities, regarding the behaviour of municipalities in the control group (non LA21 municipalities) and the experimental group (LA21 municipalities):

–Expenditure in general expenses related to environment

–General environmental expenses plus expenditure in water and waste programs

–Expenditure in environmental programs related to water

–Expenditure in environmental programs related to waste and renovation

–Citizen participation in local elections (voter turnout)

The research questions addressed in this paper are the following:

–Do the municipalities that adhered to the LA21 devote more budgetary resources to environmental expenditures?

–Do the municipalities that adhered to the LA21 present a greater voter turnout?

–Is the population size of municipalities a differential factor for the behaviour of local governments?

We did not find answers to these questions in the empirical literature on the assessment of LA21 experiences. Thus, in order to respond to these questions, we will solve five econometric models by means of the technique known as Difference-in-Differences (DiD) (time-constant differences and time-trends differences between treatment and control groups) that refer to each country and then we will compare the results obtained. In accordance with the difference in differences methodology, we will compare the experimental group (municipalities that adhered to LA21) in each country with the control group (municipalities that did not adhere to LA21), in two different years 2002 and 2012.

The differential contributions of this work can be summarised in terms of the following aspects:

119–The dependent variable is the environmental expenditure, understood from the perspective of the functional classification of municipal budgets

–The methodology implemented for measuring the impact of public policies is DiD

–Municipal entities are utilised as the unit of analysis

The following section describes the development of the LA21 in Europe. In this section we will also offer a brief presentation of the main issues found in the literature about LA21 in Spain and Norway. The methodology section specifies the hypotheses tested, the temporal and geographical scopes of the work, the data sources, and the treatment of these data for the selection of the final sample. Then, in the results section we will present our findings, differentiating them in accordance with the population size of municipalities. The analyses, independently carried out for each country by means of the econometric models (DiD), will be exhibited in several comparative tables. We will complete the work with a conclusions section, where the results referring to the hypotheses posed in the methodology section are discussed. Work constraints and major implications for local politics are also included in that section. Finally, we also discuss further research lines in the future, to complement this study.

I. Local governments

and environmental management

(Local Agenda 21 and Aalborg Charter)

The Rio Summit (1992)

The commitment, adopted at the Rio Summit in 1992, to promote sustainable development was reflected in four documents:

–The Declaration of Principles

–WHO Framework, Convention on Climate Change

–The Convention on Biodiversity

–Agenda 21

120Agenda 21 consists of 4 sections developed into 40 chapters, in which the following issues are addressed: social and economic dimensions, conservation and management of resources for development, strengthening the role of major groups and means of implementation. The basis for action, objectives, activities and means of implementation for approval of the Local Agenda 21 are set out in chapter 28 of the third section (Initiatives of local authorities in support of Agenda 21).

When it was adopted in 1992 at the Earth Summit, Agenda 21 was meant to be “a programme of action for sustainable development worldwide”. Furthermore, as stated in its introduction, it had the ambition of being “a comprehensive blueprint for action to be taken globally, from now into the twenty-first century”. The ambition was high, and so were the stated goals of the Agenda: to improve the living standards of those in need; to better manage and protect the ecosystem; and to bring about a more prosperous future for all.

Since the Rio Conference, a timetable for implementation of Agenda 21 has been designed. That schedule included an advisory process at the beginning to encourage cooperation between local authorities at an international level. The first target stated that in 1996 local authorities of each country would have carried out the initial consultative process with their populations to agree on Agenda 21 at the local level.

The Aalborg Charter (1994)

The International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI), which prompted the First European Conference on Sustainable Cities & Towns, held in the Danish city of Aalborg in 1994 at the request of the European Commission, played a decisive role in the process of intermediation between international organisations and local authorities. At this Conference, the Aalborg Charter (Charter of European Cities and Municipalities for Sustainability) was adopted. The signature and adhesion to the Charter by local administrations is identified as the first step in the process of implementing LA21.

The ‘Aalborg Charter’, approved in 1994, is an urban environment sustainability initiative approved by the participants at the first European Conference on Sustainable Cities & Towns in Aalborg, Denmark (Brunet Estarellas et al., 2005). It was inspired by the Rio Earth Summit’s Local 121Agenda 21 plan, and was developed to contribute to the European Union’s Environmental Action Programme, ‘Towards Sustainability’.

The Charter is based on the consensus of individuals, municipalities, NGOs, national and international organisations, and scientific bodies. There are three related parts to the Charter:

–Part 1 is a consensus declaration of European sustainable cities and towns towards sustainability.

–Part 2 relates to the creation of the European Sustainable Cities & Towns Campaign.

–Part 3 is a declaration of intent that local governments will seek to engage in Local Agenda 21 processes.

The conference in Aalborg (1994) was followed by others, such as those held in Lisbon (1996), Turku (1998), Sofia (1998), Seville (1999) and The Hague (1999), which addressed the need to strengthen participatory structures in the development of the LA21 at the regional level.

The XXI century started with additional conferences–Hannover (Germany) 2000, Aalborg (Denmark) 2004, Seville (Spain) 2007, Dunkerque (France) 2010, Geneva (Switzerland) 2013, Bilbao (Spain) 2016. Gathering over 1000 participants from local governments and a variety of other actors across Europe, the European Conference on Sustainable Cities and Towns remains the largest European event for local sustainability. All conferences have been co-organised by ICLEI, together with the respective host cities and a Conference Preparatory Committee.

At the Third European Conference on Sustainable Cities held in the German city of Hannover in 2000, the need to standardise and regulate the different initiatives and give administrative support was raised. In this sense, the presentation of an initiative of systematic monitoring by defining specific standards or sustainability indicators was one of the major contributions of this conference. The final agreement stressed the need to establish and develop regional networks that enable greater cooperation, exchange of experiences and dissemination of good practices, while ensuring greater economic and technical coverage of the various governments. Regarding this last point, the European institutions are encouraged to approve subsidies and grants under the Structural Funds scheme, subject to the existence of a sustainable development plan.

122In the late nineties, 650 regional and local authorities from 32 European countries had made a commitment to local sustainability by joining the Aalborg Charter. In 2010 the number of local authorities that had signed the Aalborg Charter amounted to 2,838.

The Aalborg Commitments (2004)

Ten years after the release of the Aalborg Charter, the participants of the 4th European Conference on Sustainable Cities and Towns in Aalborg, Denmark 2004 (Aalborg+10) adopted the Aalborg Commitments–a list of 50 qualitative objectives organised into 10 themes: Governance, Local management towards sustainability, Natural common goods, Responsible consumption and lifestyle choices, Planning and design, Better mobility, Less traffic, Local action for health, Vibrant and sustainable local economy, Social equity and justice, and Local to global.

Local stories about the achievements in these 10 themes can be accessed at the sustainable cities webpage at http://www.sustainablecities.eu/local-stories/actionforhealth/.

The move from Charter to Commitments signified a new, more structured and ambitious approach. To be signed by the political representative, the document requires the signatory to comply with time-bound milestones. Each local government is asked to produce a baseline review within a year of signature, conduct a participatory target-setting process, and arrive at a set of individual local targets addressing all 10 themes within two years, as well as to commit to regular monitoring reviews.

Agenda 21 recognises nine major groups of civil society and stipulates the need for new forms of participation at all levels, to enable a broad-based engagement of all economic and social sectors for bringing about sustainable development. The Major Groups are Business and Industry, Children and Youth, Farmers, Indigenous Peoples, Local Authorities, NGOs, Scientific and Technological Community, Women, and Workers and Trade Unions. In this work, we will focus our interest on Local Authorities.

As in 1994 with the organisation in June 2004 of the European Conference on Sustainable Towns (Aalborg + 10), the city of Aalborg again became the capital of the local movement for sustainability. The Conference assessed the existence of a large, active and aggressive local movement in favour of a more sustainable model of development, as 123well as the significant increase in the number of cities and municipalities that held to the Aalborg Charter. However, the success achieved over the past ten years has been devalued, because it was found that adherence to the Charter of Aalborg sometimes did not mean more than just an institutional declaration of good intentions, without anything definite or any action plan having been implemented (Brunet Estarellas et al., 2005). This last idea inspires the basis for comparison between Spanish and Norwegian municipalities in the present work, in which the correspondence between the adherence to LA21 by local governments and the economic and budgetary support to sustainable projects will be verified.

In Spain, the Sustainable Development Strategy was introduced by the Government in June 2000 and included the commitment to promote a new model of integration and the balancing of economic, social development and environmental protection in the long term. However, there was a lot of criticism from certain political parties concerning the general nature of the document, the lack of budgetary measures necessary for momentum as well as a framework of broad and representative social participation, and the absence of goals, commitments, priorities and specific deadlines. Given the discontent with the Spanish Sustainable Development Strategy, some regional governments drafted their own plans or strategies for sustainable development. In short, in Spain ‘LA21 has become the symbol that presumes to include everything that is done at the local level to convert the overall design of sustainability into operational reality’ (Font and Subirats, 2000).

In Norway, with the Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland as chair of the World Commission on Environment and Development, the country became an early mover in politics for sustainable development. The pursuit of sustainable development goals has been expressed in several national policy documents, though it was not until 2002 that Norway adopted an explicit ‘National Strategy for Sustainable Development’. This was followed up by a ‘National Action Plan for Sustainable Development’ in 2003. Neither of these initiatives was actively implemented. The article presents and assesses strategic SD initiatives from 1989 to the present day. The Norwegian sustainable development profile is ‘long on promise’ and ‘short on delivery’, and one major reason for this is the influence of a 124booming petroleum economy on distributional politics. An exceptional growth in public revenues due to oil and gas fosters intense political competition over the dispensation of economic and welfare benefits– both between political parties and within governing coalitions– and undermines the ‘political will’ to pursue the sustainable development agenda (Lafferty et al. 2007).

Critical views

Most works studying the development of LA21 in different geographical environments focus on analysing the implementation strategies of the Agenda at the local level. Sustainability as defined by the Brundtland Commission is an ambitious policy target. Environmental, economic, social, and institutional criteria are all considered to be of equal importance. Because of this complexity, the first step of a Local Agenda 21 process should be to develop a vision of a sustainable society based on indicators to measure the progress (Valentin and Spangenberg, 2000). This panel of indicators has not been published in Spain, so we cannot focus our comparative analysis on real outcomes achieved.

Regarding the support given by LA21 to involvement of citizens and stakeholders, specialised literature offers contradictory views. For instance, Adolfsson (2002) studied four small–to medium-sized municipalities in the southeast of Sweden. The study shows that the LA21 processes have instigated many new ideas, brought fields together and introduced new subjects into the municipal realm. It also confirms that there are signs of extended dialogue and public influence, especially where citizens are directly involved. LA21 does not seem to have much influence on the type of natural resources protected, but on how the resources are dealt with. New stakeholders within and outside the municipal organisation have been identified through the LA21 processes, and more comprehensive ways of solving problems as well as a positive climate for testing new ideas have been created. In these respects, LA21 has been and will be a significant support for the development of appropriate natural resource management at the local level. Thus, Aldolfsson’s study confirms that LA21 promotes a broad participation of the different agents in environmental management. In recent years we have found other works in a similar vein (Foh Lee, 2001; Eckerberg and Forsberg, 1998; Agger, 2010).

125A realistic counterpoint to the official monitoring and assessment of LA21 has been offered by Lafferty and Eckerberg (2013). These authors highlighted the problems of assessment and clearly set out the policy stages necessary for more effective attainment of Local Agenda 21 objectives.

Another widely explored perspective for the LA21 analysis is focused on the measurement of sustainable development outcomes anticipated by the Agenda (Poveda and Lipsett, 2011; Thomas, 2010). Thomas pointed out that the literature-based review demonstrates the richness of this engagement and that, while there is enough information about the range of engagement, there is little evidence to indicate the effectiveness of these policies. The assessment process implies the existence of tools, instruments, processes, and methodologies to measure performance in a consistent manner with respect to pre-established standards, guidelines, factors, or other criteria. Sustainability assessment practitioners have developed an increasing variety of tools. Thomas’s paper discusses a range of fundamental approaches, as well as specific and integrated strategies for sustainability assessment, as the foundation of a new rating system being developed for large industrial projects. In this line of research we also found several recent papers (Devuyst, 1999; Haapio and Viitaniemi, 2008; Lawrence, 1997; Nijkamp and Pepping, 1998; Papadopoulos and Giama, 2009; Cole and Valdebenito, 2013).

Regarding the disparities observed in LA21 outcomes, the characteristics of the social organisation used by European municipalities to develop Local Agenda 21, as well as their political structures, have been analysed in 97 European towns subscribing to the Aalborg Charter (Prado and García, 2009). The results pointed to the importance of organisational structure, but only a limited effect of the political structure is observed.

Hess and Winner (2007) summarised some case studies and recommended local government action in favour of environmental sustainability. In their opinion there are many opportunities for financially constrained cities for development of ‘just sustainability’ projects with minimal financial commitments. They can do so by rechannelling the purchasing decisions of public agencies, building partnerships with community organisations and developing the small business sector.

126LA21 Implementation

Europe

The study “Sustainable Development in the 21st century” (2012) offers a detailed (“realistic”) review of progress in implementation of Agenda 21 from an international perspective. It reveals how various chapters of Agenda 21 have progressed at different speeds. Success in Agenda 21 has been highly variable. Despite being a comprehensive plan to deliver sustainable development, implementation has not always been systemic. For example, Agenda 21 has stimulated a much stronger notion of participation in decision making. This important role of non-governmental actors is being affirmed at all levels of government, international law and international governance. Although Agenda 21 has acquired wide acceptance among nation states, its implementation remains far from universal or effective. Progress has been uneven, and despite some elements of good practice, most Agenda 21 outcomes have still not been achieved.

Nevertheless, with regard to our main interest in this work, Local Agenda 21 has been one of the most extensive follow-up programmes to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) and is widely cited as an unprecedented success in linking global goals to local action. Many local authorities around the world have adopted some kind of policy or undertaken activities for sustainable development, either as a main priority or as a crosscutting issue. The progress so far does not mean that the work is over, but rather that there is potential to build further on the success. Multi-level governance is needed, as well as increased integration between local authorities and multi-stakeholders in their communities (Stakeholder Forum for a Sustainable Future, 2012).

The Local Authorities’ Self-Assessment of Local Agenda 21 (LASALA) project, which conducted a Europe-wide research programme into the European LA 21 initiative, demonstrates the significant levels of commitment to the LA 21 process among European local governments and some notable achievements in sustainable development policies within a very short space of time. Although there is still a long way to go, the LASALA research indicates that LA 21 is an effective policy vehicle for 127encouraging and supporting sustainable development initiatives at the local level in Europe (Evans and Theobald, 2003). In a European perspective, the introduction of LA21 to cities can be considered a success story, but these activities are not distributed equally in Europe (Joas, M. and Grönholm, B, 2004).

Spain

Regarding the assessment of the degree of implementation of LA21 in Spain, several recently published studies provide a complete picture of the situation (Font and Subirats, 2000; Hernández Aja, 2003; Echebarria et al. 2004; Moralejo et al. 2007; Hidalgo, 2008; Martínez and Rosende, 2011; Observatorio de la Sostenibilidad, 2014), Jiménez Herrero, 2008).

As regards the adoption of Local Agenda 21, Barrutia and Echebarria (2011) proposed a measurement model to test the case of a specific region, the Basque Country. Research results showed that the adoption of LA21 by local governments is explained by internal characteristics of local governments and factors associated with the local government’s environment and is fostered fundamentally by higher levels of government that can create connected or networking processes. The most relevant external factors are associated with the concept of co-creation. They proposed that, to achieve generalised diffusion of LA21, co-creation in networks, instead of networks in general, should be emphasised.

Concerning the environmental expenditure, we would like to remark on the work by Aguado and Echebarria (2004) in which, by simple correspondence analysis, they analyse the situation that relates to the Spanish regions (Autonomous Communities, AACC) concerning budgetary expenditure intended for various environmental items. This work has some points in common with ours, since it uses the perspective of environmental expenditure. In fact, this work raises some doubts about the coherence between the political commitment to the Charter of Aalborg and Towns Campaign and European Cities for Sustainable Development and the actual implementation of local strategies for sustainable development economic support.

128Norway

Independently of the LA21 implementation, parallel experiences in policy decentralisation have been verified in Norway. The government in Norway transferred considerable powers in nature conservation management to local governments, hoping to facilitate a wider local involvement in conservation policy. Decentralisation has proven to be a success in welfare policy but is rather controversial in environmental policy. Conservation policy differs from welfare policy, as the first is marked by conflicting goals and interests between local and central governments. Some empirical studies show that local councils redefine national policy and implement management practices in a manner more attuned to local needs and interests (Falleth and Hovik, 2009). In 2009, the Norwegian Parliament decided to initiate a reform of the governance of protected areas. The reform establishes more than 40 local management boards with extensive decision-making authority over much of Norway’s protected areas. The boards have management authority over clusters of national parks, protected landscapes, and nature reserves. The reform was initiated in a situation of considerable conflict regarding protected areas, and implementation studies anticipate that the reform is likely to reduce conflict levels and increase the importance given to local user interests (Fauchald and Gulbrandsen, 2012).

Though Norway is usually considered a pioneer with respect to sustainable development, analyses have shown that this has not been the case with respect to Local Agenda 21. Still, Norwegian municipalities have strengthened their institutional capacity with respect to environmental policy, and have thereby strengthened their ability to follow up on the recommendations in Agenda 21. However, initially, it is the local environmental problems that have received the most attention rather than global environmental and development problems. Aall (2000) thinks that national environmental policy in Norway seems reluctant to face the global problems, leaving the municipalities with the great challenge of being the ‘engine’ in steaming up Norwegian environmental politics, and he raises some doubts as to whether the growing number of Local Agenda 21 initiatives in Norway will in fact adopt the global perspectives outlined by the Brundtland report and Agenda 21, or just keep on with a ‘business as usual’ environmental policy approach.

129Norwegian experiences on local environmental policy, Local Agenda 21 (LA21), local climate change mitigation (CCM) and local climate change adaptation (CCA) were compared, and conclusions pointed out that local CCA-like mainstream local environmental policy, unlike that of LA21 and local CCM, is exclusively framed in a local context and lacks the normative impetus for local action that LA21 and local CCM have had (Aall, 2012).

I. Methodology

In this work, we will try to verify the following hypotheses:

–The municipalities that adhere to the Local Agenda 21 devote more budgetary resources to expenditure functions related to the environment.

–The municipalities that adhere to the Local Agenda 21 promote greater citizen participation.

–The size of municipalities’ population allows for differentiation of particular patterns of behaviour in Spanish and Norwegian municipalities that adhere to the Local Agenda 21.

Since we have replicated similar analyses in Spanish and Norwegian municipalities, we are going to describe both samples individually.

Regarding the Spanish sample, the temporal scope covers the period 2002–2012. The geographic scope, before the application of the exclusion criteria, covers 100% of the Spanish national territory. The analytical work of this article is based on a database of our own construction, in which we have combined the data from the final budgets for 2002 and 2012 and the population of each municipality for the years studied.

Regarding the budget, data have been obtained from the website of the Ministry of Finance and Public Administration (http://serviciosweb.meh.es/apps/EntidadesLocales/). It is important to note that there was a change in the accounting rules of local governments that generated a difference in content of programs of environmental expenditure between 2002 and 2010. Since 2010, the accounting methodology has been homogeneous.

130In accordance with the Order of September 20, 1989, by which the structure of the budgets of local authorities is regulated, we have identified two spending sub-functions for the year 2002 included in the function 4.4 “Community Welfare”. This function includes all costs relating to activities and services aimed at improving the quality of life in general. It will be charged with costs derivatives maintenance, upkeep and operation of the services of treatment, supply and distribution of water; collection, disposal or treatment of waste; street cleaning; office of consumer information; protecting and improving the environment; cemeteries and burial services; slaughterhouses; markets; fairs and exhibitions, etc. The sub-functions typified include:

4.4.1 Treatment, supply and distribution of water.

4.4.2 Waste collection and street cleaning.

For this work, the variable environmental expenditure in 2002 is the sum of the costs incurred by the municipalities in the sub-functions 441 and 442. After 2010, a new sub-function was included in the functional classification of local budgets, the 17th policy “Environment”. This policy is present in budgets subsequent to 2010 (Order EHA / 3565/2008, of December 3, in which the structure of the budgets of local authorities is approved). The 17th policy includes four programs:

170. General administration of the environment.

171. Parks and gardens.

172. Protecting and improving the environment.

179. Other activities related to the environment.

Thus, in 2012 we included the 17th policy “Environment” and three additional programs which were incorporated into the 16th policy “Community welfare”:

161. Sanitation, supply and distribution of water.

162. Collection, disposal and treatment of waste.

163. Street cleaning.

Nevertheless, because the programs do not indicate the specific content of the expenses included in each program, to simplify the analysis, we used aggregate spending data as variable in analysis for the years 2002 and 2012 as well. Therefore, the concept of environmental expenditure 131is taken from the functional classification of municipal budgets, by reference to the sum of the sub-functions 441 and 442 for 2002 and the whole policy no.17 plus the programs 161, 162, and 163 in 2012. In total, a database has been designed with 11,857 records corresponding to those of local authorities that are in the budget database of the years 2002 and 2012. From this whole, a sample of 1,273 municipalities has been selected. To obtain this sample, we applied the following exclusion criteria on the whole of those of local authorities:

–Municipalities without environmental expenditure in 2002

–Municipalities without environmental expenditure in 2012

–Local government entities without associated population (Other municipalities: Councils, Commonwealths, Counties, etc.)

Of these 1,273 municipalities that collected environmental cost in their budgets, the experimental group is initially composed of 161 Spanish municipalities that in 2002 had adhered to the AL211. Finally, after we applied the exclusion criteria, 1,273 municipalities, of which 143 belong to the experimental group (LA21) and the remaining 1,130 to the control group, were included in our study sample.

Regarding the Norwegian sample, the temporal scope covers the period 1999–2013. The analysis here focuses on longer-term effects. The first measurement is taken around the time of the “Fredrikstad-Declaration”. 61 percent of all the municipalities signed the agreement in 1998. The second measurement occurs fourteen years later, except for turnout which is measured at the local elections in 2011. The geographic scope covers 100% of the Norwegian municipalities. No exclusion criteria have been applied.

The analytical work of this article is based on a database of our own construction, in which we have combined the data from the final budgets for 1999 and 2013 and the population of each municipality for the years studied. The Norwegian database also underwent some statistical and functional changes in the definition of variables in 2000:

132–Environment: Gross expenditure devoted to environmental measures and administration of those for the period 1991–2000 and to physical planning, cultural heritage and environmental measures for the period 2001–2013.

–Renovation: Gross expenditure devoted to collection and treatment of waste for the period 1982–2000 and collection and treatment of waste + water for the period 2001–2013.

–Water: Gross expenditure devoted to water and waterworks for the period 1982–2000 and production and supply of water for the period 2001–2013.

Table 1 provides information on the coverage of both samples with respect to the whole, in terms of number of municipalities, population and environmental expenditures.

|

No. Municipalities |

No. Inhabitants |

M1 Expend. |

M2 Expend. |

M3 Expend. |

M4 Expend. |

Voter Turnout |

||

|

Norway |

1999 |

428 |

4 478 497 |

285 650 |

5 170 810 |

2 150 980 |

2 734 180 |

62,95 |

|

Non LA21 |

166 |

823 114 |

60 370 |

863 700 |

377 190 |

426 140 |

63,99 |

|

|

MS/L |

56 |

588 971 |

22 890 |

551 370 |

251 840 |

276 640 |

60,14 |

|

|

S |

110 |

234 143 |

37 480 |

312 330 |

125 350 |

149 500 |

65,95 |

|

|

LA21 |

262 |

3 655 383 |

225 280 |

4 307 110 |

1 773 790 |

2 308 040 |

62,29 |

|

|

MS/L |

154 |

3 374 739 |

173 600 |

3 949 840 |

1 662 380 |

2 113 860 |

59,78 |

|

|

S |

108 |

280 644 |

51 680 |

357 270 |

111 410 |

194 180 |

65,88 |

|

|

2013 |

428 |

5 109 056 |

5 531 750 |

24 759 617 |

4 799 236 |

14 428 631 |

66,17 |

|

|

Non LA21 |

166 |

887 525 |

980 657 |

4 422 379 |

960 164 |

2 481 558 |

67,14 |

|

|

MS/L |

56 |

662 663 |

651 106 |

3 017 418 |

643 273 |

1 723 039 |

64,32 |

|

|

S |

110 |

224 862 |

329 551 |

1 404 961 |

316 891 |

758 519 |

68,58 |

|

|

LA21 |

262 |

4 221 531 |

4 551 093 |

20 337 238 |

3 839 072 |

11 947 073 |

65,56 |

|

|

MS/L |

162 |

3 979 346 |

4 098 685 |

18 594 764 |

3 508 056 |

10 988 023 |

63,70 |

|

|

S |

100 |

242 185 |

452 408 |

1 742 474 |

331 016 |

959 050 |

68,56 |

|

|

Spain |

2002 |

1273 |

31 931 391 |

2 839 357 851 |

2 839 357 851 |

770 658 560 |

2 068 699 291 |

54,58 |

|

Non LA21 |

1130 |

16 819 579 |

1 352 919 098 |

1 352 919 098 |

444 637 993 |

908 281 104 |

55,47 |

|

|

MS/L |

501 |

14 469 959 |

1 173 778 447 |

1 173 778 447 |

357 592 886 |

816 185 562 |

50,34 |

|

|

S |

629 |

2 349 620 |

179 140 650 |

179 140 650 |

87 045 108 |

92 095 543 |

59,58 |

|

|

LA21 |

143 |

15 111 812 |

1 486 438 753 |

1 486 438 753 |

326 020 566 |

1 160 418 187 |

47,57 |

|

|

MS/L |

135 |

15 083 372 |

1 483 232 627 |

1 483 232 627 |

325 059 233 |

1 158 173 394 |

46,74 |

|

|

S |

8 |

28 440 |

3 206 126 |

3 206 126 |

961 333 |

2 244 793 |

61,50 |

|

|

2012 |

1273 |

36 169 893 |

1 293 248 077 |

6 052 526 029 |

863 538 357 |

3 895 739 595 |

51,25 |

|

|

Non LA21 |

1130 |

19 700 568 |

588 066 873 |

2 977 055 462 |

511 321 828 |

1 877 666 761 |

52,18 |

|

|

MS/L |

501 |

16 805 888 |

517 978 946 |

2 608 540 908 |

413 697 420 |

1 676 864 542 |

48,45 |

|

|

S |

629 |

2 894 680 |

70 087 927 |

368 514 555 |

97 624 408 |

200 802 219 |

55,17 |

|

|

LA21 |

143 |

16 469 325 |

705 181 204 |

3 075 470 567 |

352 216 529 |

2 018 072 834 |

43,91 |

|

|

MS/L |

135 |

16 434 197 |

704 327 273 |

3 068 568 619 |

350 987 442 |

2 013 253 904 |

43,15 |

|

|

S |

8 |

35 128 |

853 931 |

6 901 948 |

1 229 087 |

4 818 930 |

56,77 |

MS/L: Medium-Sized and Large Municipalities – S: Small Municipalities

Tab. 1 – Samples’ Characteristics.

133The coverage of the Norwegian sample is 100% in terms of territorial coverage and population. The population included in the experimental group represents 82% and 83% of the national population in 1999 and 2013 respectively. The coverage of the Spanish sample is around 81% and 77% in terms of population in 2002 and 2012 respectively. The experimental group in Spain represents 47% and 46% of population included in the sample in the years 2002 and 2012.

Apart from the usual variables (G and T) characteristic of all DiD models, the five models built for this work include two control variables: total budget expenditure (final budget) and population

For the treatment of data and application of statistical techniques, software packages, SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences), SAS (Statistical Analysis Software) and Eviews 8 have been used. The specific concepts included in the dependent variables of all econometric models, for the initial and final periods, are displayed in Table 2.

|

MODEL |

COUNTRY |

T=0 |

T=1 |

|

Model 1 |

Spain |

4.4.1 Treatment, supply and distribution of water. 4.4.2 Waste collection and street cleaning |

170. General administration of the environment. 171. Parks and gardens. 172. Protecting and improving the environment. |

|

Norway |

Environmental measures and administration |

Physical planning, cultural heritage and environmental measures |

|

|

Model 2 |

Spain |

4.4.1 Treatment, supply and distribution of water. 4.4.2 Waste collection and street cleaning |

170. General administration of the environment. 171. Parks and gardens. 172. Protecting and improving the environment. 179. Other activities related to the environment. 161. Sanitation, supply and distribution of water. 162. Collection, disposal and treatment of waste. 163. Street cleaning. |

|

Norway |

– Environmental measures and administration – Expenditure devoted to collection and treatment of waste – Expenditure devoted to water and waterworks |

– Physical planning, cultural heritage and environmental measures – Collection and treatment of waste + water – Production and supply of water |

|

| 134

Model 3 |

Spain |

4.4.1 Treatment, supply and distribution of water. |

161. Sanitation, supply and distribution of water. |

|

Norway |

Expenditure devoted to water and waterworks |

Production and supply of water |

|

|

Model 4 |

Spain |

4.4.2 Waste collection and street cleaning |

162. Collection, disposal and treatment of waste. 163. Street cleaning. |

|

Norway |

Expenditure devoted to collection and treatment of waste |

Collection and treatment of waste + water |

|

|

Model 5 |

Spain |

Turnout as percentage of total eligible voters recorded in the censuses at the municipal elections |

Turnout as percentage of total eligible voters recorded in the censuses at the municipal elections |

|

Norway |

Turnout as percentage of total eligible voters recorded in the censuses at the municipal elections |

Turnout as percentage of total eligible voters recorded in the censuses at the municipal elections |

Tab. 2 – Definition of dependent variables.

Difference in Differences treatment effects (DiD) have been widely used when the evaluation of a given intervention entails the collection of panel data or repeated cross sections. DiD integrates the advances of the fixed effects estimators with the causal inference analysis, when unobserved events or characteristics confound the interpretations (Angrist, J.D. and Pischke, J., 2009).

Despite the existence of other plausible methods based on the availability of observational data for quasi-experimental causal inference–i.e., matching methods, instrumental variable, regression discontinuity– DiD estimations offer an alternative, reaching the unconfoundedness by controlling for unobserved characteristics and combining them with observed or complementary information. Additionally, the DiD is a flexible form of causal inference, because it can be combined with some other procedures, such as the Kernel Propensity Score and the quintile regression (Villa, 2012).

For econometric assessment, the impact of the Local Agenda 21 on spending, the next base regression is used (Pérez López, C. and Moral Arce, I., 2015):

Y = a0 + a1G + a2T + a3G*T + b1X1 + b2X2 + e [1]

135Y is the environmental expenditure.

G is the dummy variable that distinguishes the group (treatment or control).

T is the dummy variable defining the baseline and the end-line.

G x T is the interaction between the dummy variables G and T; its estimated coefficient is the value a3, statistical of difference in differences, which is that which assesses the impact of LA21 spending on sustainability.

X1 is a control variable corresponding to Total Budget.

X2 is a control variable corresponding to Population.

e represents the error term.

Thus, the final budgets of the two years of comparison and the population of the municipalities of the sample have also been included as independent variables, along with the dummy variables referred to above, in the estimates. Because we included a control variable concerning the population in the model, we utilised absolute values, and non per capita values, in all estimates.

In order to know if population size of municipalities introduces a differential impact of LA21 on environmental expenditure and citizen participation, we have solved all models for the whole sample and for two segmented sub-samples. This segmentation distinguishes between two groups– small and medium-sized or large municipalities. We used the median population to classify every municipality into one of these two groups.

Finally, we conclude this section with an argument in support of measuring citizen participation by means of voter turnout. The issue of adhering to LA21 taps into the general debate in electoral research pertaining to the salience of the so-called ‘new’ politics. This new politics confronts the New Left, which is mobilising post-material issues such as environmentalism and liberal universalism, versus the New Right, which is mobilising anti-environmentalism and communitarian values. Many researchers see this as a new split based on values (Kriesi, 2010). The point is that the voters that are motivated by these issues are less motivated to turn out and cast their votes by the traditional Left-Right divide based on state-market, religiosity and urban-rural residence and will therefore tend to abstain if the issues pertaining to the ‘new’ politics 136are not activated within the political system (Crepaz, 1990). Thus, we may hypothesise that the local political decision of adhering to the LA21 has potentially led to higher turnout rates in these municipalities.

I. Results

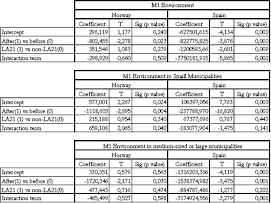

The first model attempts to evaluate the impact of LA21 on general environmental expenditures. Results of this model are presented in Tab. 3.

Tab. 3 – Model 1 General Environmental Expenditures.

This model offers negative and statistically significant values for T variable in both countries. The interaction term coefficient is statistically significant for small Norwegian municipalities and for large Spanish municipalities, although in Spanish municipalities the sign is negative. Nevertheless, Spanish data are quite dissimilar in between the origin and the end of the period of analysis, so the results of this model are not very reliable with regard to Spanish municipalities.

137Model 2 reflects the most comprehensive perspective regarding the impact of LA21 on environmental expenses. The dependent variable used in this model includes the general environmental expenditures, as well as those related to water and waste/renovation.

After running the model for the whole sample, we only obtained positive and statistically significant impact for Spanish municipalities. But, when the model was solved for large and small towns independently, the results revealed a very uneven impact of LA21 on the environmental expenses in every town size group and in every country.

Positive and statistically significant impacts are concentrated in small Norwegian municipalities and in large Spanish municipalities.

Tab. 4 – Model 2 Total Environmental Expenditures.

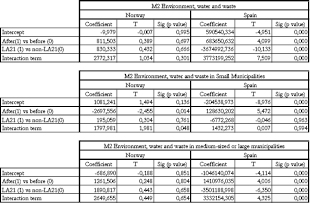

Models 3 and 4 estimate the impact of LA21 on water and waste expenses independently considered. Model 3 does not confirm a positive impact of LA21 on water expenditures at all. However, Model 4 offers the most positive data regarding the impact of LA21 on waste expenses. This model gives similar results to those obtained with Model 2 but, in addition, confirms a positive impact for the full sample of Norwegian municipalities.

138

Tab. 5 – Model 3 Water Expenditures.

Tab. 6 – Model 4 Waste Expenditures.

139As we saw in previous tables, statistically significant impacts are concentrated in small Norwegian municipalities while in large Spanish municipalities. These specific concentrations respond to particular circumstances of large and small municipalities in each country.

Regarding Spanish municipalities, even though LA21 processes are mainly locally regulated, regional governments have played a crucial role in promoting their implementation. Most Autonomous Communities offered financial help to local governments with that specific aim, and in many cases, they also gave technical and methodological support. Some regional governments, such as the Basque Country, Navarre and Catalonia, carried out their own sustainable development plans and strategies, or their own Agendas 21 (Aguado et al. 2007). All these financial and technical aids are usually addressed to small municipalities and the regional budgets reflect their economic impact. Thus, local budgets in small municipalities do not give a complete picture of the whole amount of money devoted to environmental expenses.

The finding that LA21 has had an effect in the smaller Norwegian municipalities and not in the larger ones is in accordance with the general finding in Jenssen and Robertsen (2015). Although all Norwegian municipalities, regardless of size, are expected to deliver the same number of public services and 80 percent of municipal tasks are decided by the national parliament, they find that size has a significant impact on setting local priorities. Based on data from the national database on municipal budgets and services (KOSTRA), they find that both the ability and willingness to set their own priorities is stronger among the smaller municipalities than among the larger ones. We have corroborated the findings in Jenssen and Robertsen (2015) as to the impact of the size of the municipalities. There is a substantial difference in what is called “free income” per capita between small and large municipalities. “Free income” consists of two types of municipal income: Free budget involves transfers from the state level (i.e. transfers that are not earmarked) and municipal taxes. We also find that the variation is much greater among the smaller municipalities and we see that the results are consistent over time. Our findings show that the ability to set local priorities is greater among the smaller municipalities and that their leverage per capita is higher.

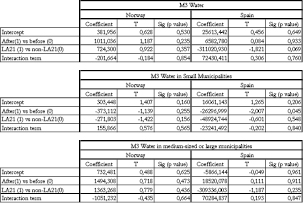

Finally, Model 5 does not evaluate the impact of LA21 on environmental expenditures but on citizen participation. As we did not have 140specific data about the real participation of citizens in participatory processes related to environmental management at a local level, we used the voter turnout in local elections as a proxy variable.

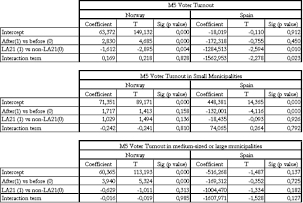

Tab. 7 – Model 5 Voter Turnout.

The results obtained reject the theoretically positive impact of LA21 on citizen participation in both countries. The whole sample resolution of the model for Spanish municipalities gives a negative, though statistically significant, impact. Thus, it seems that those Spanish municipalities that adhered to LA21 present higher probability of showing lower citizen participation.

Conclusions

In this section, we will go over the research questions, objectives, and assumptions stated in the introduction and methodology sections. First, we formulated three research questions regarding budgetary resources 141devoted to environmental expenditures, citizen participation, and the influence of population size in both aspects.

The literature review carried out in the introduction section has confirmed the relevance of those questions and the lack of response in the specialised economic literature. Thus, the main objective of this paper is to compare the behaviour of Norwegian and Spanish municipalities and find differences and similarities with respect to these questions.

In order to verify three hypotheses related to the original research questions, we used five econometric models supported by five specific objectives.

Our results confirmed two of these original hypotheses. First, the results from Model 2 clearly show that, in a broad sense, the municipalities that adhered to the Local Agenda 21 devoted more budgetary resources to expenditure functions related to the environment in both countries. Second, although this hypothesis was only partially confirmed, the population size of the municipalities did exert a significant influence on the evolution of environmental expenditure. Nonetheless, this hypothesis is fully confirmed for a specific type of environmental expenditure, the waste expenses. Model 4 ratifies the positive impact of LA21 on waste expenses in both countries. The strongest causal relationships were found in small Norwegian towns and in large Spanish municipalities. Thus, hypotheses 1 and 3 were confirmed by means of the Models 2 and 4.

Nevertheless, Model 5 negated the positive impact of LA21 on citizen participation, so it became impossible to confirm hypothesis number 2. This result ratifies some critical papers that questioned the success of LA21 in promoting citizen participation and emphasised the disparities among municipalities and the influence of organisational aspects.

Some methodological limitations of this study should be noted, although in our opinion, in no case did these limitations question the validity of the results:

–The change in the Spanish accounting methodology of local authorities causes a break in the time series of environmental spending. The Norwegian database is also influenced by the statistical change in the functional content of environmental programs of expenditure in 2000. However, since this circumstance affects all municipalities, we consider that this does not 142–invalidate or limit the effectiveness of the DiD analysis that was carried out. The model compares the experimental group with a control group subject to identical conditions, except for the adherence to the LA21.

–Most Spanish municipalities that adhered to the LA21 are large or medium-sized towns, so the low number of municipalities included in the group of small towns restricts the representativeness of analyses based on that group.

–Time-periods of analysis are not exactly the same for Spain and Norway, although they are similar. While in Spain we studied the period 2002–2012, in Norway we used the years 1999 and 2013 as initial point and end-line respectively. The differences in the beginning were motivated by the start of national plans supporting LA21 (Fredrikstad-Declaration in Norway, 1998; the Sustainable Development Strategy in Spain, 2000). Despite the difference, the time-period in both countries is long enough to carry out an analysis focused on long-term effects.

–With this approach, we are leaving out the issue of efficiency in spending. Efficiency assessment would be a critical issue if we were evaluating the effectiveness of LA21 implementation, but not for the objective pursued in this paper.

Regardless of these limitations, we consider it appropriate to clarify that the aim of this paper is not to evaluate the success of local governments in implementing Local Agenda 21. We simply try to verify the causal relationship between LA21 adherence and environmental spending. For that reason, other determinant variables for environmental spending have not been included in the econometric models. The control variables included in the models aim to eliminate the bias exerted by the largest municipalities.

As for the policy implications, it should be noted that increasing budgetary allocations for environmental expenditure in a period of economic crisis and budgetary constraints, especially in Spain, implies a high commitment to the objectives of Agenda 21 in terms of promoting a model of sustainable development. Our work shows that, in the municipalities adhering to the LA21, this effort has been even greater. 143However, we must not forget that the environmental commitment has also meant an additional way for recovery of the role and legitimacy of local governments. In this sense, it is expected that the economic recovery will accentuate the effect of the innovation process in managing local governments. This should be reflected in a higher intensity of environmental spending in the coming years.

This research focuses only on the environmental expenses covered with decentralised budgets of local governments, so it does not show the whole picture. Obviously, upper tiers of governments at regional or national levels play an important, sometimes decisive, role in the whole environmental expenditure, but only local governments are the subject of interest in this particular study.

The first line of progress in this investigation will be marked by the extension of the temporal scope. Once we have outlined the methodological aspects, it is relatively easy to enlarge the database by adding new data from recent years as soon as they are available. In this way, a longer period of analysis will help to consolidate the results obtained.

The second line of investigation derived from this work will focus on the replication of these analyses with dependent variables that reflect real outcomes of LA21 environmental programs. The combination of expenditure and outcomes will allow us to widen the scope of the analysis by including the efficiency analysis of environmental expenses.

Finally, we finish by emphasising that Models 2 and 4 showed the most reliable and consistent results. Both models present positive and statistically significant impact of LA21 on municipal expenses in environmental programs, especially in those related with waste management and renovation. These positive results appear concentrated in small Norwegian towns and in the medium-sized and large Spanish municipalities. Thus, we see that the political commitment, expressed by the Spanish and Norwegian municipalities in signing the Aalborg Charter and adhering to the LA21, is supported with increased resources for environmental programs.

144References

Aall C. (2000), “Municipal Environmental Policy in Norway: From “mainstream” policy to “real” Agenda 21?” Local Environment, 5(4), p. 451–465.

Aall C. (2012), “The early experiences of local climate change adaptation in Norwegian compared with that of local environmental policy, Local Agenda 21 and local climate change mitigation”, Local Environment, 17(6–7), p. 579–595.

Adolfsson S. (2002), “Local Agenda 21 in Four Swedish Municipalities: A Tool towards Sustainability?”, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 45(2), p. 219–244.

Agger A. (2010), “Involving citizens in sustainable development: evidence of new forms of participation in the Danish Agenda 21 schemes”, Local Environment, 15(6), p. 541–552.

Aguado I., Barrutia J.M., and Echebarria M. (2007), “La Agenda 21 Local en España”, Ekonomiaz: Revista vasca de economía, 64, p. 174–213.

Aguado I., and Echebarría C. (2004), “El gasto medioambiental en las Comunidades Autónomas y su relación con la Agenda Local 21: estudio mediante el empleo del análisis de correspondencias”, Estudios Geográficos, 65(255), p. 195–228.

Angrist J.D. and Pischke J., (2009), Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Barrutia J. M., and Echebarria C. (2011), “Explaining and Measuring the Embrace of Local Agenda 21s by Local Governments”, Environment and Planning A, 43(2), p. 451–469.

Bjørnæs T. and Norland I.T. (2002), “Local Agenda 21: Pursuing Sustainable Development 43 at the Local Level”, in Lafferty W.M., Nordskag M. and Aakre, H.A. (eds), Realizing Rio in Norway. Evaluative Studies of Sustainable Development, p. 43–61. Oslo: Program for Research and Documentation for a Sustainable Society (ProSus).

Brunet Estarellas P. J., Almeida García F. and Coll López M. (2005), “Agenda 21: Subsidiariedad y Cooperación a favor del Desarrollo Territorial Sostenible”, Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, (39), p. 423–446.

Cole R. J. and Valdebenito M. J. (2013), “The importation of building environmental certification systems: international usages of BREEAM and LEED”, Building Research and Information, 41(6), p. 662–676.

Crepaz M.M.L. (1990), “The impact of party polarization and postmaterialism 145on voter turnout: A comparative study of 16 industrial democracies”, European Journal of Political Research, 18, p. 183–205.

Devuyst D. (1999), “Sustainability assessment: the application of a methodological framework”, Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management, 1(4), p. 459–487.

Echebarria C., Barrutia J. M. and Aguado, I. (2004), “Local Agenda 21: Progress in Spain”, European Urban and Regional Studies, 11(3), p. 273–281.

Eckerberg K. and Forsberg B. (1998), “Implementing agenda 21 in local government: The Swedish experience”, Local Environment, 3(3), p. 333–347.

Hovden E. and Torjussen S. (2002), “Environmental Policy Integration in Norway”, in Lafferty W.M., Nordskag M. and Aakre H.A (eds), Realizing Rio in Norway. Evaluative Studies of Sustainable Development, Oslo: Program for Research and Documentation for a Sustainable Society (ProSus), p. 21–41.

European Sustainable Cities Platform–AALBORG +10 2004. (s. f.). Retrieved from http://www.sustainablecities.eu/events/aalborg-10-2004/

Evans B. and Theobald K. (2003), “Policy and Practice LASALA: Evaluating Local Agenda 21 in Europe”, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 46(5), p. 781–794.

Falleth E. I., and Hovik S. (2009), “Local government and nature conservation in Norway: decentralisation as a strategy in environmental policy”, Local Environment, 14(3), p. 221–231.

Fauchald O. K. and Gulbrandsen L. H. (2012), “The Norwegian reform of protected area management: a grand experiment with delegation of authority?” Local Environment, 17(2), p. 203–222.

Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias-FEMP, and Observatorio de la Sostenibilidad en España-OSE (Eds.) (2013), 20 años de Políticas Locales de Desarrollo Sostenible en España. Madrid: Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias (FEMP).

Foh Lee K. (2001), “Sustainable tourism destinations: the importance of cleaner production”, Journal of Cleaner Production, 9, p. 313–323.

Font N. and Subirats J. (2000), Local y sostenible: la Agenda 21 Local en España, Icaria Editorial.

Haapio A. and Viitaniemi P. (2008), “A critical review of building environmental assessment tools”, Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 28(7), p. 469–482.

Hernández Aja A. (2003). Informe sobre los indicadores locales de sostenibilidad utilizados por los municipios españoles firmantes de la Carta de Aalborg. Retrieved from http://www.medioambientecantabria.es/documentos_contenidos/14940_1.511.pdf

146Hess D. and Winner L. (2007), “Enhancing Justice and Sustainability at the Local Level: Affordable Policies for Urban Governments”, Local Environment, 12(4), p. 379–395.

Hidalgo L. A. (2008), “La implantación de la Agenda 21 Local en las diferentes Comunidades Autónomas: Orígenes, evolución y valoración global del proceso”, Revista de fomento social, (250), p. 233–274.

Jiménez Herrero L. M. (2008), Sostenibilidad local: una aproximación urbana y rural. Observatorio de la Sostenibilidad en España. Retrieved from http://www.magrama.gob.es/en/ceneam/recursos/materiales/sostenibilidad-local.aspx

Joas M. and Grönholm B. (2004), “A comparative perspective on self-assessment of Local Agenda 21 in European cities”, Boreal Env. Res., 9(6), p. 499–507.

Kriesi H. (2010), “Restructuration of Partisan Politics and the Emergence of a New Cleavage Based on Values”, in Enyedi Z., Bornschier S., Deega-Krause K. and Dolezal M. (2010) (Guest editors special issue) The Structure of Political Competition in Western Europe, West European Politics, 33 (3), p. 673–685.

Lafferty W. M. and Eckerberg K. (2013), From the Earth Summit to Local Agenda 21: Working Towards Sustainable Development. Routledge.

Lafferty W. M., Knudsen J. and Larsen O. M. (2007), “Pursuing sustainable development in Norway: the challenge of living up to Brundtland at home”, European Environment, 17(3), p. 177–188.

Lawrence D. P. (1997), “PROFILE: Integrating Sustainability and Environmental Impact Assessment”, Environmental Management, 21(1), p. 23–42.

Martínez M. and Rosende S. (2011), “Participación ciudadana en las agendas 21 locales: cuestiones críticas de la gobernanza urbana”, Scripta Nova: Revista electrónica de geografía y ciencias sociales, (15), p. 348–386.

Moralejo I. A., Legarreta J. M. B. and Miguel, C. E. (2007), “La Agenda 21 Local en España”, Ekonomiaz: Revista vasca de economía, (64), p. 174–213.

Nijkamp P. and Pepping G. (1998), “A Meta-Analytical Evaluation of Sustainable City Initiatives”, Urban Studies, 35(9), p. 1481–1500.

Observatorio de la Sostenibilidad. (2014), Informe Sostenibilidad en España 2014. Retrieved from http://www.observatoriosostenibilidad.com/sostenibilidad-en-espana-2014/

Papadopoulos A. M. and Giama E. (2009), “Rating systems for counting buildings’ environmental performance”, International Journal of Sustainable Energy, 28(1–3), p. 29–43.

Pérez López C. and Moral Arce I. (2015), Técnicas de evaluación de impacto. Madrid, Spain: Garceta, Grupo Editorial.

147Poveda C. A. and Lipsett M. (2011), “A Review of Sustainability Assessment and Sustainability/Environmental Rating Systems and Credit Weighting Tools”, Journal of Sustainable Development, 4(6), p. 36–55.

Prado M. and García I. M. (2009), “Agenda 21 Local: Efecto de las estructuras organizativa y política en la organización social de la Agenda 21 Local”, Revista de economía mundial, (21), p. 195–226.

Rutherfoord R., Blackburn R.A. and Spence L.J. (2000), “Environmental management and the small firm”, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 6(6), p. 310–326.

Stakeholder Forum for a Sustainable Future. (2012), Review of implementation of Agenda 21 and the Rio Principles. Retrieved from http://www.stakeholderforum.org/index.php/our-publications-sp-1224407103/reports-in-our-publications/410-undesa-synthesis-review-of-agenda-21-and-the-rio-principles.

Thomas I. G. (2010), “Environmental policy and local government in Australia”, Local Environment, 15(2), p. 121–136.

Valentin A. and Spangenberg J. H. (2000), “A guide to community sustainability indicators”, Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 20(3), p. 381–392.

Villa J. (2012), Simplifying the estimation of difference in differences treatment effects with Stata (MPRA Paper). University Library of Munich, Germany. Retrieved from http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/pramprapa/43943.htm

1 Data obtained from the study of Hernández Aja, A. (2003). According to this study, 409 municipalities had signed the Aalborg Charter by 2002. 189 municipalities confirmed their commitment to the Aalborg Charter in a survey. 143 of them appear in our database with environmental costs in their budgets.