The Giunti Press, Gilles Ménage, Dante, and the Invention of Medieval Italian Literature

- Publication type: Journal article

- Journal: Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes - Journal of Medieval and Humanistic Studies

2021 – 1, n° 41. varia - Author: Nussmeier (Antony)

- Abstract: Les annotations que Gilles Ménage, italianiste français du XVIIe siècle, a portées sur un exemplaire de l’édition princeps du De vulgari eloquentia de Dante (1577) reflètent « l’invention » d’une littérature médiévale italienne contemporaine de Dante. L’importance du traité de Dante pour la construction d’un canon médiéval est ici mise en lumière grâce à l’étude de ces annotations et des catégorisations de Pietro Bembo.

- Pages: 205 to 222

- Journal: Journal of Medieval and Humanistic Studies

- CLIL theme: 4027 -- SCIENCES HUMAINES ET SOCIALES, LETTRES -- Lettres et Sciences du langage -- Lettres -- Etudes littéraires générales et thématiques

- EAN: 9782406119968

- ISBN: 978-2-406-11996-8

- ISSN: 2273-0893

- DOI: 10.48611/isbn.978-2-406-11996-8.p.0205

- Publisher: Classiques Garnier

- Online publication: 07-07-2021

- Periodicity: Biannual

- Language: English

- Keyword: Bembo, Ménage, poésie médiévale italienne, Dante, De vulgari eloquentia

The Giunti Press, Gilles Ménage,

Dante, and the Invention

of Medieval Italian Literature

In the seventeenth century, prolific French Italianist Gilles Ménage had in his possession a copy of the printed editio princeps of Dante’s Latin treatise De vulgari eloquentia (c. 1303/4-1305), which had been edited and published from Paris in 1577 by the Florentine fuoriuscito Jacopo Corbinelli at the court of Henry iii1. Now known as the Mannheim copy2, the book contains numerous annotations in the hand of Ménage (1613-1692), who was renowned for his studies of Italian, Le origini della lingua italiana (1669; 1685) and Mescolanze (1678), as well as for his works on French, Les origines de la langue Françoise (1650), Observations sur la langue françoise (1672), and Dictionnaire étymologique ou origines de la langue françoise (1694), not to mention his much-lauded Greek and Latin literary scholarship, legal studies, works of history and biography, and modern editions of French and Italian authors. Ménage enjoyed an international reputation exemplified by his voluminous epistolary correspondence and his membership in the Florentine Accademia della Crusca. Even today he is considered a pioneer in the study of linguistics and etymology3. Much of Ménage’s work focused on the origins of French and Italian as vernacular languages, and so his interest in Dante’s multiform Latin treatise is understandable: its study of the origins of language itself, the 206European vernaculars, the Italian vernaculars, and Italian lyric poetry, reflect many of the French scholar’s own interests. (Ménage also wrote verse in Latin, Greek, French, and Italian.) Corbinelli’s own (errant) hypothesis that Dante wrote the treatise from Paris, along with the implied, osmotic transfer of vernacular Italian’s glory to contemporary debates about the status of vernacular French at the court of Henry III, made Ménage’s enthusiasm for the DVE all the more appropriate, for its emergence in France in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had come about in the midst of that country’s own ongoing question de la langue4.

This essay will consider notions of continuity and rupture with medieval Italian literature, and will discuss Ménage’s annotations to the 1577 DVE, as well as the paratext of the 1527 anthology of medieval poetry Sonetti et canzoni di Diversi Antichi Autori Toscani in Dieci libri raccolte (known as the Giuntina di rime antiche) as an example of the sixteenth-century’s humanistic impulses and antiquarianism. Though the language of the anthology is very much in line with sixteenth-century modes of thought, there are certain terms that, like Gilles Ménage’s annotations to the 1577 DVE, hark all the way back to Dante Alighieri and his militant criticism, and so the book is a paradox demonstrating both continuity and rupture with the medieval tradition. In looking at the 1577 edition and Ménage’s annotations, particularly his references to Pietro Bembo, we shall see that it was already clear in the seventeenth century that Bembo had accepted Dante’s history of early Italian vernacular lyric. Dante and his DVE laid the groundwork for Bembo’s Prose della volgar lingua, indeed the groundwork for many sixteenth- and seventeenth-century conceptions of medieval Italian poetry. (I would add that Dante’s reflections even prepared the way for our own, twenty-first-century conceptions of the Italian canon). We come to understand that this is not entirely novel, and that seventeenth-century letterati, such as Ménage, recognized Dante’s crucial role in the formation of early modern perspectives on Italian medieval vernacular poetry. Part of our task is not just to examine how early moderns discussed and categorized what we now call medieval literature, but to explore the very roots of the “invention” 207of Italian literature that led to those categorizations, which I locate much earlier in Dante’s De vulgari eloquentia.

What did the study of “medieval” literature look like precisely at the “end of history,” that is, the first quarter of the sixteenth century? How was medieval Italian poetry categorized on the eve of the Cinquecento’s own “memorable event,” the sack of Rome against whose backdrop was published the Giuntina di rime antiche? In their own invention of medieval literature, sixteenth-century Italian letterati took their cues from an earlier period. The sixteenth-century editors of the Giuntina di rime antiche categorized the non-Petrarchan and pre-Dantean medieval poetry as ancient statues to be dusted off, labeling much of pre-Dantean poetry “rough.” Though the archaeological metaphor is a novelty and derives from the regnant antiquarianism of the times, the reference point and touchstone, I argue, is nevertheless medieval itself, the product of rhetorical categories crafted by Dante in the DVE, especially in his trope of city versus country, and that his own invention of Italian literary culture set the tone for the Renaissance and early modern reception of medieval Italian lyric.

In this contribution, I will be discussing three primary texts. The first is Dante’s aforementioned Latin treatise the De vulgari eloquentia (c. 1303/1304-1305) and its 1577 Latin-language editio princeps. The question of its fortune is complicated, and we will recall that the DVE was never finished; never circulated widely; and was considered “sepolto e incognito” for nearly two centuries, from the time of its composition until its reemergence in Florence at the hands of Giangiorgio Trissino in the midst of the questione della lingua around 1510. Except for traces of it that appear in the work of various humanists and even in some manuscript anthologies of medieval Italian poetry, in those two-hundred years the DVE was nearly unknown5. The Italian translation was published first in 1529 by Trissino himself, while the editio princeps in Latin had to wait nearly fifty more years for Corbinelli’s edition. Elements or descriptions of the treatise can be found also in earlier manuscript anthologies of medieval Italian poetry, such as Chigiano L.VIII.306 from the 1360s/1370s, and in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Vita di Dante, but it was not widely read – or read at all – for nearly two centuries. Despite 208this, one notable copy of the 1577 editio princeps, now in Mannheim and once owned by Ménage, contains a number of annotations that point to the relative success of the DVE in dictating the terms with which sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian letterati grappled with medieval literature. Though the treatise is premised on discussion of the nobility of vernacular Italian as a poetic language, the DVE is also a work of semiotics, theology, rhetoric, history, literary criticism, and much else. Dante reviews the origins of human speech, the defects of all Italian vernaculars, and proposes an allegorical or aspirational vulgare illustre as the ultimate governor of the deficient forms of Italian. He also cites his preferred poets, as well as anti-models, in what amounts to a virtual anthology of medieval poetry. Most important, it is my contention that in the DVE he sets the rhetorical terms with which we discuss medieval Italian poetry.

The second text is Pietro Bembo’s Prose della volgar lingua, a work whose structure is typically humanistic, set up as a conversation between Federigo Fregoso, Ercole Strozzi, Carlo Bembo – Pietro’s brother – and Giulio de’ Medici, Duke of Nemours and the future Pope Clement VII. In the Prose, Pietro Bembo details his own history of the “volgar lingua” – vernacular Italian, in particular the Tuscan variety – that is in contrast to other theses regarding the proper resolution to the questione della lingua. Published in 1525, it was originally conceived decades earlier and was itself revised heavily after Pietro Bembo came across the DVE, a copy of which he had made for his personal study6. Finally, I will consider the anthology of medieval poetry Sonetti et canzoni di Diversi Antichi Autori Toscani in Dieci libri raccolte, published by the Giunti brothers of Florence and known to critics as the Giuntina di rime antiche. The book contains nearly 300 poems divided into eleven books: four with poems by Dante; one each with the poems of Cino da Pistoia, Guido Cavalcanti, Dante da Maino, and (Fra) Guittone d’Arezzo; a book comprised by an anthological section (IX: from Trecentisti to Federico II); a book devoted to ‘unattributed poems’ (which are, in fact, attributed in many cases); and a final book to three sestine and various rime di corrispondenza. The collection’s heterogeneity obscures the preponderance of Dante 209and the poets of the DVE: in fact, the triad of Tuscan poets composed of Dante, Cino da Pistoia and Guido Cavalcanti account for over half of the poems. In addition to the collection’s purposeful organization (the first three books are structured on the basis of the DVE: Dante, Cino da Pistoia, Guido Cavalcanti), the single source used for many of these poets’ lyric was the mid-fourteenth-century philo-Stilnovist MS Vaticano Chigiano L.VIII.305 and confirms its organicity7. The Giunti volume is anti-Bembian on the surface, especially in its promotion of Dante instead of Petrarca as a poetic model, but Bembian, for example, in its acceptance of Bembo’s orthographic and stylistics proposals that hark back to Petrarca.

Mezzi Tempi and the ‘invention’

of medieval Italian literature

As in other national literatures, the term “medieval, Middle Ages” – medioevo or mezzi tempi – began to be bandied about in the Italian context around the beginning of the Settecento. As early as 1711, Veronese scholar Scipione Maffei suggested in a letter to the Duke of Savoy Vittorio Amedeo II, who was about to found a new university at Turin, that there be installed among the forty or so proposed cattedre at the new institution a chair in “Istoria Letteraria” for the express purpose of studying “i tanti monumenti e scritti de’ mezzani e barbari secoli” (‘the many monuments and writings of the middle and barbarous centuries’). Maffei justified this novelty with the sensible proposition that in the study of medieval history “stanno nascose le radici delle presenti cose” (‘are hidden the roots of our present environment’)8. According to Eric W. Cochrane, Italian letterati in the Seicento viewed the sixteenth century as having ushered in the first “end of history.” Maffei’s proposal represented one of the first steps in restoring this history:

210[H]istory, as a record of change through time, had stopped sometime between the fall of the Sforza, the sack of Rome, and the siege of Florence; they supposed, that is, that during the first half of the sixteenth century the undifferentiated succession of wars, battles, plagues, and feuds […] had given way to the unruffled tranquility of paternal despotism9.

At first, the expression mezzani e barbari secoli had descriptive rather than critical value. Medieval had yet to acquire the pejorative connotation of the “Dark Ages” or something that offends our modern sensibilities. It simply denoted the period in history before time stopped and the vertiginous back-and-forth of regime change was, at least according to seventeenth-century perspectives, halted for one-and-a-half centuries. After Maffei’s epistolary use of mezzani secoli in 1711, it appears that the term mezzi tempi first appeared in Italian, in print, towards the close of the eighteenth century in Girolamo Tiraboschi’s monumental Storia della letteratura italiana (1772-1782, 13 volumes)10. (Ludovico Muratori had published Antiquitates italicæ medii ævi [6 vols. fols., Milan, 1738-1742] three decades before using the Latin term medii ævi, but Tiraboschi’s is the first instance of the term in the vernacular).

The late appearance of the term makes perfect sense: in order to have a “Middle Age” wedged between the Classical period and the Renaissance, there had to be an age that came after, for it was only with the perspective of the early modern period and the exhaustion of the Renaissance that Italian men of letters conceived of a new period flanked by fruitful epochs of literary production. Tiraboschi’s 13-volume history of Italian literature set the standard and was the first systematic treatment of the subject. His effort, however, was not the first attempt to systematize literary production in Italy, whether in the Latin of the Classical period or in the Italian vernacular inaugurated at the court of Frederick II. Tiraboschi was preceded by Bembo’s Prose della volgar lingua, whose humanistic exposition and argument for the use of Trecento Florentine in 1525 came amidst a spate of books published from the cities of Florence and Venice whose topics dealt with Italian language11. Not even Bembo’s watershed publication, though, 211signaled the first treatment of Italian literary history. That distinction belongs instead to Dante Alighieri’s DVE and its attempts to trace the lineage of Italian vernacular poetry and situate it within a pan-European context that included Old Occitan and French, and even Hebrew, Latin, and Greek. Though Dante’s effort was far from comprehensive, Carlo Dionisotti first identified this antecedent when he commented that “la storia della letteratura italiana non comincia con le Prose di Bembo, comincia col De vulgari eloquentia di Dante12”. It is my contention that this connecting thread runs from Dante to the Seicento, and that Ménage’s annotations to the 1577 DVE confirm Dionisotti’s contention that the history of Italian literature begins, not with Bembo’s Prose, but with Dante’s Latin treatise.

Gilles Ménage and his annotations

to the 1577 De vulgari eloquentia

Let us begin at the end. What does Ménage’s interest in the DVE tell us about his view of the Middle Ages? There was no one better positioned to bridge the gap between the “Ancients” and the “Moderns,” or in this case the “Medieval” and the “Early Modern,” as we have come to call the periods in which Dante wrote and in which Ménage was active. As Richard G. Maber has argued, Ménage himself defied simplified labels: “the impossibility of categorizing Ménage too neatly is exemplified […] by his ambiguous position in the Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes,” in which he both “admired that great defender of the Anciens, Anne Dacier” and “appreciated ‘modern’ literature and was very friendly with Charles Perrault, the leading Moderne13”. That is, among 212the antiquarians – if such a label can accurately describe Ménage – it was he who represented the synthesis between contemporary research and the “hidden roots of the present environment”, to quote again Scipione Maffei’s 1711 letter to the Duke of Savoy. The Mannheim copy of the 1577 DVE, along with Ménage’s mentions of both the Latin treatise and Corbinelli in his Le origini della lingua italiana, testify to the consciousness of Dante’s role in the invention of Italian and Italian literature in the early modern period. Ménage’s historical studies peel back the seemingly undifferentiated mass of history covered by the expression mezzi tempi and allow us to talk about “Seicento Medievalists.”

How did Ménage happen upon the De vulgari eloquentia? Dante’s treatise would have been useful to Ménage as he was preparing his own Le origini della lingua italiana (1669). Indeed, throughout Le origini della lingua italiana Ménage cites both Corbinelli and Dante in the DVE as linguistic and poetic authorities, as in the case of Dante and the stanza:

Stanza. Sorta di Poësia, usata per lo più nelle Canzoni e ne’ Poemi Eroici. Dante Alighieri nel libro secondo della Volgare Eloquenza, là dove tratta della Stanza della Canzone.

(Le origini della lingua italiana, c. 452, 1685)14

If we turn to Ménage’s annotations in the 1577 DVE, we find the exact place where he noted Dante’s treatment of the stanza (interleaf after c. 51; see fig. 2). Ménage’s reliance on Dante—and Corbinelli—stems from geographical distance and the difficulties he encountered in acquiring Italian books, but also from the sommo poeta’s status as an authority, an authority that moved from vernacular Italian to vernacular French. In the preface to Le origini della lingua italiana, addressed to his friends the “Signori Accademici della Crusca,” Ménage writes of the impediments he faced in carrying out his studies of Italian: he did not have access to a large number of books in Italian; he was a foreigner; and he had never been to Italy:

e ’l non aver avuto quella quantità di libri Italiani, che bisognava per lavoro sì grande; e quel che più importa, l’essere io straniero nell’idioma in cui scrivo; nè anche mai stato nel bel paese ch’Apennin parte, e ’l Mar circonda e l’Alpe.

213Despite his protestations, Ménage’s scientific study and his acute sense of the relationship between Bembo’s Prose and Dante’s DVE bookend neatly the years spanning 1525-1700, a period of “paternal despotism” undifferentiated from the time of the sack of Rome and the siege of Florence (1527) until the start of the eighteenth century. Early moderns viewed 1527 as the unofficial end of the period that in the Settecento would be newly coined as mezzi tempi. Ménage’s annotations testify to a precocious reception of medieval Italian literature and language, as well as to the success of the rhetorical and conceptual categories in the DVE that aided in molding the paradigms of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century reception of medieval Italian poetry and supported the questione della lingua in both Italy and France.

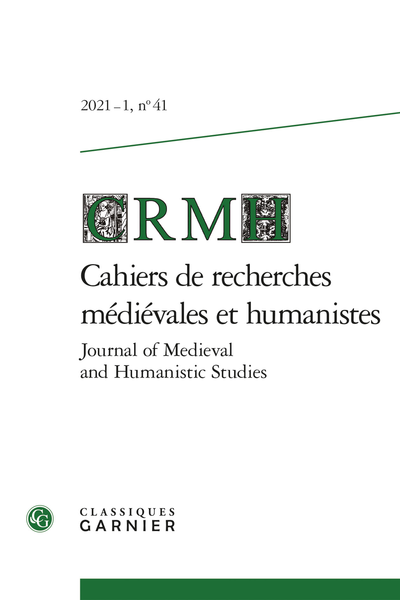

To read Ménage’s copy of the DVE is to anticipate the “return of history” in the Settecento, a return evidenced by his understanding of the DVE’s role in Bembo’s Prose della volgar lingua and in the study of Italian language(s). Ménage’s keen attention to the medieval roots of Bembo’s Renaissance study of the Italian language went against the dominant current of a century characterized by a “belief in the immutability of the present [that] rendered futile any attempt to place it in perspective between past and future and discouraged, therefore, any investigation of its historical origins15.” In Ménage’s work, the emphasis on the continuity between the Middle Ages and the present age distinguished him from “the philosophes beyond the Alps [who] were decrying the remnants of the past as an impediment to the spread of Enlightenment in their own times16.” Revolting against this anti-historical atmosphere, Ménage’s contribution also takes up the contemporary Accademia della Arcadia’s call to “resuscitate the creative power of the Trecento Masters17”. In Dante’s medieval treatise, Ménage found the roots of contemporary Italian. To see how this is true, let us turn to Ménage’s notes and the 1577 DVE. The French Italianist’s annotations vis-à-vis Dante and Bembo fall under three categories: (1) observations related to poetics; (2) a simple note that Bembo, too, cited a given poem or an author mentioned by Dante; and (3) a direct comparison between Bembo’s Prose and Dante. For example, in over a dozen instances Ménage notes the apriority of Dante’s De vulgari 214eloquentia with respect to Bembo’s Prose della volgar lingua: “Bembo calls him Geraldo Brunello”; “Bembo, too, makes mention of Rinaldo d’Acquino” (from the Mannheim copy of Jacopo Corbinelli’s 1577 De vulgari eloquentia, c. 43v) and: “Gottus Mantuanus - Bembo, Book Two of his Prose he says that he [Gotto] had Dante as a listener of his canzoni and he cites in his Prose and others that are in this [DVE] and [that] are not” (see fig. 1). Ménage’s annotations mentioning Bembo’s Prose are focused on individual poets named by both Dante and Bembo, as well as on questions of poetics. For instance, Ménage discusses Dante’s treatment of the hendecasyllable, the Italian poetic meter per eccellenza discussed at length by Bembo (see fig. 2). Many other annotations are laconic and mention simply where in Bembo’s Prose one can find the poet named by Dante. In his interest in the Italian Middle Ages, Ménage anticipated Italian letterati Muratori and Tiraboschi. Indeed, Ménage’s appreciation means that we should consider him among the “colleagues in France and Germany [whose] works were known, their methods imitated, and their friendship treasured18.” Ménage, like his successors in the Settecento, “shook the prevailing confidence in the immutability of the present and stimulated a consciousness of development through time, […] drawing attention to […] the intimate connection of past and future19.” Ménage’s annotations to the DVE connect the present with the past by recognizing that Bembo’s categorizations have their origins in Dante’s medieval treatise and that this paradigm connects past, present, and future. The international character of Ménage’s scholarship and his participation in the early modern Republic of Letters prove that the “return of history” needs to be dated much earlier. His scholarship illuminated the relationship between the Middle Ages and the present.

The Giuntina di rime antiche’s paratext

and its twin premises

One of the most vociferous Petrarchan partisans among Italian letterati was, of course, Pietro Bembo, editor, philologist, poet, who had 215long championed Petrarca’s Latinate style as the ideal technical form for writing poetry, most prominently in his Prose della volgar lingua. What’s more, even early-printed books that seem to have nothing to do with Petrarca, like the one published by the Giunti in Florence just two years after Bembo’s Prose, in 1527, and entitled Sonetti et canzoni di Diversi Antichi Autori Toscani in dieci libri raccolte, are in reality under his shadow. This book, for example, though superficially anti-Petrarchan in agitating for going beyond Petrarca as the model for poetry and promoting a gratitudine towards older poets that recalls Boccaccio’s own emphasis on the virtue in the prologue to the Decameron, not coincidentally a work published by the same Giunti press in that same 1527, takes its title “Sonetti et canzoni” from a spate of books publishing Petrarca’s Rerum vulgarium fragmenta, popularly known as the Canzoniere, in a similar fashion, as “Petrarch’s sonetti and canzoni20.”

The paratext of the 1527 Giuntina advances a bipartite understanding of Italian medieval literature. First, it is “archeological,” that is, medieval literature is analogized to Hellenestic and classical Roman statuary recently recovered in Rome, and that features a patina of grime, of historical detritus. Even the title’s “Antichi Autori Toscani” (my emphasis) indicates the distance between the sixteenth century and the poetry anthologized. Towards the close of the dedicatory letter, the editor Bardo Segni alludes to the real purpose for studying Duecento poets like Guittone, and compares his efforts at gathering together the “old poems of the Tuscan poets” to the archeological recovery and restoration of ancient Roman statues. It is in the preface that one grasps the splendidly archaeological and antiquarian influence on the 1527 Giuntina:

E con quella più diligenza e cura, che per me si poteva ricercando gli antichi scritti de Toscani auttori, non altrimenti che fra le eccelse rovine della infelice Roma poco innanzi a queste sue così crudeli ed estreme calamitati le molto artificiose statue de gli antichi maestri—dalla ingiuria e violenza de tempi in molte parti spezzate e sparse—fino dal profondo ed ultimo seno della oscura terra dalla diligenza e sollecitudine di qualcuno insieme raccolte e da ogni bruttura e macchia ripulite.

“And with the greatest diligence and care that I could muster, [I was] studying the ancient writings of the Tuscan poets, no differently than the many elaborate statues of the ancient masters found among the ruins of unfortunate 216Rome shortly before such cruel and extreme calamities befell her. These statues were broken into many pieces and scattered due to the damage and violence of the times, and gathered together from the very depths of the dark earth, thanks to the diligence and concern of some, and purged of every ugly mark and stain.”

The second feature of the Giuntina’s paratext is its emphasis on the progressive nature of the invention of Italian vernacular poetry, and on the coarse, rough, and inchoate nature of early Italian poetry. In the construction of a consciously medieval poetry in the Giuntina (again the “Antichi Autori Toscani”), Segni, the poet-editor of the 1527 Giuntina, operated on two contrasting principles. He simultaneously characterized pre-Dantean and pre-Petrarchan poetry as “worthy of gratitude”, (continuity) yet admitted that it was “coarse and rough”, (rupture) both explicitly in the preface and implicitly by Petrarchizing Guittone d’Arezzo’s poetry21:

Che se ciò bene è vero, che il Petrarca molto più che ciascuno altro toscano autore lucido e terso sia da giudicare, nondimeno, né qual de duoi vi vogliate, o Cino o Guido, degni saranno già mai di dispregio tenuti. Né il divino Dante ne le sue amorose canzoni indegno fia in parte alcuna riputato di essere insieme con il Petrarca per l’uno de’ duoi lucidissimi occhi de la nostra lingua annoverato. (c. 2r)

“If that is true, that Petrarch is to be judged as more polished and clear than any other Tuscan poet, nevertheless, choose either of the two, Cino [da Pistoia] or Guido [Cavalcanti], neither is worthy of being held in contempt. Nor are the divine Dante and his canzoni on love judged to be unworthy in any respect of being grouped together with Petrarch as one of the two most-polished leading lights of our language.”

Meant to extol the pre-Petrarchan lyric tradition, especially that which is Dantean, the Giuntina is heavily indebted both to Petrarchan lyric and the sixteenth-century printing industry. It uses sixteenth-century antiquarian language to describe the contents of the volume, but it also uses a schematization and language that are indebted to Dante of the DVE. It depicts the Italian tradition as one of continuity, yet emphasizes the rupture present between the early vernacular poets and Dante22. The 217Giuntina’s acceptance of Dantean norms is explicit: the very opening of the premise indicates that the reason for the volume, or at least the reason for its leitmotif – a progressive view of Italian poetry led by Dante – was occasioned precisely by a desire to counter the dominance of Petrarca as the poetic model in Italy and in Europe tout court.

The Giuntina di rime antiche

and De vulgari eloquentia

We have seen that the Giuntina di rime antiche interpreted medieval poetry as “classical statuary,” artifacts to be polished in “un’operazione di recupero archeologico23.” Its preface and its appreciation of the pre-Dantean lyric tradition exists because the endpoint of that tradition is Dante himself. As Enrico Stoppelli has noted recently, the raison d’etre of the Giuntina was to “rivendicare […] il ruolo fondativo di Dante e della tradizione toscana anche nell’ambito del genere lirico24.” (Something Ménage’s annotations do as well.) The juxtaposition of vernacular Italian’s earliest poets and Dante’s lyric was also present in an earlier collection, the so-called Raccolta aragonese, compiled for Lorenzo il Magnifico and featuring a preface by Poliziano (1472). So this dichotomy is not new. However, the antiquarian rhetorical categories used by Poliziano in the 1472 Raccolta Aragonese, by Bembo in 1525 and by the Giuntina in 1527, all embrace Dante’s language to describe the progression of Italian lyric. For example, let us look at Bembo’s contention that the language of pre-Petrarchan and pre-Dantean poets was rough and coarse:

Era il nostro parlare negli antichi tempi rozzo, e grosso, e materiale; e molto più olivo di Contado, che di Città. Per la qual cosa Guido Cavalcanti, Farinata degli Uberti, Guittone, e molti altri, le parole del loro secolo usando, lasciarono le rime loro piene di materiali e grosse voci altresì […]”. (Prose I XVII, italics mine).

218“Our speech in ancient times was rough, coarse, and base, and so much more at home in the country than in the city. Because of this Guido Cavalcanti, Farinata degli Uberti, Guittone, and many others, using words from their time, left their poems full of base and coarse words. Nor were they cured of this, for their Italian language bequeathed us in large measure the first, tough layer of bark on its trunk.”

As for the Giuntina, not only are pre-Petrarchan poets – especially Dante – to be shown appreciation, they also form part of a continuous history of vernacular lyric that is progressive. Of note here is that recurring term rozzo, this time used adverbially to describe the earliest vernacular poets:

Che così come nessuna cosa primieramente trovata in un medesimo tempo alla sua perfettione potette aggiugnere giamai, anzi per molte età da diversi ingegni maneggiata, aggiugnendo ogni giorno qual che cosa di nuovo alle trovate finalmente all’ultimo suo grado salita si posa. Così a poco a poco, questo vostre modo di scrivere toscano rozzamente dai primi trovato per molte mani tutta fiata più gentile e più leggiadro scegliendo sempre i moderni quello che i loro passati di ornato e’ bello hausano. (Giuntina di rime antiche)

“Just as you are unable to reach the height of perfection of a thing in that same moment, rather it is developed over many ages and by many different talents, every day something new is added to what has come before it so that one day, finally, that thing reaches its apex. So that, little by little, this way of yours of writing Tuscan, begun coarsely by the first poets, becomes more smooth and elegant with each successive hand, with contemporary poets always choosing the beautiful and ornamented words used by those poets who came before.”

The germ of this conception of medieval poetry has its beginnings in Dante. In DVE I 13, Dante makes a similar comparison between provincial and municipal poets:

Et in hoc non solum plebeia dementat intentio, sed famosos quamplures viros hoc tenuisse comperimus: puta Guittonem Aretinum, qui nunquam se ad curiale vulgare direxit, Bonagiuntam Lucensem, Gallum Pisanum, Minum Mocatum Senensem, Brunectum Florentinum, quorum dicta, si rimari vacaverit, non curialia sed municipalia tantum invenientur. (Dante, DVE, I 13 1; my italics)

“And it is not only the common people who lose their heads in this fashion, for we find that a number of famous men have believed as much: like Guittone d’Arezzo, who never even aimed at a vernacular worthy of the court, or Bonagiunta da Lucca, or Gallo of Pisa, or Mino Mocato of Siena, or Brunetto the Florentine, all of whose poetry, if there were space to study it closely here, we would find to be fitted not for a court but at best for a city council.”

219According to Stoppelli, the list of poets in Lorenzo il Magnifico’s/Poliziano’s 1472 Raccolta aragonese and in Bembo’s Prose suggested to the curators of the Giuntina di rime antiche the poets to include in their own volume. However, it is important to point out that the poets in all three of these works – the 1472 Raccolta, the 1525 Prose, and the Giuntina – are Dante’s poets in the DVE. Bembo’s enumeration of the “eccellenti scrittori […] e nel verso e nella prosa” illustrates Dante’s legacy:

messer Guido Guiniccelli Bolognese anch’egli, molto da Dante lodato, Lupo degli Uberti, che assai dolce dicitor fu per quella età senza fallo alcuno, Guido Orlandi, Guido Cavalcanti, de’ quali tutti si leggono ora componimenti; e Guido Ghislieri e Fabruzio bolognesi e Gallo pisano e Gotto mantavano, che ebbe Dante ascoltatore delle sue canzone, e Nino Sanese e degli altri, de’ quali non cosi’ ora componimenti, che io sappia, si leggono. (II II, italics mine)

“Messer Guido Guinizzelli, also Bolognese and very much praised by Dante, Lupo degli Uberti, who was without flaws and was a rather smooth vernacular poet for his age, Guido Orlandi, Guido Cavalcanti, whose poetry everyone still reads today; and Guido Ghislieri and Fabruzio Bolognesi and Gallo Pisano and Gotto Mantovano, who counted Dante among the listeners of his poems, and Nino Sanese and others, whose poetry, at least that I am aware of, is no longer read today.”

The index of poets in the Giuntina di rime antiche bears a strong resemblance to this passage in Bembo’s Prose: Dante Alighieri (Books I-IV); Cino da Pistoia (Book V); Guido Cavalcanti (Book VI); Guittone d’Arezzo (Book VIII); pre-Dantean poets (Book IX). Still other poets mentioned by Bembo – Guido Ghislieri and Fabruzio Bolognese – are singled out by Dante elsewhere in the DVE.

Just how formative was the DVE in shaping the sixteenth-century reception of medieval Italian literature? We have already seen that the structure and the poets anthologized in the Giuntina di rime antiche, along with the language of the paratext, took their cues from Dante. The strength of the DVE, filtered through the success of Bembo’s own Prose della volgar lingua, emerges in Corbinelli’s 1577 edition of the DVE and in the notes of French Italianist Ménage. Corbinelli’s description of Dante’s predecessor Guittone d’Arezzo as rozzo echoes the language used in the Giuntina di rime antiche, the Raccolta Aragonese, and especially the DVE. Corbinelli writes that:

220[D]iremo, che Guittone, scrittore così sano, & sincero, & più sempre dedito alla sententia ch’a la parola, si possa a Polignoto non senza causa comparare, il quale come nascente, rozzo principio fu di quella Arte, che poscia divenuta adulta & matura.

“We will say that Guittone, such a fine and sincere writer, always more dedicated to the sententia [maxim, saying] than to the word, can be compared with good reason to [the Greek vase-painter] Polygnotos, who was the rough, coarse beginner of that art that then became mature and adult.”

Like Corbinelli, Ménage gives credence to Dante’s categorizations. His notes are filled with references to classical authors, but the author and work cited most often by Ménage are Bembo and his Prose della volgar lingua. The frequency of interleaf manuscript notations from the 1577 DVE and that remand the reader to Bembo’s Prose della volgar lingua demonstrate the extent to which all of medieval Italian lyric was shaped by Dante’s judgments, hierarchies, and asides through the conduit of Bembo’s Prose. Dante’s systematization of literary culture is evidenced by Ménage’s notes in the Mannheim copy. Bembo’s Prose had an outsized influence on the physiognomy of medieval Italian vernacular lyric in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and Ménage, as a full participant in the early modern European Republic of Letters, understood Dante’s influence on Bembo’s Prose and modern thought. Though Dante was not an “Ancien”, he was a member in good standing of the mezzi tempi, and Ménage shows that early modern Italian was not so much a rupture with the medieval period, but its linguistic and cultural heir. Ménage, the Giunti brothers (with editor Bardo Segni), and even Jacopo Corbinelli, accept Dante’s judgments of medieval Italian poets.

Conclusion

The Giuntina di rime antiche’s paratext, Bembo’s Prose and, fifty years later, the editio princeps of the DVE, and nearly one-hundred years after that, Ménage’s notes, testify to the ways in which Dante’s treatise shapes our view of medieval Italian lyric and illustrate the Seicento’s reliance on the literary and cultural categories advanced three centuries before in the DVE. Dante’s role in the Seicento study of Italian 221language and lyric is all the more remarkable for a century was coined “il secolo senza Dante25”. In the case of the Giuntina di rime antiche and its adherence to Dantean categories, the influence is particular strong, as the Giuntina would remain the anthology of medieval Italian lyric on up until the Ottocento. On the other hand, Bembo’s familiarity with the DVE comes through in the dichotomies of medieval language he outlines and even in the poets he enumerates. A now-lost iteration of Bembo’s Prose, at least the first two books, had been composed and sent to some Venetian friends already in 1512. It is clear that Bembo, upon meeting Trissino in Rome in 1514 and having himself made a copy of the Trivulziano MS of the DVE (Vat. Lat. Reg 370), re-elaborated the first two books of the Prose on the basis of Dante’s Latin treatise. While it is certain that in Italian the term “medieval” was coined only in the eighteenth century, Dante himself was already aware, as early as 1303, that there was something particular about the pre-Dantean Italian lyric tradition. It is to Dante that one can trace many of the archaeological terms used to describe medieval Italian poetry in the 1527 Giuntina di rime antiche, as well as the categorizations exploited by Bembo in his landmark Prose della volgar lingua, an inheritance duly noted by Ménage in his annotations to the 1577 DVE. The invention of medieval Italian literature, though it received a new impetus in the sixteenth century, can be located much earlier. The return of history and its healthy respect for the Middle Ages can be anticipated to at least the second half of the Seicento, when Ménage’s studies of the 1577 DVE identify the medieval Latin treatise as a critical source for Bembo’s study of lyric and language. The synthetic figure of Gilles Ménage testifies to the continuity of thought between the composition of medieval Italian poetry and its invention in the Settecento.

Anthony Nussmeier

University of Dallas

222

Fig. 1 – Annotations in the hand of Gilles Ménage: “Gottus Mantuanus - Bembo, Book Two of his Prose he says that he [Gotto] had Dante as a listener of his canzoni and he cites in his Prose and others that are in this [DVE] and [that]

are not.” This is one of dozens of annotations in which Ménage

identifies a coincidence between Bembo’s Prose and Dante’s DVE

(Mannheim copy, 1577 editio princeps of De vulgari eloquentia).

Fig. 2 – Annotations in the hand of Gilles Ménage, noting where Bembo discusses the “endecasillabum” that Dante takes up in the DVE.

This is one of dozens of annotations in which Ménage identifies

a coincidence between Bembo’s Prose and Dante’s DVE

(c. 42, Mannheim copy, 1577 editio princeps of De vulgari eloquentia).

1 First composed between c. 1300/1304-1305, the De vulgari eloquentia was not published in any form until Giangiorgio Trissino’s translation into Italian in 1529; J. Corbinelli, DANTIS ALIGERII precellentissimi poetae de vulgari eloquentia libri duo nunc primum ad vetusti et unici scripti codicis exemplar editi ex libris Corbinelli eiusdemque adnotationibus illustrati. Ad Henricum Franciae Poloniaque regem christianissimum, Parisiis, I. Corbon, 1577.

2 French Jesuit F.-J. Terrasse Desbillons (1711-1789) was the last individual owner of the volume. The Mannheim copy once owned by Ménage can be accessed at here: http://www.uni-mannheim.de/mateo/itali/autoren/dante_itali.html [retrieved 15/01/2021].

3 R. G. Maber, ed., Publishing in the Republic of Letters: The Ménage, Grævius, Wetstein Correspondence 1679-1692, Amsterdam and New York, Rodopi, p. 7.

4 For more on the De vulgari eloquentia’s role in the French question de la langue, see M. Lucarelli, “Il ‘De vulgari eloquentia’ nel Cinquecento italiano e francese”, Studi francesi, 59, 2015, p. 247-259.

5 See E. Pistolesi, “Con Dante attraverso il Cinquecento: il De vulgari eloquentia e la questione della lingua”, Rinascimento, 40, 2000, p. 269-296.

6 MS Vat. Lat. Reg 370. See A. Sorella, “La norma di Bembo e l’autorità di Petrarca”, Il petrarchismo. Un modello di poesia per l’Europa, vol. 2, ed. F. Calitti and R. Gigliucci, Roma, Bulzoni, 2006, p. 1-18.

7 See the introduction of D. De Robertis ed., Sonetti e canzoni di diversi antichi autori toscani, 2 vols, Firenze, Le Lettere, 1977.

8 Cited from E. W. Cochran, “The Settecento Medievalists”, Journal of the History of Ideas, 19/1, 1958, p. 35-61, at p. 35. Maffei’s citation can be found in Maffei Scipione, Parere sul migliore ordinamento della R. Università di Torino (op. post.: Verona, 1871), p. 7.

9 Cochrane, “The Settecento Medievalists”, p. 37.

10 Girolamo Tiraboschi, Storia della letteratura italiana, Modena, 1787, 13 vols.

11 Among them the 1527 anthology of pre-Petrarchan medieval poetry Sonetti et canzoni di Diversi Antichi Autori Toscani in Dieci libri raccolte; Giangiorgio Trissino’s vernacular translation of Dante’s De vulgari eloquentia (1529) and his Epistola de le lettere nuovamente aggiunte de la lingua italiana (1524); Martelli’s Risposta alla epistola delle nuove lettere nuovamente aggiunte alla lingua volgare fiorentina (1524); Firenzuola’s Discacciamento delle nuove lettere (1524); and Machiavelli’s Discorso intorno alla nostra lingua. Not to mention Giovan Francesco Fortunio’s Regole grammaticali della volgar lingua (1516).

12 C. Dionisotti ed., Pietro Bembo, Prose della volgar lingua, Torino, UTET, [1960] 2nd edition 1966, p. 42.

13 R. G. Maber ed., Publishing in the Republic of Letters: The Ménage, Grævius, Wetstein Correspondence 1679-1692, Amsterdam and New York, Rodopi, 2005, p. 7.

14 “The stanza. A type of Poetry, used for the most part in canzoni and in Epic Poems. Dante Alighieri in the Second Book of the De vulgari eloquentia there were he treats of the stanza of the canzone.” In fact, in the Mannheim copy of the De vulgari eloquentia we have Ménage’s notes on this section of the DVE (c. 51).

15 Cochrane, “The Settecento Medievalists”, p. 37.

16 Cochrane, “The Settecento Medievalists”, p. 36.

17 Cochrane, “The Settecento Medievalists”, p. 38.

18 Cochrane, “The Settecento Medievalists”, p. 53.

19 Cochrane, “The Settecento Medievalists”, p. 61.

20 See A. Nussmeier, “‘Madre’ e ‘padre del cielo’: Petrarca in Guittone della Giuntina di rime antiche”, Medioevo letterario d’Italia, 9, 2012, p. 89-103.

21 Ibid.

22 Corrado Bologna also notes that this is a bit of Florentine revenge for Venice’s preeminence in the field, especially vis-a-vis Petrarch, of whom there appear 27 Venetian editions and only 3 Florentine editions between 1515-1527. C. Bologna, Traduzione testuale e fortuna dei classici, in Letteratura italiana, dir. A. Asor Rosa, VI. Teatro, musica, tradizione dei classici, Torino, Einaudi, 1986, p. 445-928, at p. 604.

23 E. Stoppelli, “La Giuntina di Rime Antiche”, Antologie d’autore: la tradizione dei florilegi nella letteratura italiana, ed. by E. Malato and A. Mazzucchi, Roma, Salerno, 2016, p. 158-172, at p. 164.

24 Stoppelli, “La Giuntina di Rime Antiche”, p. 159.

25 But see M. Arnaudo, Dante barocco. L’influenza della Divina Commedia su letteratura e cultura del Seicento italiano, Longo, Ravenna, 2013, for a revisionist study of the so-called “secolo senza Dante.”