Reappraisal of a literary topos, the medieval found manuscript The case of Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon and the Gallaup de Chasteuil brothers

- Type de publication : Article de revue

- Revue : Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes - Journal of Medieval and Humanistic Studies

2021 – 1, n° 41. varia - Auteur : Douchet (Sébastien)

- Résumé : Du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle, la famille Gallaup de Chasteuil a constitué à Aix-en-Provence une bibliothèque privée rassemblant un nombre considérable de manuscrits et d’imprimés médiévaux, qu’ils ont lus, annotés et recomposés. L’étude de cette bibliothèque et de certains de ses exemplaires conservés, qui n’avaient jamais été identifiés comme tels jusqu’à présent, est extrêmement précieuse pour comprendre une réception et une lecture des textes médiévaux sous l’Ancien Régime.

- Pages : 319 à 343

- Revue : Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes - Journal of Medieval and Humanistic Studies

- Thème CLIL : 4027 -- SCIENCES HUMAINES ET SOCIALES, LETTRES -- Lettres et Sciences du langage -- Lettres -- Etudes littéraires générales et thématiques

- EAN : 9782406119968

- ISBN : 978-2-406-11996-8

- ISSN : 2273-0893

- DOI : 10.48611/isbn.978-2-406-11996-8.p.0319

- Éditeur : Classiques Garnier

- Mise en ligne : 07/07/2021

- Périodicité : Semestrielle

- Langue : Anglais

- Mots-clés : lectorat, juristes, Provence, manuscrits, imprimés

Reappraisal of a literary topos,

the medieval found manuscript

The case of Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon

and the Gallaup de Chasteuil brothers

The turn of the 17th and 18th centuries marks the “rediscovery of the troubadours” amongst the Parisian intellectual and social circles1. The “gallant troubadours2” and their poems are in favour in conversations and debates, but also correspondences, gazette articles, as well as scientific and fictional works. They are seen as pioneering ancestors of gallantry — a modern, aristocratic, and feminine movement. In 1702, in her Apothéose de Mademoiselle de Scudéry (Apotheosis of Mademoiselle de Scudéry), Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon places the troubadours in the parade of poets celebrating Scudéry’s apotheosis, in other words the writer’s arrival on the Parnassus:

Tibule & Properce y paroissoient des premiers couronnez de Lauriers brillans & de Mirthes fleuris. On remarquoit dans cette troupe avec plaisir les galans Troubadours de Provence. Ceux qui paroissoient avec le plus de distinction parmi ces Poëtes étoient, Jaufred de Rudel, mort d’amour pour une princesse étrangere qu’il avoit été chercher au travers des mers sur le seul récit de ses charmes; Guilhem Adhemar, mort de la même passion que Jaufred pour la belle et sçavante Comtesse de Die. Elyas de Barjols, 320Chevalier, Chevalier de la belle Princesse de Forcalquier, & Boniface de Castellane, amant passionné de la charmante Belliere. Le souvenir des délicates amours & des beaux ouvrages de ces Poëtes, les faisoit regarder d’abord avec attention3.

“Tibullus and Propertius are amongst the first, crowned with shiny laurels and blooming myrtle. Agreeably, the gallant troubadours of Provence were part of the cortège. Those who appeared with most distinction amongst the Poets were Jaufred de Rudel, who died from his love for a foreign princess for whom he sailed across the sea after learning about her charms; Guilhem Adhemar, who died from the same passion as Jaufred for the fair and wise Comtesse de Die. Ellis de Barjols, Knight, lover of the fair Princess of Forcalquier, and Boniface de Castellane, passionate lover of the comely Belliere. The remembrance of the Poets’ delicate loves and beautiful works drew much attention to them at first.”

In the description of the procession, Jaufré Rudel, Guilhem Adhemar, Elyas de Barjols, Boniface de Castellane follow the likes of Tibullus and Propertius in a cortège that also includes 14th to 17th century poets (Petrarch, Marot, Honoré d’Urfé, Marin Le Roy de Gomberville, Jean Desmarets de Saint-Sorlin, etc.). This description poetically mimics the movement of Literary History conceived as an uninterrupted continuum.

More specifically, in the gallant circles, the legend of medieval love courts has been abundantly commented upon: the active participation of women in poetic creation and their function as secular judges in matters of love morality in the courts seem to have heralded and justified the active role of women and their salons in the establishment of civility and amiability — two core characteristics of gallantry. The revival of troubadours at the end of the 17th century is another aspect of the long-running quarrel between the Ancients and the Moderns, and became a means of finding a non Graeco-Latin origin for French literature, at the price of being far-fetched, especially in assimilating Provençal to French and inventing a genealogy that would poetically and historically link the troubadours to the gallant milieux of the late 17th century. It is known that the integration of medieval historic and literary material in current debates triggered numerous aesthetic and 321ideological quarrels4. Moreover, when high society gallants claim a filiation with the “Gaulish Antiquity5” as a novel source of knowledge and creation, the link is in reality very tenuous.

Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon, in her Lettre à Melle D. G** (Letter to Melle D. G**), describes that very link in a visibly contradictory fashion. Through the organic, irresistible movement of History, the form of the novel, described as the troubadours’ invention, lived on and perfected until Mademoiselle de Scudéry:

Ces galans troubadours virent beaucoup enrichir sur leurs projets. Avant eux, on n’avait point entendu parler de Romans: on en fit: de siecle en siecle ces sortes de productions s’embellirent, & elles sont venuës enfin à ce comble de perfection où l’illustre Mademoiselle de Scudéry les a porté6.

“The gallant troubadours pre-empted that their works would be developed upon. Before them, novels were unknown. Then some were written. For centuries, this type of production became increasingly beautiful, and they finally reached the perfection up to which Mademoiselle de Scudéry raised them.”

However, this continuous embellishment of the novel genre is not simply linear, and Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier dwells on the reasons why: the troubadours’ tales were transmitted orally to children through governesses and grandmothers “in order to shape their minds with a hatred for vice and a love for virtue” (“pour leur mettre dans l’esprit la haîne du vice & l’amour de la vertu”). Through the centuries, the novels have “degenerated” and “lost part of their beauty” (“dégénéré” and “perdu 322de leur beauté”). But they would later come back into fashion thanks to their simplicity and the purity of the mores they advocate for.

Cette décadence des romans en ayant fait prendre du dégoût, on s’est avisé de remonter à leur source, et l’on a remis en regne les Contes du stile des Troubadours7.

“The decadence of these novels caused their waning favour, it thus seemed wise to trace them back to their sources, which triggered the revival of the troubadour tale.”

It is easy for the reader to assume that Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier rhetorically hides behind the convenient indefinite phrasing of “it seemed wise” (an impersonal “on” in French). She presents herself as one of the pioneers of that return to the sources. She states that she read two genuine medieval manuscripts (i.e. not corrupted second-hand modern editions) in order to write her tale collection entitled La Tour ténébreuse ou les jours lumineux (The Dark Tower and the Bright Days) in 1706. However, scholars like Marine Roussillon consider the troubadour sources of the gallant milieux predominantly secondary printed sources, essentially Jean and César de Notredame, and Étienne Pasquier. Alicia Montoya also shares this opinion8. According to such studies, the access to medieval manuscripts appears to be marginal9.

Is the found manuscript topos or reality? Until today, the topic has been rarely touched upon, or altogether ignored, following the argument that it had to be a fictional device invented by modern writers. However, in 1905, as an overlooked footnote in the Romania review, Alfred Jeanroy introduces an element of doubt that I will dissipate. Working on 17th century book collections brings some evidence. As an example, I will focus on the Gallaup de Chasteuil library. Pierre, the 323last living member of the family, attended Mademoiselle de Scudéry’s salon and Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier regularly. I was able to reconstruct the most part of the collection, owned by the family of parliamentary lawyers from Aix, with the help of two catalogues, one of which had been compiled by Hubert, Pierre’s brother10. The fund is considerable for the time (roughly 1800 volumes11) and comprises numerous medieval manuscripts and printed book (approximately 4-5% in 1672, 7% in 1705). I traced and identified some that proved particularly interesting in the sense that they shed light on their reception in the 17th century, through the limited but enlightening example of the learned parliamentary provincial nobility.

More specifically, in the 1670s, Hubert Gallaup de Chasteuil (born 1626, dead 1679) copied, annotated, pasted, cut, decomposed and recomposed some of his manuscripts, and he reconfigured them in collections of his own creation, most of which are kept at the Inguimbertine Library in Carpentras. Such striking material manipulations give the texts they contain a new contextual meaning. My aim is thus to evaluate an example of the reception of ancient texts in the 17th century through the study of some manuscripts in his possession, and to trace the method Hubert used to reconstruct and showcase a certain sense of connection between himself, the Middle Ages and medieval texts.

In her preface to the Tour ténébreuse, Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier states that she consulted two manuscripts from which she draws part of the raw material that she was to develop in her own work, as well as the three troubadour lyrics that she would cite. She gives details about the first manuscript, that would have been completed in 1308 by a so-called 324Jehan de Sorels, and supposedly comprised the life story of Richard the Lionheart, and also some of his works, “some tales and short gallant stories, all named Fabliaux”:

Un sçavant homme qui a une curiosité sans bornes pour tout ce qui regarde l’Antiquité Gauloise, avoit en sa possession le manuscrit dont je viens de parler, & voulut bien me faire part de ce rare Ouvrage, qu’on ne trouve qu’avec difficulté. C’est de ce Manuscrit que j’ay tiré les Contes du Roy Richard que je donne aujourd’huy au Public12.

“A learned man with an insatiable curiosity for anything related to Gaulish Antiquity had in his possession the manuscript that I just mentioned. He agreed to share the very rare document with me. It is from that manuscript that I drew the Tales of King Richard that I am giving to the public today.”

In order to authentificate the events disclosed in the manuscript, she admits that she cross-checked the facts with another manuscript.

& j’ay lû aussi un Manuscrit fort ancien d’un Auteur Anonyme, qui se trouve trés-conforme dans les faits qu’il rapporte du Roy Richard avec ce qu’en a écrit ce Roy luy-même dans le Manuscrit de Jean Sorels.

“And I read a very ancient manuscript by an Anonymous Author, which matches the account given on King Richard in the first Manuscript by Jehan de Sorels.”

The return to medieval sources enables the affirmation of a gallant feminine ethos which integrates erudition as one of its core values and saps the tales so “atrociously disfigured” (“défigurez impitoyablement”) by the governesses, as well as the poor copies and the chapbooks.

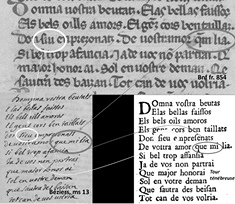

In a footnote from the Romania in 190513, Alfred Jeanroy indicates that Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier really did consult an authentic medieval songbook (BnF, français 854). There she appears to have found the stanza from a lyric by troubadour Blacatz, which she publishes in the preface to the Tour ténébreuse, and attributes to Blondel de Nesle and Richard Lionheart:

Chanson en Langue Provençale, dont

le commencement est de Blondel,

325& la fin du Roy Richard.

Domna vostre beutas

Elas bellas faissos

Els bels oils amoros

Els gens cors ben taillats

Don sieu empresenats

De vostra amor que mi lia.

Si bel trop affansia

Ja de vos non partrai

Que Major honorai

Sol en votre deman

Que fautra des beisan

Tot can de vos volria14.

The source manuscript is supposedly BnF, fr. 85415. However, things turn out to be more complex than they first appear to be. In a 1703 letter, Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier lengthily presents the medieval love courts to a noblewoman from Madrid. She praises the “Provençal gentleman full of profound knowledge” (“Gentilhomme de Provence plein d’un profond sçavoir16”), “Monsieur de Chasteüil17”, author of a Discourse in which she found what she knows about the love courts. Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier read the Discours des arcs triomphaux (Discourse of the Triumphal Arches), which was published two years before, in 1701, by Pierre Gallaup de Chasteuil18 who learned about the existence of those love courts through the copy of a medieval manuscript, a copy commissioned by his brother, Hubert:

326Et ce n’est que la lecture d’un Manuscrit, qu’Hubert de Gallaup Avocat general en ce Parlement mon frere, fit transcrire sur celuy qui est dans la Bibliotheque du Louvre, contenant la vie & les mœurs de nos Troubadours Provençaux, que je découvre l’origine et l’établissement de ce Parlement d’Amour, qui est le sujet que j’expose dans cet Arc19.

“And it’s only upon reading the manuscript — describing the life and mores of our Provençal troubadours — copied in the Louvre Library for my brother Hubert de Gallaup, Crown prosecutor at the parliament, that I found the origin and foundation of this Love Parliament, which is the theme that I expose in this Arch.”

L’Héritier quotes Pierre Gallaup who in turn quotes Hubert Gallaup, who owned the copy of a genuine manuscript. The start of this long citational chain is the copy of a largely unidentifiable manuscript. Such a blurring of sources confronts the reader to potential literary forgery.

However, the copy was found. It is a collection kept today in Béziers, and it begins with the words: “Aqui son escrih las Tensos qu’an trobadas los troubadors de Proensa20” (“Here are written the Tensos composed by the Provençal troubadours”). Geneviève Brunel-Lobrichon proved that the volume comprises the text of the 13th century Venetian-Paduan songbook referred to as “I21”. I add something that escaped Geneviève Brunel-Lobrichon — the fact that most of the handwritten copying was made by Hubert Gallaup himself22.

327Interestingly, the songbook referred to as “I” by Lobrichon and the one used by Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier according to Alfred Jeanroy23 (BnF fr. 854) are the same manuscript as it is well known in the Occitan Studies. I consulted the Béziers copy to check the authenticity of the cobla that L’Héritier reproduces in the Tour ténébreuse. And my suspicion was confirmed: L’Héritier doesn’t follow the text of Manuscript 854, as Jeanroy mistakenly stated it. She follows the copy handwritten by Gallaup and reproduces two graphic errors: on line 6 Hubert develops the abbreviation qm by the absurd form of ‘que mi’ — similar thing with the first-person ‘sui’ which is turned into ‘sieu’ on line 5 (see Figure 1)24.

Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier didn’t find the poems in an ancient manuscript as she stated it. The preface to the Tour ténébreuse refers to a fictitious manuscript, although its alleged content comes from a real manuscript accessible indirectly through Hubert’s copy, or even a copy of the copy. The Richard the Lionheart manuscript never existed, however the fictional figure of the scholar lending his manuscripts to the author derives from a real activity: the circulation of copied medieval manuscripts in the gallant high society, and even of authentic medieval manuscripts25. Thus, the copy of Manuscript 854 by Hubert circulated beyond the borders of Provence and seems to have interested the Parisian 328milieux, thanks to Mademoiselle L’Héritier26. That’s why I would like to time-travel and pay attention to Hubert’s work more specifically. Before the 1670s, the figure of the troubadour was absent from the literary production of the Parisian gallant and precious circles. From then on, when the Béziers manuscript was composed, Gallaup’s work features increasing connections between medieval manuscripts and modern thought. This aspect of his work is made particularly visible by the complex manipulation and transformation of the manuscripts that he endeavors. Let’s start with the Béziers manuscript.

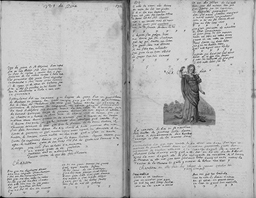

The Béziers manuscript is divided into 2 parts: first the tensos, then vidas accompanied with songs and sirventes27. Schematically, in the 2nd part, each section opens on a troubadour’s name, sometimes illustrated, then followed by a vida, then poems, and ends with a series of remarks in Modern French by Hubert, comparing the text from the manuscript he’s copying to what the printed sources say about it, especially Jean de Notredame. When necessary, Hubert corrects the printed sources. Therefore, Hubert’s copy is a sort of critical edition of the medieval manuscript. Some sections have been illustrated with painted engravings and watercolors from the 17th century, representing both troubadours and trobairitz, male troubadours and their female counterparts.

The 17th-century writing, the use of paper, the scholarly comments and images: such aspects turn the collection into a modernized version of the medieval book which conceptualises the link between its author and the Middle Ages. Hubert’s comments create a critical distance from the figure of authority embodied by Jean de Notredame since 1575. 329Conversely, Hubert modernizes the image of the troubadours by updating their iconography (engravings representing trobairitz, like Azalaïs de Porcairagues as an aristocrat wearing the ruff-collared dress typical of 1580-1620s fashion), and exploiting images referring to bygone days (with Bertrand del Pojet as a knight from the late Middle Ages28, and the Countess of Die dressed in Antiquity-style garments. See Figure 2).

The representation of the poets of the past places them in a continuum that spans from the Antiquity to the 17th century, so much so that the « of Old » conceptualised as a disconnected time by Notredame, becomes an « of Late » with Hubert, as he produces a new uninterrupted history, prone to infuse present times. In other words, this handwritten re-creation of the medieval sources exemplify a type of relation to the Middle Ages that is very close to the one designed by Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier in her Lettre à Melle D. G**. or in her Apothéose de Melle de Scudéry.

Moreover, the staging of the figure of the poetess in Hubert’s copy seems to display only three fundamental aspects of the ethos of the gallant woman. The choice of the three feminine images is significant: the Ancient figure may refer to her letters and her spirit, the pious figure is a reference to her virtue and the figure of the élégante to her taste. The illustration and the arrangement of the sections following the ones in the medieval manuscript put poet and poetesses on an equal footing, poems by men and poems by women, as if the equivalence was produced by the medieval object itself and was only continued through time via the modern object. This aspect echoes the strong desire on the part of the high society milieux to find in Gaulish Antiquity a form of civility that would grant women the same status as men. Here, we are confronted with the elaboration of a book which produces, amongst other things, a reflection on the status of women started in the Middle Ages, which is confirmed in another collection by Hubert, by far more spectacular, the manuscript 408 of the Inguimbertine Library29.

330This time around, we are not presented with a copy but a compilation of authentic manuscripts that Hubert arranged and decorated with engravings from the 16th and 17th century. It features mainly verse: La Doctrine chrétienne (The Christian doctrine), known today as Les Sept Articles de la vraie foi (The Seven Articles of True Faith) by Jean Chapuis30, Le Chevaliers des dames (The Knight of the Dames) by Dolent Fortuné31. Between those texts, two fragments of poems are inserted: five octastichs from the Codicille of Jean de Meun, and thirteen quatrains of the Loys des trespassez lacking their first 48 verses32. The ensemble is adorned with 10 cut and pasted images, engravings from the 16th century, some by renowned masters: Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach the Elder or Albrecht Altdorfer. The Chevalier des dames is at the centre of the collection. It’s a feminist text written in the very particular context of the quarrel surrounding the Roman de la Rose and its misogyny, which it attacks. The arguments explored are essentially of theologic nature: there is a unique feminine nature for women whose model is Virgin Mary; in the Genesis men and women were created equal; the Virgin and Christ are models of virtue for couples in which men and women are equals. Hubert Gallaup de Chasteuil uses this data to build an iconographic cycle that structures his collection as a whole.

The two introductory images of the Adoration associate Virgin Mary and Christ. The following poem consolidates the construction of the couple as Les Sept Articles de la vraie foi summarise seven moments of Christ’s life and end on a praise for Mary, Mother of God. The first section of the 408 collection is thus placed under the patronage of the 331Mary-Jesus couple, early champions of feminism in Le Chevaliers des dames. The illustrations in the Chevaliers participate in the same dynamics. The novel opens on an engraving by Cranach featuring a noble couple riding a horse, an allegorical representation of the couple of the novel, Feminine Nobility and Noble Heart. The iconographic cycle ends on an apparently negligible image representing a room in a noble abode, empty but decorated with a series of feminine statues33. Interestingly, the engraving is taken from an 1538 edition of the Jugement poetic (Poetic Judgement) by Jean Bouchet. It illustrates the narrator-character’s visit to the palace of the « famed ladies », which occasions a praise of illustrious and virtuous women through history since Antiquity34.

This complex collection works as a textual and iconographic cento which recomposes a feminist discourse from manuscripts and heterogeneous medieval texts, with the figure of Virgin Mary as unifying principle. The iconographic cycle inserts medieval texts into an extensive vision of the feminist discourse, which spans from Antiquity to the 16th century, that is to say the century in which Hubert’s father was born (in a significant way, Hubert mentions our « forefathers35 » to refer to medieval poets). As in the Béziers manuscript, Hubert elaborates through this montage a representation of the past times which spans up to the very limit of the present time. Moreover: the final vignette of the famed ladies’ palace36 invites the reader to correlate Hubert’s collection to the genre of illustrious ladies’ portrait gallery, which enjoyed from the 1640s great editorial success (for instance in 1642 and 1644, the two volumes of the Femmes illustres ou les harangues héroïques de Madeleine et Georges de Scudéry. What we know as the Middle Ages is thus conceived, according to Hubert Gallaup, as a period still linked to present times, and medieval textual production as well as its ideological content are still relevant in the 1670s. However, the 332link uniting Hubert to the Middle Ages is not simply intellectual. It also has biographical aspects that are particularly interesting, as they show a personal commitment to medieval manuscripts. Some of his manipulations show a complex staging of Hubert’s own self, his public persona but also his intimate self.

In manuscript 405 from the Inguimbertine Library, Hubert bound an authentic manuscript of the chanson of Beuves de Hantone (Bevis of Hampton) together with a copy of verse excerpts from an Old French translation of the Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius37. But he didn’t just collated the texts together: he also cut manuscript pages to ornament a title page in his own way, as well as an original preface. He made a table of contents composed of 27 folios, which constitutes a proper rewriting of the chanson38. He re-used engravings from the 17th century including one that he would use as postiche frontispiece for the Beuves39.

The engraving is an etching from the 1639 edition of Ariane, novel by Jean Desmarets de Saint-Sorlin (one of the 17th century authors who follows the troubadours in the poets parade of Marie-Jeanne L’Hériter’s Apothéose). The novel takes place under the reign of Nero and tells the adventures of Ariane between Rome, Greece and Sicily. The image represents Ariane accompanied by her uncle Dicéarque welcoming Mélinte, followed by Palamède outside the gates of Syracuse. The text boxes of the original engraving have been cut out. It was then pasted onto a sheet of paper and Hubert inscribed the following text: “Le Romant de Beves & Josienne” (“The Novel of Bevis and Josienne”). He perfected his forgery by adding the names of the heroes of the Bevis next to all the characters on the picture, including the hero’s horse, Arondel. Ariane then becomes Josienne, Melinte Bevis, Dicéarque Hermin and Palamède Thiery.

333The effect of temporal discrepancy is rather striking. The altered engraving represents the young protagonists of a medieval “novel”, wearing 17th century garments and facing people wearing peplos and oriental clothes. Here, the various temporal elements of the iconographic cycle presented in the Béziers manuscript (Antiquity, Middle Ages, 17th century) come together. Through the choice of Desmarets’s novel, which features a feminine heroine, the position of women is highlighted. Finally, the formal composition of the engraving matches the narrative framework of the Beuves de Hantone and illustrates it easily: the oriental outfit works well with the character of Hermin, king of Armenia, and Bevis receives his weapons and his horse from Josienne’s hands. The iconographic structure of a 1639 engraving is thus adaptable to the narrative structure of a medieval story, which once more hints at a continuity between the concerns of old novels and contemporary ones.

Hubert carries out a real editorial work and uses various and heterogeneous matter which he arranges meticulously. What’s the hidden agenda of his work? He wrote that the codex he found was located “en l’une des plus anciennes librairies de la ville de Reims en Champagne” (“in one of the oldest libraries of Reims in Champagne”). And he would not have read it “si les longs et durs loisirs que [s]a mauvaise fortune [lui ont] faits ne [l]’avoint insensiblement atiré a ceste penible lecture40” (“if the long and strenuous idleness that [his] misfortune brought to [him] hadn’t led [him] to that tiresome read”). I thus tried to understand the meaning of the allusion to his “last mishap” and the mention of the city of Reims41. In order to do so, one has to go back to Hubert’s biography. He was one of the most prominent figures of Saint Valentine’s day, February 14th 1659, which marks the beginning of the Aix insurrection against the representative of royal power, the President of Parliament. For his revolt, Hubert is sentenced to exile and the confiscation of all his property. Archives show that he’s kept at the Bastille in 1670 before being sent to Reims, which clarifies the argument of the Preface42.

334The quote that closes the Preface, as well as his Table of Contents — “Deus Nobis hec otia fecit” (“God provided us with idle time”) —, is enlightening. It’s the 6th line from the first eglogue in Virgil’s Bucolics in which Melibeus, expelled by Augustus, needs to leave his land. The collection is thus placed under the patronage of a political exile, which creates a mise en abyme of the situation Hubert found himself caught in. The city of Reims, where Hubert was relegated is mentioned two other times in the collection, more particularly at the end of the copy of the Consolation:

Fin des vers de Jean de Meun contenant en sa translation du livre de confort de philosophie, de Boece, dont il a ausy traduit la prose. Lesquels dit vers ont esté pris de l’ancien manuscrit dudit autheur conservé en la bibliotheque de l’eglise Nostre Dame de Reims43.

“End of the verse by Jean de Meun containing in its translation of the Comfort of Philosophy by Boethius, whose prose he also translated. Those lines were taken from the ancient manuscript by the aforementioned author, kept in the library of the Notre Dame church in Reims.”

During his relegation in Champagne between 1671 and 1672, Hubert dismantled, cut and copied several medieval manuscripts that he bound together. The choice of the two texts of the 405, the Consolation and the Beuves, becomes clearer: a philosophical text aiming at bringing comfort to the author-narrator who has to face adversity and a certain death in Theodoric’s gaol, and a chanson de geste telling the story of the protagonist’s exile, after he is ousted from his land by his own mother. The reader is faced with the manuscript of exile, a manuscript on misfortune converted into leisure (“Deus Nobis hec otia fecit”) which becomes a means of turning the mishap into something positive. Hubert’s 335motto, “Adversante fortuna” (“Facing misfortune”), tells the same story: he attached it to all the books he bought during and after his exile44.

Moreover, according to Hubert himself, the novel can be read like a roman à clef. Indeed, in his Preface, Hubert is very clear about the fact that Bevis is Henry the Liberal, the self-proclaimed sponsor who commissioned the work, as Bevis becomes king of Jerusalem, exactly like Henry:

Il y a grande aparance qu[e le trouvère] a deguisé dans les adventures de son romant la plus part de celles des divers princes de son temps et posible mesme celles du compte de Champagne lequel tout ainsy que le duc Beuves, son heros, mourut roy de Hierusalem45.

“It is conspicuous that the troubadour concealed in most of the adventures he tells in his romance those that happened to the contemporary princes and maybe even those of the Earl of Champagne, like Duke Bevis, died in Jerusalem.”

This reading mode, chosen by Hubert and common for readers of 17th century novels, show his ability to project reality into fiction and to intermingle them, which leads us to read the manuscript as a “manuscrit à clef”, dealing with Hubert himself and his trouble with royal power. In that case, the montage of medieval manuscripts is in direct correlation with the most immediate present, that is to say the author’s topical problems.

Using medieval manuscripts to narrate the misfortunes of the public self is a testament to the strong vectorial value Hubert gives them. If in manuscript 405 they’re just the reflection of an exiled self with which they dialogue through cryptic allusions, there is another collection in which medieval manuscript and intimate self merge into each other, to the point that one becomes absolutely defining for the identity of the other.

I am talking about manuscript 379 from the Inguimbertine Library. It contains, from Hubert’s hand, a free copy of the lives of the troubadours by Jean de Nostredame. To bind them together, Hubert fabricated, or chose, a cover made from rearranged and pasted medieval manuscripts (see Figure 3).

336On the inside back cover, Hubert pasted the table of contents of L’Origine de langue française (The Origin of the French Language) by Fauchet in its 1610 edition, and on the endpaper, the reader can see fragments of texts that are as many autobiographical bits that tell the story of the early stages of the exiles and the stay at the Bastille46:

Je suis parti de ceste ville d’aix ce jourduy 4me may 1668

Ce jourdhuy 18me may 1668 suis arivé a paris

Le 14me Xbre 1669 aresté a la bastille

“I left the city of Aix today 4th of May 1668

Today 18th of May I reached Paris

14th of May arrested in the Bastille”

The style of these brief notes is merely factual, and he often removes the “I”. Sometimes Hubert only writes vague dates. Sometimes his bookbinding work hides parts of his minuscule log: “je suis p…” (“I am p…”). The “I”, sometimes blurred and sometimes altogether removed, tells with modesty a minimalistic and fragmentary personal story.

On the outside covers, Hubert continues talking about him, indirectly, with the same reserve, and resorts to latin citations through which he evokes his misfortune: “Disjectus meus murus est”. Literally, “my wall has been destroyed”. And the reader understands “what protects me has been destroyed”. The quote tacitly reveals the fragility and the weakening of Hubert’s self, his suffering and his deterioration. But in spite of his bad luck, many other quotes display Hubert’s forcefulness and resilience, and show that time and patience will be his allies:

dabit deus his quoque finem47.

Durate et vosmet rebus servate secundis48.

post nubila phoebus.

“god will bring this suffering to an end

Bear with, and keep yourselves, for the happy outcome of the events.

after the clouds, sunshine”

337It is also important to read the phrase murus disjectus as an allusion to the public disgrace that strikes the Gallaup family and to the social ruin of which exile is the instrument. The “Aeneus esto”, present in another margin of the medieval manuscript is the family’s motto. It’s an extract from the first epistle from Horatio to Mecenus49: “Hic murus aeneus esto, nil conscire tibi, nulla pallescere culpa” (“May it be for you a cast iron wall not to have a single thing to reproach yourself for, not to be embarrassed by a single fault”). This motto recalls that moral integrity is the cardinal family virtue amongst the Gallaups. It is the fortress that protects their honour, and it’s displayed on their coat of arms “d’azur, coupé par un pan de muraille à trois creneaux d’argent massonnée de sable, & surmontée de trois étoiles d’or50”. Interestingly, Hubert added the family arms as two wax seals on both sides of the cover (see Figures 4 and 5).

Quotes, family mottos and seal infuse Hubert with a feeling of moral integrity and the firm belief not to have betrayed the king during the Saint Valentine’s Day events51. The medieval manuscript, which keeps the textual memory of the forefathers, also holds the memory of more recent fathers. Above all, it underlines that the family’s aristocratic ethos, from which Hubert constantly draws inspiration, finds its source in bygone times as this short history of the family written by Hubert himself shows:

Gallaup, famille de Naples a pris son origine, en la province de Calabre […] Entre les familles les plus nobles de [Naples] se fait voir celle des Gallaupi ou Gallupi. […] Toux ceux de ce non despuis des siecles immemoriaux ont esté honorés par leurs princes les rois de Naples et ducs de Calabre de beaux emplois et dans les sénats et dans les armées dans lesquels ils ont doné de tres belles marques et de leur valeur et de leur suffisance. Ceste famille a tousjours révéré les letres et ceux qui en sont sortis s’y sont rendus recomandables. Horatio Gallaup en 1317 se faisoit admirer a Naples dans la charge de principal advocat du prince. […] Luigi Gallaup sous le regne de Jeanne fut obligé de quiter son pays. Il passa en France52.

338“Gallaup, family from Naples takes its origins from the province of Calabria. Between the noblest families of Naples, appears that of the Gallaupi or Gallupi. The bearers of that name have been for numberless centuries honored and respected by their lieges the kings of Naples and dukes of Calabria, and they granted them worthy positions in Senates and in armies in which they displayed great bravery and forcefulness. The family has always revered literature and its offspring became experts in the field. In 1317, Horatio Gallaup enjoyed great fame in Naples as he held the position of Crown prosecutor for the prince. Luigi Gallaup, under the reign of Joan, was forced to leave his country. He moved to France.”

The feeling of historic continuity, this time through family history, is also visible here. By filling in the blanks of the manuscripts, Hubert rehabilitates his own dignity by linking the present time to a Middle Ages that would be the warrant of moral nobility. The medieval manuscript, turned into a receptacle for personal memory, offers a space where the “disjectus” self, fragmented by misfortune, proves to be strengthening. The manuscript and the seal are symbolic cast iron walls that protect against adversity. The life story is thus inextricably and intimately interwoven with the medieval manuscript. It is a complex collation which also a recollection of the self legitimated by the Middle Ages.

At the centre of the book, as I said, Hubert placed a copy of the lives of the troubadours, which resonate with the fragments on his own life, as if his own existence was taking the form of a final vida. It would be easy to read in this biographical manuscript the discreet temptation of auto-fiction, with the medieval life stories giving a new form to the intimate self. Through this log, like a travel companion, Hubert brings these stories with him, but also the raw matter that would thwart the exile, a phantasmatic space that enables him to reuse the Provençal space that he was forced to leave behind, a space which enables to invoke the poets’ names and surnames, which are also some of Hubert’s friends’. The book establishes that the noble troubadours are the creators of the love courts, these parliaments, these “plenary courts” (as Hubert, in his quality of lawyer, calls them) where poets were jurists in love cases, in which law serves love. And it’s particularly relevant for him after he was stricken by the king’s disaffection. Here, the political joins the intimate, and it’s specifically the Middle Ages that enable the connection.

339Thus, such manuscript manipulations do not merely show a scholar’s interest for the Middle Ages. They are clearly, in Hubert Gallaup’s case, an instrument of poetic recreation, which graft motifs from ancient times onto contemporary topics. Such topics can be either political (the exclusion of part of the nobility from the State apparatus at the instigation of Louis XIV), social (women and their place in society) or literary (the claim that there is a filiation between medieval and modern literatures). The fact that the manipulation and the compilation of manuscripts could be used as a means to express equally a public self and a damaged intimate self, as well as a means to reshape them, shows that the ancient times are not just considered as the root of present times. The past is a living matter that can irrigate and infuse modern reflection. Hubert found that substance in the medieval manuscripts that he re-inserted and re-articulated, and ultimately manipulated into current affairs.

If we go back to the beginning of my paper, and particularly to the topos of the found manuscript, it seems that it covers a complex, intricate reality. Obviously, it is undeniable that the topos really is a topos as far as Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon’s work is concerned. But in any case it’s not just a literary expedient. It consists in a double movement of real contact with the manuscript and their fictionalization — to the point that her manipulations and truncation of the sources caused disbelief amongst scholars. My point is not to state that one should believe every author’s allegations when they mention a found medieval manuscript. But the example given by the Gallaups show us that the 17th century did more than simply read books from ancient times. Therefore, it seems that a closer scrutiny on the correspondence in learned and high society milieux would enable us to trace discussions and debates on the Middle Ages and manuscript sources. Moreover, the diffusion of medieval manuscripts in the 17th century can only be assessed through a study on book collections from that time, through the annotations and comments made by their owners, and the general manipulations they underwent (collation, collage, cutting…). Hubert’s work in itself is rather spectacular, and modern annotations in medieval manuscripts remain generally more discreet and modest, even though they are enlightening and worthy of interest. My argument here is not to draw any general conclusion from this very specific example that I 340treated quickly. I hope that I could display part of the wide range of major stakes that a study on the concrete reception of the Middle Ages could open a window onto.

Sébastien Douchet

Aix Marseille Université

CIELAM

341

Fig. 1 – Comparison of the editions of Blacatz’s stanza.

Fig. 2 – Structuration of the Béziers songbook

(chapters about Ugo de Pena and the countess of Die, p. 173-174).

Fig. 3 – Carpentras, Bibliothèque-Musée Inguimbertine,

manuscript 379, front cover.

Fig. 4 – Louis Gallaup de Chasteuil. Psaumes de la Pénitence.

(Carpentras, Bibliothèque-Musée Inguimbertine, manuscrit 17), fol. 25r, detail.

Fig. 5 – Carpentras, Bibliothèque-Musée Inguimbertine,

manuscript 379, front cover, detail.

1 A version in French of this paper is available on HAL: S. Douchet, “Réévaluation d’un topos littéraire: le manuscrit médiéval retrouvé. Le cas de Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon et des Gallaup de Chasteuil”, Inventer la littérature médiévale (xvie-xviie siècle), Oct. 2016, Lausanne, Suisse, HAL, https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01592059v1 [retrieved 15/01/2021]. The Gallaup de Chasteuil family is more extensively studied in my forthcoming essay: Une réception du Moyen Âge au xviie siècle. Lectures et usages des textes médiévaux par les Gallaup de Chasteuil (1575-1719), Paris, Champion. See also A. Montoya, “Jouer aux troubadours à l’aube des Lumières (Sévigné, L’Héritier)”, La Réception des troubadours en Languedoc et en France, xvie-xviiie siècle, ed. J.-Fr. Courouau and I. Luciani, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2015, p. 95-108.

2 M. Roussillon, “Les ‘galants troubadours’. Usages des troubadours à l’âge classique”, Réception des troubadours, p. 109-124. This formulation is drawn from Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon’s Lettre à Mme D. G**. See footnotes 7 and 27.

3 Mademoiselle L’H… [Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon], L’Apothéose de Mademoiselle de Scudéry, Paris, Jean Moreau, 1702, p. 27-28 (my translation). I warmly thank Andria Pancrazi and Laetitia Deracinois for their generous patience and for their help in translating this paper into English.

4 N. Edelman, Attitudes of Seventeenth-Century France toward the Middle Ages, New York, King’s Crown Press, 1946, Chapter VI “Appreciation of Medieval Literature”, p. 277-394; J. Voss, Das Mittelalter im historischen Denken Frankreichs. Untersuchungen des Mittelaltersbegriffes und der Mittelalterbewertung von der zweiten Hälfte des 16. bis zur Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts, München, Fink, 1972, Part 2, Chapter 2 d), “Die Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes und ihre Bedeutung für das geschichtliche Denken”, p. 172-179. More anecdotally see S. Douchet, “Les beaux rebuts d’Antoine Bauderon de Sénecé. Présence du Moyen Âge chez un lettré entre deux siècles (1683-1729)”, “Maistre Hues mout bien traita / Nes d’escrire sont las mi doit / L’espasse de mil ans n’i samble pas un jor”. Mélanges médiévistes et encyclopédiques en l’honneur de Denis Hüe, dir. Ch. Ferlampin et F. Pomel, Paris, Classiques Garnier, to be published.

5 This expression, by Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon, is meant to describe the time of Richard The Lionheart in La Tour ténébreuse ou les jours lumineux, Amsterdam, Jacques Desbordes, 1706, Préface.

6 M.-J. L’Héritier de Villandon. “Lettre à Mme D. G**”. Les Bigarrures ingénieuses, Paris, Jean Guignard, 1696, p. 229-245, p. 233-234.

7 “Lettre à Mme D. G**”, p. 235.

8 Marine Roussillon states that the troubadours poems have not been printed during 17th century, and that there was no direct access to them: “la plupart des auteurs qui évoquent les troubadours ne les connaissent qu’au travers des Vies de Jean de Nostredame, de L’Histoire de Provence de César de Nostredame et des quelques pages de Pasquier consacrées à la poésie provençale. Ce sont des textes publiés pour la première fois entre 1575 et 1615 qui sont ‘reçus’ – imprimés et réimprimés, lus, repris, discutés – tout au long du xviie siècle et au début du xviiie” (“Les ‘galants troubadours’”, p. 109). As a matter of fact, Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier reproduces in her preface three poems attributed to King Richard The Lionheart and to Blondel de Nesle. Two of those poems have been borrowed to Jean de Notredame and Claude Fauchet (See Montoya, “Jouer aux troubadours”, p. 105-106).

9 Roussillon, “Les ‘galants troubadours’”, p. 109.

10 Carpentras, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, manuscripts 634 and 636. The first one, by Hubert himself, was written c. 1672; the second one is the sales catalogue of the Gallaup library (the auction took place in 1705).

11 In the introductory text to his catalogue, Hubert complains about the loss of many books before he inventoried his library: “La petite librairie de nostre maison a soufert des grandes penes en divers temps. La plus grande fut en la mort de mon ayeul Louis de Gallaup. Monsieur François de Gallaup, mon saint oncle, en emporta une partie dans sa solitude du Mont Liban. Au premier voyage que je fis a Paris après la mort de feu Jan de Gallaup, procureur general des comptes, mon père, on m’en enleva beaucoup. Mais dans le dernier malheur qui m’a aceuili, il s’en est perdu deus cens volumes à mon retour en la province, je les ay reveus et en ay dressé le présent inventaire ou j’ay inseré plus de quatre cens volumes que j’ay apportés de mes voyages et qui sont marqués de ces mots: adversante fortuna”, Carpentras, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, manuscript 634, p. 1.

12 M.-J. L’Héritier de Villandon, La Tour ténébreuse ou les jours lumineux, Amsterdam, Jacques Desbordes, 1706, Préface.

13 A. Jeanroy, review of L. Wiese, Die Lieder des Blendel de Nesle, Romania, 34, 1905, p. 329, footnote 1.

14 La Tour ténébreuse, Préface.

15 Chansonnier I, Bibliothèque nationale de France, français 854, fol. 109v, col. 1.

16 M.-J. L’Héritier de Villandon, L’Érudition enjouée, ou nouvelles sçavantes, satyriques et galantes, écrites à une Dame françoise, qui est à Madrid, Paris, Pierre Ribou, september-october 1703, p. 4.

17 L’Héritier de Villandon, L’Érudition enjouée, p. 9.

18 P. Gallaup de Chasteuil, Discours sur les arcs triomphaux dressés en la ville d’Aix à l’heureuse arrivée de monseigneur le duc de Bourgogne et de monseigneur le duc de Berry, Aix, Jean Adibert, 1701. In 1703, in her Letter to a Spanish woman, Marie-Jeanne l’Héritier advocates on behalf of Pierre Gallaup de Chasteuil who, in his Discours des Arcs, traces the creation and functioning in Provence of the medieval love courts. Indeed, Pierre Gallaup was mocked and attacked by Pierre-Joseph de Haitze, an historian who denied the existence of love courts. Thus, Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier participated to a historical quarrel. This love courts quarrel provoked many debates amongst scholars and gens de lettres. See M. Roussillon, “Querelle des cours d’Amour”, http://base-agon.paris-sorbonne.fr/querelles/querelle-des-cours-d-amour [retrieved 15/01/2021].

19 P. Gallaup de Chasteuil, Discours sur les arcs, p. 21 (my translation).

20 Chansonnier de Béziers, Béziers, Cirdòc – Médiathèque occitane, manuscript 13, p. 5.

21 G. Brunel-Lobrichon, “Le chansonnier provençal conservé à Béziers”, Actes du premier congrès international de l’Association internationale d’études occitanes, ed. P.T. Ricketts, London, Westfield College, 1987, p. 139-147. I add that in his Discours, Pierre gives another hint: “La première tençon, qui se trouve dans ce Manuscrit, est une dispute entre trois Troubadours, qui sont, D’en Savaric de Mauleon, en Gausselin Faidits, & en Nugo de Baccalaria, tous trois distinguez par la qualité, ou par le sçavoir” (P. Gallaup de Chasteuil, Discours sur les arcs, p. 21) which matches songbook I (Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscrit 854, fol. 152r: “Den savarics de maulleon. et en Gausselins faiditz. et en nugo de la bacalaria”).

22 Amongst the three different handwritings of this copy, I have undoubtedly identified Hubert’s handwriting (see my upcoming essay Une réception du Moyen Âge au xviie siècle, and compare Béziers, manuscript 13 with Carpentras, manuscript 634). Furthermore, in fol. 140r of the Béziers songbook, Hubert writes in his commentary on the vida of Jaufré Rudel: “Ce poête a mis par escrit la guerre de Tresia contra Lous, reis d’Arles, dont j’ay le manuscrit. Il s’agit du texte que l’on a appelé le Roman d’Arles, ou Roman de Tersin, qui n’est conservé qu’en deux exemplaires et deux copies”. Yet, the two mentioned copies belonged to the Gallaup family: the first one, copied by Jean de Nostredame, includes marginal notes by Pierre Gallaup (see J.-Y. Casanova, Historiographie et Littérature au xvie siècle en Provence: l’œuvre de Jean de Nostredame, Turnhout, Brepols, 2012, p. 202); the second one, copied by Jean Gallaup, father of Pierre and Hubert, is a copy with variants of Jean de Nostredame’s copy (thus, Nostredame’s manuscripts must have belonged to the Gallaup library at the time of Jean). This copy is mentioned in Hubert’s personal catalogue (Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, manuscript 634, p. 58). The two copies can still be found in the Inguimbertine Library (where is kept most of the Gallaup fund, which I could reconstitute): Nostredame’s copy is manuscript 537, fol. 3r-12r; Gallaup’s copy is manuscript 1883, fol. 2r-6v). Further details in S. Douchet, « L’Hystoyre de la guerre d’Arles. L’épisode de Tersin dans la Chronique de Provence de Jean de Nostredame (ca. 1575) », De la pensée de l’histoire au jeu littéraire. Études médiévales en l’honneur de Dominique Boutet, dir. S. Douchet, M.-P. Halary, P. Moran, S. Lefèvre, J.-R. Valette, Paris, Champion, 2019, p. 870-881. The first person pronoun “je” used in the Béziers songbook refers to Hubert Gallaup. Therefore, the attribution of the songbook on the site www.occitanica.eu is erroneous (see http://www.occitanica.eu/omeka/items/show/10865 [retrieved 15/01/2021]: Bruno Marty’s commentary must be fully revised, as I demonstrate in my upcoming essay Une réception du Moyen Âge au xviie siècle).

23 A. Jeanroy, “Review of Wiese”.

24 More accurately, Jeanroy is mistaken: L’Héritier didn’t copy Blacas’ canso as in “I”, fol. 109r, but his son Blacasset’s canso, that is to be found in “I”, fol. 109v. Both poems have a very similar content, which explains why Jeanroy was mistaken.

25 Pierre Gallaup, in a letter to Melle de Simiane, dated August 19th 1711, declares he consulted: “un manuscrit que j’avois gardé quelque temps à Paris et que j’avois tiré de la bibliothèque du Roy et dont j’avois fait transcrire ou ecrit moi même ce que j’y trouvai de plus curieux et de plus particulier” (Avignon, Bibliothèque Ceccano, manuscript 2349, fol. 327r).

26 The existence of a gallant and scholarly network linking Paris and the Provence remains to be studied. But the L’Héritier-Gallaup connection is a brilliant evidence of its reality, as well as the creation of a wording that shapes the image of the “troubadour”. Indeed, the phrase “galans troubadours” spread beyond the Lettre à Mme D. G**. In an unpublished epistle dedicated to Pierre Gallaup de Chasteuil (received on the 6th of August 1707), the poet Antoine Bauderon de Sénecé praises the study on the troubadours by his erudite and gallant friend. In this epistle he lauds the “galants Troubadours” […] “ces maîtres respectés de Pétrarque et de Dante” (to be published in my essay Une réception du Moyen Âge au xviie siècle). See my article: “Les beaux rebuts d’Antoine Bauderon de Sénecé”.

27 From p. 5 to 60: tensos section. From p. 61 to 223: vidas section, entitled “Aqui son escrig Las vidas e Li noms Dels Trobadors L’un apres L’autre, que An trobadas Las cansos e Los sirventes Qui sont en a quest Libre”.

28 See Chansonnier de Béziers, ms. cit, p. 171, 145 and 149.

29 See, for a more detailed analysis, my article (co-written with Valérie Naudet): “‘Couper avec des cizeaux les portraits de nos trouvaires’. Défiguration et reconfiguration d’objets manuscrits médiévaux au xviie siècle”, Lire les objets médiévaux. Quand les choses font signe et sens, ed. F. Pomel, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2017, p. 253-294, and our descriptive record: “Le manuscrit 408 de la Bibliothèque Inguimbertine de Carpentras: notice”, Le Goût de l’Orient. Collections et collectionneurs de Provence, ed. A. Bosc and M. Jacottin, Milano, Silvana Editoriale, 2013, p. 62-63.

30 See J. Chapuis, Les Sept Articles de la foy, in: G. de Lorris, J. de Meun, Le Roman de la Rose, ed. D. Martin Méon, Paris, Didot, 1814, vol. III, p. 331-395.

31 See Le Chevalier des dames du Dolent Fortuné. Allégorie en vers de la fin du xve siècle, ed. J. Miquet, Ottawa, Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa, 1990.

32 The Loys des trespassez have been edited in an incunabulum where they follow the Codicille of Jean de Meung as well. See J. de Meung, Les Loys des Trespassez, avecques le pelerinage de maistre Jehan de Mung, Bréhan-Loudéac, Robin Foucquet and Jean Crès, 1485. This incunabulum has been described by Arthur Le Moyne de Laborderie in L’Imprimerie bretonne au xve siècle, Nantes, Société des bibliophiles bretons et de l’histoire de Bretagne, 1878, p. 18 sq.). Jean Sonet only mentions a single manuscript for this text in his Répertoire de prières en ancien français, Genève, Droz, 1956, item 248, p. 44: Bibliothèque municipale de Toulouse, manuscript 821, fol. 53v. Thus, in all likelihood, the Carpentras fragment is the second known manuscript of this text, a prayer for the dead (transcribed by Félix Soleil in Les Heures gothiques et la littérature pieuse aux xve et xvie siècles, Rouen, Augé, 1882, p. 177-180).

33 Carpentras, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, manuscript 408, fol. 117r.

34 The Jugement poétic of Jean Bouchet describes “le grand palays faict pour les claires dames”. This palace is adorned with one million sculptures made by Pygmalion and contains “tables” on which are inscribed the names of the “dames d’honneur”, “dames hebraïcques”, “dames ethniques” and “dames chrestiennes” (J. Bouchet, Jugement poetic, fol. 30r to 31r).

35 Carpentras, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, manuscript 405, Préface to the Beuves, fol. 2r.

36 See the vignette in my article, “‘Couper avec des cizeaux…”, p. 284. Ref.: Carpentras, Bibliothèque-Musée Inguimbertine, manuscript 408, fol. 117r, pasting of a woodcut from Jean Bouchet’s Jugement poétic de l’honneur fémenin et séjour des illustres, claires et honnestes dames. (Poitiers: Jehan et Enguilbert de Marnef, 1538).

37 Translation by Renaud de Louhans. See, for a comprehensive description and a deeper analysis of this manuscript, my articles (co-written with Valérie Naudet): « Vieux roman: comprenne qui pourra… Étude du manuscrit 405 de la Bibliothèque Inguimbertine de Carpentras », Le Manuscrit unique. Une singularité plurielle, dir. É. Burle-Errecade and V. Gontero-Lauze, Paris, PUPS, 2018, p. 89-113.

38 Table of contents: fol. 112r to fol. 139v; frontispiece: fol. 6r.

39 See the engraving in my article, “‘Couper avec des cizeaux…”, p. 273. Ref.: Carpentras, Bibliothèque-Musée Inguimbertine, manuscript 405, fol. 6r, pasting of a copper engraving of Abraham Bosse from Jean Desmarets de Saint-Sorlin’s Ariane (Paris, Mathieu Guillemot, 1639).

40 Carpentras, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, manuscript 405, fol. 2r and 2v.

41 See footnote 12.

42 The Saint Valentine’s revolt has been accurately studied by René Pillorget in Les Mouvements insurrectionnels de Provence entre 1596 et 1715, Paris, Pedone, 1975, p. 751 sq. Concerning the Bastille and Hubert’s exile, manuscript Arsenal 12472 contains the following letter: “Le 19 décembre 1670 / Mons.r de Besmaus, ayant resolu de donner la liberté aux S.rs de Chasteuil et de Mongué que vous tenez prisonnier par mon ordre dans mon Chasteau de la Bastille, aux conditions que celuy cy se retirera à Apt en Provence, et l’autre en ma ville de Reims en Champagne, et qu’ils y demeureront jusques a nouvel ordre. Je vous fais cette lettre pour vous dire de les laisser sortir aussy tost que vous l’aurez receüe, priant Dieu qu’il vous ayt Mons.r de Besmaus en sa sainte garde. Escrit a Paris le xix.e Jour de Decembre 1670”. On the back of the letter is written: “A Mons.’ De Basmaus / Capitaine et gouverneur / De mon bastion de la / Bastille” as well as a later note: “pour la sortie de messieurs de Chasteuil et de Mongué le 21me xbre 1670 signé Louis et Colbert”. Hubert has been imprisoned in the Bastille on the 14th of December 1669 (see infra my study of manuscript 379).

43 Carpentras, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, manuscript 405, fol. 165r.

44 See footnote 13.

45 Carpentras, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, manuscript 405, fol. 4r.

46 A picture of these notes can be seen in my upcoming essay Une réception du Moyen Âge au xviie siècle.

47 Virgil, Æneid I -199.

48 Ibid., I -207.

49 Horatio, Epistles, 1.1.61.

50 L’État de la Provence dans sa noblesse, Paris, Pierre Aubouin, 1693, vol. 2, p. 114.

51 See Hubert’s request to the King (factum kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, shelfmark FOL-FM-6423). According to the BnF bibliographic record, this document dates back to1670. But Hubert mentions his “absence de 14 années” from his flight in 1659. Thus, the factum dates back to c.1673, which matches the end of Hubert’s exile in Champagne.

52 Carpentras, Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, manuscript 386, fol. 30r-v.