La musique et ses pouvoirs dans l'Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499)

- Publication type: Journal article

- Journal: Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes / Journal of Medieval and Humanistic Studies

2020 – 1, n° 39. varia - Author: Godwin (Joscelyn)

- Abstract: In Colonna’s dream-novel, an unearthly song initiates an altered state of consciousness in the protagonist. He finds himself in a pagan fantasy world ruled by Cupid and Venus, in which every situation has its appropriate musical accompaniment. Instruments, ensembles, and their effects on soul and body are described with unusual fullness. Music thus serves as an adjunct to theurgy, putting man in communication with the gods, and as a manifestation of divine harmony or Love.

- Pages: 263 to 276

- Journal: Journal of Medieval and Humanistic Studies

- CLIL theme: 4027 -- SCIENCES HUMAINES ET SOCIALES, LETTRES -- Lettres et Sciences du langage -- Lettres -- Etudes littéraires générales et thématiques

- EAN: 9782406107422

- ISBN: 978-2-406-10742-2

- ISSN: 2273-0893

- DOI: 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-10742-2.p.0263

- Publisher: Classiques Garnier

- Online publication: 07-14-2020

- Periodicity: Biannual

- Language: English

- Keyword: Francesco Colonna, musique, modes, polyphonie, pratique de la performance, instruments, Venise, Renaissance

MUSIC AND ITS POWERS IN THE HYPNEROTOMACHIA POLIPHILI (1499)

The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (“Sleep-Love-Dream of Poliphilo,” henceforth HP) is an illustrated prose epic, or fantasy novel, published in Venice by the humanist printer Aldus Manutius in 1499. It is almost certain that the author was Francesco Colonna (c. 1433-1527), a priest and religious of the Dominican Order who lived first in Treviso, then at the monastery of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. Many attempts have been made, and continue to be made, to propose other candidates for authorship, but none has met with general acceptance1. Likewise the design for the 172 woodcuts has been attributed to numerous artists, with the partial consensus that they originated in the circle of Andrea Mantegna.

Aldus’s original folio edition is a superb example of early printing, and the integration of the illustrations with the text a landmark in book design. Colonna’s work was translated into French in 1546, with all the illustrations redrawn in Mannerist style. In 1592 Sir Robert Dallington, an Elizabethan courtier, issued a rough version of the first two-fifths of the book. A complete English translation was finally published in the quincentenary year of 19992. Quotations and page references here are from that edition, together with the original foliation by signatures.

This is not the place to summarize the convoluted storyline of Poliphilo’s quest for his beloved Polia, set in an idealized classical world ordered according to the pagan hierarchy, in which the gods and demigods are co-present with humans. Thanks to bibliophiles and the 264many articles and whole books devoted to the HP by modern scholars3, Colonna’s obsessive interests in architecture, sculpture, interior decoration, gardens, cemeteries, costume, classical mythology, linguistic invention, and the charms of nymphs are well known, but none has hitherto treated the role of music in his story. While Colonna does not speak of harmonic proportions or other mathematical aspects, as he does when treating architecture, he was obviously a discriminating music lover and a keen observer of it from a non-technical point of view. Music appears in over fifty places in the HP, adding up to a minor treatise on its types, uses, and effects.

As in Dante’s Inferno, the curtain rises on a dark wood where the narrator has lost his way. Exhausted by thirst, Poliphilo comes upon a spring:

But just as I was raising my hands with the delicious and longed-for water to my open mouth, at that very instant a Doric song penetrated the caverns of my ears – I was sure that it was by Thamyras of Thrace. It filled my disquieted heart with such sweetness and harmony that I thought it could not be an earthly voice: it had such harmony, such incredible sonority and such unusual rhythm as I could never have imagined, and it certainly exceeded my power to describe it. Its sweetness and charm gave me much more pleasure than the little cup I was offering myself, so that the water began to run out between my fingers. My mind was as though stupefied and senseless, my appetite sated, as, powerless to resist, I loosed my knuckles and spilled it on the damp earth. (p. 17/fol. a5r)

After a further scramble through the undergrowth to find the source of the song, Poliphilo gives up and falls into an exhausted sleep. When he wakes he is in another world.

“Musica dicitur a moys, quod est aqua” (Music is named from moys, which means water): John of Garland’s etymology4 comes to mind in this first scene, as Poliphilo’s thirst is slaked by a “water that does not wet the hands,” to use the alchemists’ expression. Music heard in dream or trance may open the door to transcendent experience, but, like the song of the “damsel with a dulcimer” in Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, cannot 265be recaptured in the waking state. Poliphilo will spend the next four hundred pages in a dream-world where music is not just an ornament to life, but the very stuff of existence. Nearly every situation and action there has its appropriate musical accompaniment; music and dance are the normal states and activities, while others merely interrupt them.

Poliphilo’s fortunes change when he meets a group of maidens singing to the “lyre”. The illustration shows a viola da braccio, the preferred instrument of humanists such as Marsilio Ficino who sought to recapture the extempore performance of the ancients. In Renaissance iconography it often stood in for the ancient instrument; Apollo plays one in Raphael’s Parnassus5. The maidens adopt this curious interloper – for Poliphilo is the only mortal male in their world – with teasing and blandishment. In a mildly salacious scene they take him to a bath-house, then head for the palace of their ruler, Queen Eleuterylida (“Liberal/Bountiful”), singing “a rhythmical song in the Phrygian mode about a facetious metamorphosis: a lover wanted to turn himself into a bird with magic ointment, but used the wrong jar and was transformed into a common ass” (p. 86/fol. e7v).

The Phrygian is the only mode beside the Dorian that Plato permitted for his ideal republic: Dorian and Phrygian “imitate the accents of brave men, both in misfortune and prosperity”6. Poliphilo is not only able to tell the modes apart by ear, but his classical erudition embraces the Thracian Thamyris (or Thamyras, inventor of the Dorian mode, rival of the Muses, teacher of Orpheus) and alludes to the recently (1469) published Metamorphoses, or The golden Ass by Lucius Apuleius, which the author ransacks for its recondite Latin vocabulary.

The great courtyard of Queen Eleuterylida’s palace, as Poliphilo notes with approval, is decorated with images of the seven planets: their qualities, triumphs, harmonies, and “the transit of the soul receiving the qualities of the seven degrees, with an incredible representation of the celestial operations” (p. 95/fol. f4r). This refers to the Hermetic and Neoplatonic system, according to which the soul passes through the planetary spheres on its descent into birth, receiving the qualities of 266each as it goes. A ready parallel in our world is Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara (1469-1470), which as the name (“flee boredom”) suggests served as a retreat from the main palace of the Este family. The Salone dei Mesi (Hall of the Months) is decorated with a sumptuous iconography of planetary triumphs, the astrological decans, and the earthly activities ruled by them. Why should that be thought appropriate for places dedicated to freedom and pleasure? In an analysis of the Schifanoia frescoes, I suggested that they represent Duke Borso d’Este, who is pictured in the scenes of daily life, as the good ruler who “ensures that the earthly life of all his subjects is conducted in conformity with the heavenly order”7. This was also the theme of Marsilio Ficino’s De vita coelitùs comparanda, the third book of his treatise on Life (1489). Likewise in Queen Eleuterylida’s court, exquisite pleasures such as the eight-course banquet and the after-dinner entertainment obey precise ritual conditions, like an operation of ceremonial magic.

Twelve maidens, in two groups of six, provide the music. “At every serving or change of courses they changed their music and their instruments, and while we were eating, others warbled sweetly with an angelic or siren-like song” (p. 102-103/fol. f8r). The instruments are pseudo-classical: “curved trumpets” and flutes; the singers use “the Aeolian mode, so sweetly as to make the Sirens sigh, accompanied by reed pipes and double flutes such as Troezenius Dardanus never invented” (p. 108/fol. g2v). After the feast, dancing maidens perform a ballet in the form of a chess-game, 16 dressed in gold on one side and 16 in silver on the opposite side. I do not know of a livelier description of dancing to fifteenth-century concerted music. Here are some excerpts:

The musicians began to play on three instruments of strange invention, very well in tune and in ensemble, with sweet chords and melodious intonation. At the rhythmical beat of the music the dancers moved on the squares, agile as dolphins, as the king directed: they turned around, duly honouring the king and queen, then jumped onto another square, making a perfect landing… When the first ballet game was finished, all moved back to their own squares… [In the second game] the musicians speeded up the beat and the movements and gestures of the agile dancers went faster… and when one was captured, she lifted her arms and clapped her palms together. Sporting and turning in this fashion, the first side was victorious once more. All were positioned in their places for the third ballet, then the musicians played in 267a still faster tempo and in the exciting Phrygian mode, the one supposedly invented by Marsyas of Phrygia… They displayed such discipline and faultless order that if the rhythm of the expert musicians briefly accelerated, all the dancers would do no less with their movements, owing to the consonance of harmony with the soul; for it is chiefly and principally through this that there exists the concord and agreement by which the body is sympathetically disposed. (p. 119-121/fol. g8r-h1r; italics mine)

The italicized phrase is the philosophical core of Colonna’s approach to music, as it is of Greek and Medieval theory. The effect of music is on the soul, or, in the more elaborate system of Ficino, on the spiritus that links soul and body. According to the doctrine of correspondence that is the sine qua non of magic, action on one level of being – here that of sound – resonates on another – that of the immaterial but harmonically constituted soul. That in turn transmits its resonance to the physical body, which responds instantaneously, bypassing the rational mind. Again there is the assumption that pleasure and beauty result from discipline and harmony of the microcosm with the macrocosm.

Queen Eleuterylida sends Poliphilo on his way with two guides, Logistica (“Reason”) and Thelemia (“Freewill”). As in The Magic Flute, the questing hero is faced with a choice of three portals, here giving access to “Gloria Dei” (Glory of God), “Gloria Mundi” (Worldly Glory), and “Mater Amoris” (Mother of Love)8. Logistica urges him to choose the second, and to encourage him she seizes the lyre from Thelemia and sings in the sturdy Dorian mode, but to no avail. He chooses the door that leads to the realm of Venus, and the Dorian is heard no more. The songs from now on are in the sweet Lydian and the jubilant Ionian modes.

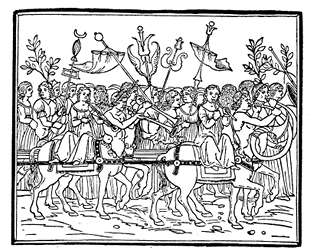

A series of triumphs follows, representing the loves of Jupiter, each one accompanied by musical nymphs. In the Triumph of Europa there are six nymphs riding on centaurs, three facing to the left and three to the right, playing “musical instruments in heavenly harmony together” (p. 161/fol. k5r). The illustration shows tambourine, rebec, and double pipe. Four of the centaurs are also playing: two have golden trumpets and two “ancient curved horns” like the Roman buccina. As always in literary or iconographic sources, any resemblance to actual musical 268practice is dubious, but we can assert that Colonna habitually imagines music-making in consorts of six. In the Triumph of Leda the nymphs play “different kinds of instruments blending in a magnificent consort” (p. 165/fol. k7r); tambourine, bladder-pipe, and a kind of psaltery-lyre are shown, while the white elephants on which they ride “trumpeted softly”.

The nymphs of the Triumph of Danaë are mounted on unicorns, playing “marvelous antique wind instruments, with incredible breath-control” (p. 169/fol. l1r). In the Triumph of Semele there are no riders on the panthers that draw the chariot of her son Dionysus, but a crowd of naked or semi-naked Maenads “played cymbals and flutes, and celebrated the sacred orgy with shouts and Bacchic hymns, as in the triennial festival” (p. 176/fol. l4v). These were not the only musical events: a throng of youths and nymphs precede the triumphal chariots. “Some were playing brass instruments of various shapes and demands on the breath, with bent or straight tubes” (p. 178/fol. l5r). Note Colonna’s attention to practical details. He continues: “There were also loud wind instruments, while others sang to stringed instruments with heavenly melody, singing of ineffable pleasures and endless delights exceeding all 269that the human mind could imagine.” These subsidiary choirs include a group of the Nine Muses with their leader Apollo, Others dance as they sing with “lyres and dulcet instruments”, or sing “voluptuous hymns with the resonant cithara”.

Fig. 1 et 2 – The Triumph of Europa, from Francesco Colonna,

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1499), fol. k5v-k6r.

The display of Love’s powers continues down the divine hierarchy with a Triumph of Vertumnus and Pomona, humble patrons of agriculture. Their chariot is drawn by four goat-footed fauns, flanked by Hamadryad nymphs bearing mattocks, hoes, and sickles. Although one is shown blowing a straight trumpet, another playing a lyre, most of the nymphs are “dancing, clapping, and jubilating” (p. 190/fol. m4r). The procession ends at a shrine to Priapus, the ithyphallic god of fertility. Here the nymphs sacrifice a donkey, cutting its throat and spattering blood, warm milk, and wine around, while “in rustic style they sang nuptial and bawdy songs, and played their peasant instruments with 270the utmost joy and glory, celebrating with jumping, leaping and earnest applause, and with loud female voices” (p. 194/fol. m5v). Lastly Poliphilo meets the Naiads of the watery dells and the woodland Pans of Arcadia, with the demigods of forest and mountain and their shepherd attendants: “They had old-fashioned instruments of reed and cane, and in place of trumpets, flutes of bark in serpent-form with a strange sound” (p. 196/fol. m6v).

Of all the mottoes, hieroglyphs and inscriptions in which the HP abounds, the dominant one is “Amor vincit omnia” (Love conquers all). The triumphs are intended to show that even Jupiter cannot resist its power, which reaches down from Olympus through mortals to the raw procreative force of animal and vegetable nature. But there is one other irresistible power in the cosmos: that of music, which accompanies the spectacle at every stage. Here is a passage succinctly blending the two powers, from the description of the young lovers surrounding the triumphs:

Some were singing amorous verses together, their halting voices interrupted by sighs from their inflamed bosoms, full of soft accents that would have made hearts of stone fall gently in love, or tamed the hostility of impassable Mount Caucasus. They would have achieved everything that the lyre of Orpheus could do, or the accursed face of Medusa, and rendered every horrible monster benign and tractable, even calming the ceaseless motion of raving Scylla. (p. 183/fol. l8r)

Many a music treatise opens with a laus musicae, recounting the marvelous effects that music had in ancient times, and regretting that the moderns are unable to equal them. The HP mentions the standard examples: Orpheus, with his power over the natural world and even over the chthonic divinities; Arion, whose song summoned a dolphin to carry him to safety; Timotheus, who used music to manipulate the emotions of Alexander the Great; Hermes, charming the hundred-eyed Argus to sleep, so that Jupiter could seduce Io; and Demodochus, the blind bard whom Odysseus hears in the fairyland of Phaeacia. One outstanding example is absent: that of David, who cured King Saul’s melancholy with his harp, since this pagan story is purged of almost all biblical references. A rare and quirky exception is at the Temple of Venus Physizoa, one of the many buildings that fill Poliphilo with ecstatic admiration and lead to pages of intricate architectural description. On the very top of the temple dome is a contraption with four bronze jingle-bells containing 271steel balls, hung on chains. When the wind blows, they bump against a bronze sphere, making a sweet and loud sound that “perhaps surpassed that of the Temple in Jerusalem, which had brass vases hung by chains from the top to scare away the birds” (p. 210/fol. n6r).

In Venus’s temple Poliphilo and Polia undergo a solemn marriage ceremony, celebrated by a High Priestess with the assistance of six virgins and a girl acolyte. It is part reconstruction of ancient Roman ritual, part parody of Christian liturgy. One might call it a magical operation, especially as its object is to achieve mutual love, but strictly speaking it is theurgy, as we shall see.

Early in the ceremony, two white doves are burned, “which had previously been diligently plucked and their throats cut upon the sacrificial table, opened dorsally with the knife, and tied together with knots of golden thread and purple silk, the warm blood being preserved with great veneration in the special vessel” (p. 226/fol. o5v). After this, the High Priestess acts as precentor, chanting from the ritual volume held by the acolyte, with the attendants responding in alternation. She then leads the company in a dance, accompanied by two virgins playing on Lydian flutes and in the Lydian mode:

They danced following the tempo, the steps and the positions, equally spaced from one another and leaping like solemn and religious Bacchantes, harmonizing their voices with the instruments and producing from their virgin breasts an incredible symphony that echoed beneath the domed cupola. Circling the burning altar, they intoned rhythmically “O holy fragrant fire, Let hearts of ice now melt. Please Venus with desire, And let her warmth be felt”. (p. 226/fol. o5v)

The result of this incantatory round-dance is the apparition of a little winged “god-sent spirit” from the smoke of the sacrifice. It appears with a heart-stopping explosion, flies thrice around the altar, and vanishes in a lightning flash (p. 226-227/fol. o6r).

Other common magical topoi occur in this scene, as when the High Priestess has Polia draw in the sacred ashes “certain characters, with care and precision just as they were painted in the volume of pontifical ritual”. The obstacles to love are exorcised, with aspersions during which the nymphs sing hymns. The High Priestess strikes the altar thrice with her sacrificial wand, “with many arcane words and conjurations”. Two swans are sacrificed, while the virgins sing “rhythmical odes”. The climax of the ceremony is the apparition of a fully fruiting rose tree, filling 272the sanctuary and bearing “rounded fruits of marvellous fragrance that were white tinted with red”. The couple communicate, together with the High Priestess, by eating these fruits “with the prescribed ritual and the deepest sincerity of heart” (p. 233/fol. p1r). The effect on Poliphilo is instant: “I began to know directly and actually to feel the graces of Venus, the power that they wield over earthlings, and the joyful reward of those who battle their way boldly into those delicious realms through victory in the amorous battle” (p. 234/fol. p1v).

Thus he attains the goal of theurgy, which uses ritual to obtain direct knowledge of the gods.

The next part of the book takes Poliphilo and Polia on a voyage to Venus’s realm, the Island of Cytherea – destined to inspire artists (Watteau), writers (Nerval, Baudelaire), and even composers (Debussy) in the centuries to come. The captain of their bejeweled boat is the divine child Cupid himself, spreading his rainbow wings to catch the wind. The crew of six sailor-nymphs row with ivory oars in golden rowlocks, but that is the least of their talents:

Now the sailor-nymphs began to sing, with sweetest notes and heavenly intonation quite different from human ones, and with a vocal skill beyond belief, a lovely concert with harmonized voices and bird-like melody… fluttering their tongues against their sonorous palates and dividing and trilling even the shortest flagged notes into two or three. First they sang in pairs, then in threes, then in four parts and lastly in all six… They sang to stringed instruments, celebrating the benefits and qualities of love, the merry affairs of great Jupiter… the dainty fruits of Hymen, performing them rhythmically in poetic modes and metrical melodies… One could see the vocal spirits passing through their white throats, for this was celestial flesh of divine composition, as transparent as crystalline, refined camphor tinted with scarlet. (p. 285-286/fol. s3r-v)

Colonna’s eye and ear for detail tell us more, as the boat speeds on “like a weightless water-insect” over the unfurrowed sea: “The lovely oarswomen sang a jubilant song in the Ionic mode, and divine Polia sang a solo cantilena, without the others, in the slightly different but comparable Lydian mode… celebrating the supreme goodness of the holy Mother, Venus Erycine, and sang of the lovable tricks of her Son, who was present” (p. 289/fol. s5r).

Poliphilo’s progress through Cytherea is seldom silent. Venus’s island is populated by youths and maidens who spend their time “playing 273instruments, singing, dancing, chatting merrily, enjoying pure and sincere embraces, tending their ornaments and their persons, composing poetry, and the maidens intent and dedicated to their handwork” (p. 314/fol. u1v). During the final triumph, that of Cupid, curved horns play together with golden trumpets; there are “noble and extraordinary instruments” such as organs, sistra, and iron triangles. A group of pipe-and-tabor players is described in unusual detail, with “noisy, pattering tabors hanging from their left hands… whilst their slender and nimble fingers alternately opened and closed the holes of the single pipe… which made the cheeks bulge attractively and turned them the color of apples” (p. 342-343/fol. x7v-8r). Colonna reassures us that the various bands did not all play together, but each played in sequence and was assigned its proper place in the procession. Here we are on more familiar historical ground, knowing the models of royal entries, wedding celebrations, etc.

At the center of the island is a circular theater with a seven-sided fountain. Three choirs of nymphs, constantly dancing, wind their way around its arcades “accompanied by the superb sound of four golden sackbuts and four mild-sounding shawms: soprano, alto, tenor and bass. They were made on the lathe from red, yellow and white sandalwood and from black ebony, not lacking many ornaments of gold and gems. With the sweetest homogeneous sound and with very fast rhythms, they played an elaborate symphony that was most delightful, with satisfying cadences and mutual imitation” (p. 356/fol. y6v). This recalls the standard ensemble of loud instruments used from the fourteenth through the fifteenth century to accompany feasting and dancing, but the many pictorial representations usually show two shawms and a slide-trumpet or sackbut, never an octet! Ariani and Gabrieli’s commentary on the scene is on a higher level, with rhetoric and erudition befitting its subject:

Here Poliphilo’s ecstasy returns – raptus, excessus mentis – caused by the perception of an “unfamiliar harmony,” the celestial music that emerges from the amphitheater of light at whose center is the Fountain of Venus. Colonna evidently wished to concentrate around Venus all the foundations of the harmonia mundi: the cosmic mirroring from the “bass” (the “abyss” of the obsidian pavement) to the “alto” (the “deep heaven”): the amphitheater as gemstone and mirror, seeming to concentrate all the crystalline light of Cytherea, in which everything is duplicated between reflected reality and ideal reality; the prodigious eurhythmy of the dances, the unheard-of harmony of voices and instruments, symbolizing the vis unitiva of the Genetrix (according to the 274great hymn of Lucretius, frequently mentioned, to which Colonna seems to have wished to give a true symbolic “visualization,” perceptible to the senses); a Uranian dynamis which reflects itself in this pandemic, and vice versa, in the umbilicus mundi where the fecundating virtues of cosmic Love converge9.

The last musical episode I shall mention – passing over those that do not add substantially to what we have learned – takes place at the Fountain of Venus, which commemorates the goddess’s love and mourning for Adonis. Polia and Poliphilo are relaxing with a group of nymphs who alternate singing and dancing with the narration of the rites and mysteries pertaining to the place. The novelty is that after one such recitation, “they sang, with great sweetness and delight, a metrical version of the stories they had told and the things that had occurred” (p. 376/fol. z8v). This suggests an improvisatory practice reflected in the preface to the HP itself, where there are no fewer than three plot summaries: the first in Latin verse, the second in Italian prose, and the third in Italian verse.

If there is one principle of performance practice evidenced in the HP, it is varied repetition. We have seen examples varied by tempo, in the ballet at Queen Eleuterylida’s court; varied by scoring, as with the sailor-nymphs’ alternation of solo, duet, trio, and sextet; by modes, as when the chorus sings in the Ionian, then Polia in the Lydian; and naturally by ornamentation. The background music that accompanies many scenes in the book cannot have been a string of short chansons, as represented in manuscripts or early prints. Never is there a suggestion of playing from the page; every ensemble knows its music already, and like jazz musicians, can vary it indefinitely. Moreover, the musicians of Poliphilo’s world hold to the highest standard in ensemble and intonation, and one cannot believe that Colonna, with his evident connoisseurship, had not heard such music-making and experienced its power over body and soul. But where, and when?

Reading the HP with a musicological eye, it is hard to remember that one is still in the later fifteenth century, so well do the descriptions fit the music of at least a century later. The passage about the sailor-nymphs, quoted above, could be a description of the Concerto delle Donne or the 275“Three Ladies of Ferrara,” virtuoso sopranos whose improvisatory talents were jealously guarded by Alfonso II d’Este for his private delectation. Yet that group was not founded until 1580. The singing in the theater of three choirs of nymphs accompanied by four shawms and four sackbuts remembles the polychoral music that the Gabrielis, Andrea and Giovanni, composed for St. Mark’s basilica, again in the late sixteenth century. The choruses at the Fountain of Venus that simultaneously sing and dance, alternating with narrations of the mysteries, seem straight out of the Florentine Intermedii of 1589, or even Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607). These parallels are merely anecdotal, except in one regard: what they reveal about musical practice in the second half of the fifteenth century. According to the received history of music, the period between the internal dating of the HP (1467) and its publication (1499) was the age of Ockeghem and Busnois, Obrecht and Josquin Desprez. Inevitably it is weighted towards written sources and, within these, to sacred music by Flemish composers. Poliphilo hears none of this, but he hears much more, ranging from the most lavish and professional ensembles down to rustic music on home-made instruments.

The question of where and when Colonna heard it raises biographical issues that are still far from resolution. Could he have witnessed court ceremonies, perhaps in his youth? Only a few documents treat the musical content of such splendiferous events as the Feast of the Pheasant, held in Lille in 1454, with its famous pie out of which the musicians emerged, and the Sforza-Aragona wedding celebrations in Pesaro, 1475, which has distinct parallels to Eleuterylida’s feast10. There must have been many more unrecorded events of this kind. The triumphal processions of the HP, beside their literary origin in Petrarch’s Trionfi, evoke the Florentine carnival parades for which at the end of the century Lorenzo de Medici wrote his canti carnevalesci. Yet the life of a monk in Treviso, and even in republican Venice, does not seem to have offered such opportunities. At all events, the HP gives a glimpse of a richly varied musical environment which, because it has left no paper trail, is lost to us in all but imagination11.

276To sum up, the HP outdoes any Italian epic (whether by Dante, Petrarch, Sannazaro, Ariosto, or the Tassos) in its generous treatment of music and its powers. It celebrates the three traditional types of music: musica mundana, to which the above quotation alludes; musica humana, represented by Poliphilo’s responses and the different states of body and soul which music causes in him; and musica instrumentalis, depicted in its many genres: vocal and instrumental, solo and ensemble, rustic and refined, plain and virtuosic. The correspondence between the three types, sometimes allegorized as Love, is the rationale and foundation of musical magic, as it is of ceremonial magic in general: it performs acts and rituals in the material world in order to attract celestial influences into that which partakes of both heaven and earth: the human being.

Joscelyn Godwin

Colgate University (Emeritus)

1 See J. Godwin, The Real Rule of Four, New York, Disinformation Co., 2004, p. 69-104, for an evaluation of the various claims to authorship; also my review of P. Carusi, Il Polifilo: itinerarium e ludus, Florence, Nerbini, 2015, in Renaissance Quarterly, 70, 2, 2018, p. 748-750.

2 Francesco Colonna, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: The Strife of Love in a Dream, trad. J. Godwin, London, Thames & Hudson, 1999.

3 See especially the two editions that combine a reprint with a volume of commentary: Francesco Colonna, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, ed. G. Pozzi and L. A. Ciapponi, Padua, Antenore, 1980; ibid., ed. M. Ariani and M. Gabriele, Milan, Adelphi, 1998.

4 Johannes de Garlandia, Introductio musice, in E. Coussemaker, Scriptorum de musica medii aevi, Paris, A. Durand, 1865, I, p. 157.

5 See E. Winternitz, Musical Instruments and their Symbolism in Western Art, London, Faber, 1967, p. 86-98, for examples and illustrations of the viola da braccio as substitute for the lyre.

6 Plato, Republic, 399c, trad. G. M. A. Grube, Indianapolis, Hackett, 1974, p. 69.

7 J. Godwin, The Pagan Dream of the Renaissance, London, Thames & Hudson, 2002, p. 61.

8 See M. F. M. Van Den Berk, The Magic Flute; Die Zauberflöte, An Alchemical Allegory, Leiden, Brill, 2004, p. 78, for a comparison of the three portals with parallels in the HP and in the Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz.

9 Translated from Ariani and Gabriele, p. 1051, omitting the page-references to their edition of the HP.

10 See Le Nozze di Costanzo Sforza e Camilla d’Aragona celebrate a Pesaro nel Maggio, 1475, Florence, Vallecchi, 1946.

11 J. Haines, Chants du diable, chants du peuple: Voyage en musique dans le Moyen Âge, Turnhout, Brepols / Tours, CESR, 2018, is a rare attempt to signal the existence and nature of Europe’s lost musical environment. L. Litterick, “On Italian Instrumental Ensemble Music in the Late Fifteenth Century,” in I. Fenlon (ed.), Music in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Patronage, Sources and Texts, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1981, p. 117-130, writes of “a relative dearth of musical activity in Italy” during the fifty years around 1450, followed after 1470 by a “notable upsurge of activity” (p. 125-126). L. Lockwood, Music in Renaissance Ferrara 1400-1505: The Creation of a Musical Center in the Fifteenth Century, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1984, comes closest to describing a real musical world resembling Colonna’s.