The “Un-publication” of Floris and Blancheflour in Early-Modern England

- Type de publication : Article de revue

- Revue : Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes / Journal of Medieval and Humanistic Studies

2019 – 2, n° 38. varia - Auteur : Tether (Leah)

- Résumé : Le roman moyen-anglais Floris and Blancheflour est conservé dans quatre manuscrits médiévaux, dont le célèbre ms. d’Auchinleck. La présence du texte dans des volumes tels qu’Auchinleck et sa publication à travers l’Europe jusqu’au XVIe siècle confirment le succès commercial durable du récit. Cependant, aucun imprimeur anglais ne l’a publié. Cette étude explore les raisons pour lesquelles le jeune secteur de l’édition anglophone a mis de côté ce « coup éditorial ».

- Pages : 367 à 386

- Revue : Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes - Journal of Medieval and Humanistic Studies

- Thème CLIL : 4027 -- SCIENCES HUMAINES ET SOCIALES, LETTRES -- Lettres et Sciences du langage -- Lettres -- Etudes littéraires générales et thématiques

- EAN : 9782406104544

- ISBN : 978-2-406-10454-4

- ISSN : 2273-0893

- DOI : 10.15122/isbn.978-2-406-10454-4.p.0367

- Éditeur : Classiques Garnier

- Mise en ligne : 01/04/2020

- Périodicité : Semestrielle

- Langue : Anglais

- Mots-clés : Floris and Blancheflour, manuscrits, édition, non-publication, Auchinleck

THE “UN-PUBLICATION”

OF FLORIS AND BLANCHEFLOUR

IN EARLY-MODERN ENGLAND

The Middle English Floris and Blancheflour (hereafter Floris) was derived from the aristocratic French version of the tale, Floire et Blanchefleur, and was composed c. 12501. It is thus among the very oldest of romances to have been recorded in English2. As demonstrated by the other articles in this volume, the story of the characters of Floire and Blanchefleur enjoyed widespread and multi-lingual dissemination in the Middle Ages, with versions in most European vernaculars; like these European counterparts, the Middle English Floris seems to have experienced fairly widespread transmission in England. Indeed, the four extant manuscripts all originate from different English regions, though all are confined to the southern half of the country. Unlike many other English metrical romances, Floris does not seem to have made the transition to print – or if it did, it seems not to have survived. The study of lost books in the field of bibliography is not new, of course, and it generally relies upon two methods: either using statistical formulae to make estimates based on surviving books3, or gleaning evidence from medieval/early-modern book lists or inventories4. The former gives interesting, but imprecise results, in that we still cannot say for certain whether a text was or 368was not published, only whether one or the other is statistically likely. The latter, meanwhile, relies on the survival of historical inventories, something which is far from a given. But what happens when the supposition is not that a book has, in fact, been lost, but rather that it never actually existed, as in the case of Floris? How do we satisfactorily explore a text’s “unpublication”? In what follows, I use Floris as a case study for considering whether “unpublication” can be more reliably unravelled through a study of its obverse: to wit, by applying existing methodologies that help us understand why certain texts were published, and then using a process of elimination to determine if and why the unpublished text does not fit that model. Is absence of evidence, in other words, really evidence of absence?

THE MANUSCRIPTS

Two of the Floris manuscripts date to c. 1300; these are Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, MS Gg.iv.27(2) (hereafter Cambridge), possibly from Winchester, and London, British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius D iii (hereafter Vitellius), probably from the South West5. Floris is also found in Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland, MS Advocates’ 19.2.1, a manuscript commonly referred to as Auchinleck (as hereafter) and presumed copied c. 1330-1340 in a London workshop6. The youngest witness is in London, British Library, MS Egerton 2862 (hereafter Egerton), composed c. 1400 in East Anglia7. The text itself seems to have been written in a south-east Midlands dialect8. None of the four extant manuscripts preserves Floris complete: all are imperfect at the beginning, and some are incomplete at the end. In specifics, 369Cambridge lacks its opening 350 lines since the first two leaves are lost, and 824 lines remain. In total, the text would have run to 1174 lines. Auchinleck has lost an entire gathering, the end of which contained the opening of Floris, meaning 350 lines are missing; 861 lines remain, thus the original had 1211 lines in total. Egerton is the most complete, missing a single folio and thus 80 lines from the beginning; 1083 lines of the text remain, so the original ran to 1163 lines. Vitellius is the most defective due to damage sustained in the 1731 Ashburnham House fire; just 445 lines of the narrative survive and only 180 of these are legible9.

I have argued elsewhere that manuscripts occupy a place on a continuum of developing standards for a commercial publishing trade that leads into, and which is importantly not completely suppressed by, the print era10. The Middle English Floris’ witnesses provide precisely the evidence to support that argument. Auchinleck has, for instance, long been studied for its importance as a product of early publishing practice, beginning with Laura Hibberd Loomis’ well-known article of 1942. Loomis posited Auchinleck to be the product of a single professional, commercial bookshop in London11. Scholars such as Ian Doyle and Malcolm Parkes subsequently took up the debate, but concluded that there was no evidence of such singular enterprises in London12. However, more recent scholarship has re-established the fundamental premise of Loomis’ theory, settling on the idea that while a single bookshop may not underlie this book’s production, a collective or consortium of craftsmen operating out of London’s Guildhall seems to have worked in tandem on the manuscript’s creation13 – not dissimilar from what we would recognise 370today as the various departments of a publishing house working together on a product. Floris’ appearance in manuscripts such as Auchinleck, much like its wide transmission across Europe, thus confirms the narrative’s popularity amongst a reading public, and, importantly, its commercial capital as a subject for publication in the Middle Ages.

TRANSITION TO PRINT

Despite the apparent currency of Floris as a text for publication in manuscript books, as indicated in the English context particularly by its inclusion in volumes such as Auchinleck (and indeed Vitellius, as I will discuss below), as well as its fairly wide geographic transmission and dialectal range, when Caxton brought his printing press to London, this text was not one of his chosen subjects for reinvention in print. He printed seven romances that he translated, or had translated, out of French, but neglected entirely English metrical romances14. Given, though, that Caxton’s preference when printing poetry was to stick to the likes of Gower, Lydgate and Chaucer15, and more broadly to texts with national concerns16, his neglect of Floris with its oriental overtones 371is not so surprising. It is more remarkable that the narrative was not picked up by any other early-modern printer in England – not even Wynkyn de Worde, Richard Pynson or William Copland, who made solid businesses out of printing both translated French romances and modernised English metrical romances17.

Even around Europe, however, the sixteenth-century translation of Floire et Blanchefleur from medieval vernacular manuscript to early-modern print was not straightforward. It is only Spain that adapted its medieval vernacular version of the text, Flores y Blancaflor, for early-modern print publication; indeed, between 1512 and 1604, four Spanish publishers undertook to do this18. Given Patricia Grieve’s persuasive case that the origin of Floire et Blanchefleur lies in Spain and the wars between the Moors and the Christian kings, the persistence of the Spanish version of the tale across medieval and early-modern publication in Spain may be self-explanatory19. Elsewhere in sixteenth-century Europe, by contrast, whilst the tale is found printed in France, Belgium, Germany, Bohemia and Italy, these versions are not based on these countries’ own medieval vernacular versions. In France and Belgium, the editions printed in Paris (Michel Fezandat, 1554), Lyon (B. Rigaud, 1570), Rouen (R. du Petit Val, 1594) and Antwerp (Jean Waesberghe, 1561) are a translation by Jacques Vincent of the Spanish version printed by the Cromberger brothers20. The Czech version, printed by Jan Šmerhovský in Prague in 1519, is based on the German translation of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Il Filocolo (which Boccaccio had based on the medieval Italian version of the tale, Cantare di Fiorio e Biancifiore), published by Kaspar Hochfeder 372(Metz, 1499, reprinted 1500, 1530, 1558, 1560, 1562, 1587), which in turn formed the basis for Hans Sachs’ version of the narrative for theatre printed by J. Sartorius (Nuremburg, 1551). It is also upon Boccaccio’s text, rather than the fourteenth-century Cantare, that the Italian print by Ludovico Dolce (Venice, 1532) is based21. Throughout Europe, therefore, translating this metrical romance into print directly from the native medieval vernacular is the exception rather than the rule.

Nonetheless, the prevalence of printed versions across Europe, regardless of the source text used to produce them, evidences that the story of Floire and Blanchefleur remained a “good bet” for publication in many of the territories in which it had been popular in the Middle Ages – but curiously, not so in England. And this despite the fact that various other English metrical romances did find their way into print, including several of Floris’ regular manuscript bedfellows, such as Guy of Warwick, Bevis of Hampton, Sir Degare and Of Arthour and Of Merlin amongst others22.

“UNPUBLICATION” IN ENGLAND

Three initial explanations for the condemnation of Floris to the early-modern slush-pile come to mind. First: something similar already existed in print. Second: the narrative itself was unattractive in some way – perhaps the currency, nature or shape/scope of the subject matter. Third: no exemplars were available. In respect of the first suggestion, that other related or similar narratives were already available, there is only one contender: the English translation of Boccaccio’s Il Filocolo, published as A Pleasaunt Disport of Divers Nobel Personages by Henry Bynnemann for Richard Smith and Nicholas England. The publication date of 1567, however, comes in the second wave of publishing English 373metrical romances, when printers mainly reprinted texts already in print23, so for this volume to have been a factor in not publishing the Middle English Floris seems unlikely. Had Floris been suitable or available for print, it would surely have appeared in the first wave of publishing English metrical romance in the earlier sixteenth century, well before the English rendering of Il Filocolo24.

In respect of the second possibility, that to do with contemporary taste for the narrative itself, we have already noted that Caxton neglected English metrical romances in general and his reasons for doing so have been much studied25. However, the fact that other printers went where Caxton did not dare, and that many reprints ensued, suggests that a reading public existed for English metrical romance, albeit one that was less aristocratic than that for Caxton’s translations of French romance26. Indeed, Graham Pollard reminds us that “[i]n the usual course of trade a book will never be printed until someone thinks it can be sold”27; in short, therefore, metrical romance in print must have been commercially viable.

But if the form or genre of Floris was not the problem, what about its particular narrative content? It is worth noting that the Middle English adaptor had already introduced significant revisions for the medieval anglophone audience. Indeed, the text’s overall length was drastically reduced by the removal of references to French history, and the culling of lengthy dialogue and religious content, to the extent that just one line pertaining to Floris’ conversion, a key narrative moment, remains in the Middle English version. The entire text is thus only about a third of the length of the French urtext28. As a result, any “foreign-ness” that might have been potentially less interesting to a reading public had 374already been suppressed. Furthermore, if the nature of the narrative itself – its romantic subject matter maybe – was not attractive, why then would Boccaccio’s adaptation of the very same narrative, similar in tenor if rather different in detail, have made it to press within a generation, as noted above? Alternatively, Yin Liu has suggested that selection for print may have hinged on a narrative’s main characters, since several Middle English texts contain lists of “typical subjects of romances”, which Liu argues influenced printers’ choices29. There certainly is a discernible bent towards printing romances containing these characters and, admittedly, Floris does not include any of them, but there are other narratives in the same position, such as Eglamour, Sir Degare and Triamour, but which were printed regardless. One could also ask whether the particularly short length of the narrative at c. 1200 lines played a part, but given that the aforementioned Eglamour (c. 1320 lines) and Sir Degare (c. 1100 lines) are of similar length, this also proves difficult to support. The narrative itself, therefore, betrays no particular rationale for why Floris should be any less attractive for print than any other metrical romance, which brings me to the third suggestion – that pertaining to the availability of exemplars.

In his consideration of some of the same arguments for printers’ choices just explored, albeit across the full corpus of printed metrical romances, Jordi Sánchez-Marti has shown that the chances of verse romances being printed are statistically higher if the text has survived in three or more manuscripts, and particularly if there is evidence of London distribution amongst them; printers, he suggests, rather than attempting to give continuity to medieval romance, simply “printed all the romance material they could lay their hands on”30. Of course, Floris is extant in four manuscripts, and at least Auchinleck has a strong London connection, so yet again Floris’ being overlooked seems unusual, but it is perfectly possible that no exemplar of Floris made it into a printer’s hands. Indeed, Margaret Connolly cites precisely “an uneven supply of exemplars” as shaping the choices made by many, if not most early-modern publishers31. I suggest, however, that the compilation of 375the manuscripts in which the text is extant makes this unlikely. As mentioned earlier, Floris is so often copied alongside texts that were printed, that for a manuscript containing it never to have passed through the hands of a printer seems a remote prospect32.

Whilst I have argued for all three possibilities as unlikely, it still has proven impossible to reject any of them entirely. Since looking at Floris itself does not allow me to draw clear conclusions, therefore, and given Sánchez-Márti’s identification of a correlation between manuscript transmission/distribution and the selection of texts for print, perhaps comparing Floris’ transmission history to that of its latterly-printed manuscript neighbours could shed light on the subject.

We have seen that the availability of exemplars often played a role in the selection of which text to print – but it was more complex than simply whether an exemplar was available. Was that exemplar sufficient (e.g. complete or reliable)? Would other source texts be needed to fill in lacunae? Given the increasing efforts of fifteenth-century scribes to create “the seamless book” when copying manuscripts33, as well as the fact that a key corollary of print was to bring coherence and standardisation to the texts published, one might think that a stable written transmission in manuscript could have provided one of several factors in attracting printers to particular texts34. This is not to suggest that printers could not handle the editorial interventions required to reconcile variants across several copies of a given text (I think here of Caxton’s Malory, the text of which is vastly different to that of the Winchester manuscript, known to have been in Caxton’s workshop, and thus proving that Caxton worked 376from at least two, if not more, exemplars35). Rather, a stable written transmission makes for an easier, less labour- and time-intensive (read: less costly) editing process, and texts offering this may thus have been appealing subjects. Guy of Warwick was just such a text, offering a fairly stable version of events across all manuscripts still extant today36, and in all probability also across those available to early-modern printers. Even Bevis of Hampton, which has a notoriously knotty manuscript transmission history, moved steadily towards standardisation in its fifteenth-century manuscripts, which is reflected by the very stable text eventually rendered into print37. It is thus no real surprise to find these texts amongst the metrical romances printed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Guy was, for instance, printed by both Wynkyn de Worde and Richard Pynson between 1497 and 1499, and latterly by William Copland in 1553 and 1556 – all of these are now only extant in fragments. Bevis, meanwhile, was printed between 1499 and 1533 by Wynkyn de Worde, Richard Pynson and Julian Notary, and by William Copland in 1560 and 1565; again, no copy is complete.

Floris, it is true, is marked by far greater textual variation across its four witnesses than these texts. The differing number of lines in each (set out above) is one indicator of this, but more important is the variation in content. All offer roughly the same plot, but differences in detail are marked enough to prove that none is the direct source of the others, though Vitellius, Auchinleck and Egerton seem more connected to each other than does Cambridge to any of them38. Kooper, indeed, argues that at least two distinct versions were circulating within less than fifty years of the original text’s composition39. Such observations have resulted in the suggestion that Floris was written down using memorial practices – through dictation by a performer perhaps. A. B. Taylor, editor of the first modern edition in 1927, was convinced that the text had been transmitted either by means of scribal copies or through dictation from a minstrel 377who had memorised the original40. De Vries, editor of the most recent critical edition, re-evaluated this thesis, but concluded that the variants across Vitellius, Auchinleck and Cambridge were more to do with scribal editing and mechanical error41. However, he acknowledged that Egerton contains variants that can only be explained by some stage, or some stages, of oral transmission42. Most recently, however, Murray McGillivray has pushed again for the argument that the speed of the text’s development can only be explained by an active oral tradition. He underpins this with a convincing analysis of markers of memorisation in the texts, such as repetition, anticipation and long-range transposition of lines43. On the whole, this version of events is now accepted, but even McGillivray’s argument is not without problems, since some passages are uniform across all copies, such as that where Blancheflour’s friend Claris fills her basin with water at the Emir’s palace44. However, if we can accept that at least some of this text’s transmission has its roots in memorisation and orality, with the result that it had a rather exceptional level of transmission variation, then the idea that Floris was not perceived by publishers as an ideal text for translation to the printed medium might seem feasible. Indeed, if we recall the fact that other European printed editions were in fact translations of the Spanish printed version or of Boccaccio (sometimes from Italian, sometimes from other vernaculars), rather than adaptations of the native medieval version, then this might support the notion further. Logically, it would have been easier to translate the text from a recently printed version in a then-current form of language, than to return to (possibly defective) manuscript versions in an archaic language. Where this argument comes undone, however, is when one considers the particularly complex manuscript transmission of a further metrical romance, Of Arthour and Of Merlin, which may also have been influenced by memorial transmission resulting in two distinct versions, ranging from c. 2000-9000 lines45, but which was nonetheless published under the title of A lytel treatyse of the 378byrth and prophecye of Marlyn by Wynkyn de Worde in c. 1499, 1510 and 1529, though only the 1510 edition survives complete46.

A question arises, therefore – did printers even care about reconciling a text for print across several manuscript versions? A. S. G. Edwards thinks not:

It is only rarely that one finds much interest in problems of textual variation between such witnesses […] There was no explicit attempt by the early print editors to explain the ground on which one witness was felt superior to another or to suggest why a particular manuscript should be used at one point but not at others47.

Edwards further argues that having different versions was usually only useful when filling in lacunae – printers, in other words, were more concerned with “shoring up” the integrity of a single exemplar than with reconciling differences across several versions48. This said, there is evidence that some printed books were subjected to deliberate “critical editing”, such as Wynkyn de Worde’s 1498 The Canterbury Tales, which Boffey shows to have been based on several exemplars, among which were both manuscript and printed items49. Meanwhile, Rhiannon Purdie has argued that memorial transmission underlies not just the manuscript transmission, but also the sixteenth-century printing in Scotland of King Orphius (a text closely related to Sir Orfeo)50. In sum, therefore, just as it was impossible to prove or exclude any of the initial three possibilities for “unpublication”, the same is true here. The notion that it was for the lack of a stable written transmission that Floris was condemned to the printer’s slush-pile is possible, but not probable; there are simply too many examples of printers willing to use texts with complex transmission histories, both written and oral, as subjects for print. However, a process of elimination has clearly determined that Floris was, in principal, a viable subject, which begs the inevitable question: how can we actually be sure it was not printed?

379PUBLISHED OR “UNPUBLISHED”?

Given the extant state of printed witnesses to texts such as Guy of Warwick, Bevis of Hampton and Of Arthour and Of Merlin, it is only through fortunate transmission that we know anything at all of these texts in print. For example, Wynkyn’s Guy is only known from a single leaf. Had Floris been printed, one might expect there to be some reference to it, but it is conceivable that one existed without our knowledge. The Stationers’ Register, for instance, which was the means used by the London livery company of Stationers to record publishers’ rights to publish given works in England, only has records from 1554 onwards, and some of the Register was destroyed in the 1666 Great Fire of London51. There are also examples of texts known to have been printed, but which have not survived. For example, Carol Meale has argued for a printed Libeaus Desconus due to its listing alongside other “ungracious bokes” known to have been printed in Richard Hyrde’s translation of Vives’ De institutione feminae Christianae52. Meale has also made the case for a lost printed Parthenope of Blois on the basis of its inclusion in an inventory of printed books belonging to Edward Stafford53. And even if Floris did not make it to print, did someone perhaps consider it, only later to discard it for some reason? The manuscripts’ possible use as printers’ copies, therefore, needs to be ruled out, since this has not previously been done.

The list of known printers’ copies for English books printed between 1500 and 1640 is very short. Just 26 are listed in Moore’s 1992 audit54, none of which is one of those containing Floris. Printers’ copies are usually identified by annotations on the folia, such as casting-off marks (the counting of lines to set the type by formes), editorial emendations or paragraph marks; additionally, printing 380ink smudges, which typically appear much blacker than marks made in the ink used by scribes, can be another sign of use as a print exemplar55. I shall therefore search the manuscripts for these types of indicators.

MANUSCRIPT EVIDENCE

Vitellius’ fire damage renders it practically unusable; it has just 26 folia, and what is left of Floris is on fol. 6r-8v. As a product of medieval publication, Vitellius, undamaged, would be remarkable. A 1696 catalogue, indeed, explains that it contained a unique combination of texts in English, Latin, French, including a now lost Anglo-Norman copy of Amis and Amiloun56. However, in Vitellius’ current state of mutilation, there is no evidence that it was ever used as a printer’s copy.

Cambridge is also a slim set of folia. This single quire of 14 leaves was once bound in with the works of Chaucer now in Cambridge’s MS Gg.iv.27(1), but the two sections are not of the same original enterprise. The sixteenth-century owner/collector, Joseph Holland, may have bound the two together either to supply lost passages to the mutilated Chaucer or because the nature of its contents – entertaining romances – was not dissimilar. It is, however, also possible that the two were bound together even before Holland owned it57. The two were unbound from each other under the supervision of Henry Bradshaw, Cambridge University Librarian between 1867 and 188658. Floris now occupies fol. 1r-5v, and textual corrections are few and in a contemporary hand, possibly even 381the same as that of the main text. There is, in short, no evidence of use as a printer’s copy.

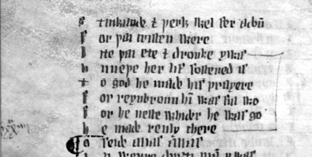

Auchinleck has, of course, been extensively studied, and the likelihood of discovering new evidence seems remote. Indeed, in Floris, present on fol. 100r-104v, there is nothing of note. However, a re-examination of the entire manuscript reveals that another narrative, Reinbrun (a continuation of Guy of Warwick), has received some curious markings which have so far gone undetected. On fol. 168r-169v, a reader has marked up a series of verses with square brackets, as if to indicate where they stop and start. The verses marked in this way number 34, and appear to have been counted by the same reader, as evidenced by the “xxxiiij” written in a late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century hand on fol. 169v (see Figure 1). For what purpose these markers were included is difficult to fathom – they could, for example, be as arbitrary as someone counting out verses to read aloud. It is just plausible, though, that they are casting-off marks of some description. There is, however, no evidence that Reinbrun was ever printed – though, of course, that does not necessarily mean it was not. In the absence of any alternative explanation, therefore, whilst I cannot conclude for certain that Auchinleck was at some point in the hands of a printer, these marks mean that the possibility cannot be excluded.

Fig. 1 – Detail showing bracket around verse and marginal “xxxiiij” in Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland, MS Advocates’ 19.2.1, fol. 169v; reproduced by kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

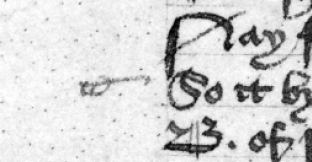

382In Egerton, Floris is on fol. 98r-111r, and several of the texts in the manuscript have received a range of early-modern markings, which have not previously been noted. For example, there are paragraph or line space marks in a late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century hand throughout, as would be expected to designate the layout for a target text. These are visible on at least 23 folia (see an example in Figure 2), and probably more originally, but the heavy cropping of some margins means such evidence has been lost59. These marks are identical with those found in Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 638, a manuscript known to have been a printer’s copy and in which these paragraph marks (on fol. 1r-4v) correspond to line spacing in the associated printed edition60. Additionally, there is the regular appearance of what seem to be signature marks in the lower right-hand corner of the recto of several folia in the manuscript. Again, these are in a late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century hand, which may be the same as that providing the line space marks. The marks are set in the standard format for signature marks in early prints, with a majuscule Arabic letter (or in the latter part of the manuscript, an Arabic numeral or minuscule letter – see below) followed by a Roman numeral between i and iv61. These could be benign signs of an early-modern reader paginating the manuscript, but the sequence does not map to the structure of one leaf per signature mark; specifically, signature marks are not included on all folia and, even taking into account the various known folio losses, as well as the marks likely lost through the heavy cropping of margins, it is impossible to reconstruct a page-to-page sequence based on the signature marks still visible – the numbers of folia between signature designators are typically too large. This said, the sequence is clearly systematic, since the Arabic letters appear in alphabetical order: the first visible mark is an O on fol. 34r and the sequence runs through P (fol. 40r and 41r), S (fol. 64r and 65r), U/V (fol. 80r and 81r) to X 383(fol. 89r). Thereafter, the marks are more heavily rubbed and almost impossible to read, but seem to move to the format of either an Arabic numeral or minuscule letter followed by a Roman numeral from i to iv. The irregular sequence of these marks, coupled with the fact that some system underlies them, means it is just possible that the marks indicate which folio in the source text – that in the manuscript – would correspond to which page in this target text – that in the printed book. Given the Roman numeric sequence of i-iv, furthermore, this printed book would probably have been in quarto, the preferred format for metrical romance in print62. Two such marks are even found on the folia containing Floris (fol. 101r and 107r, see Figure 3). Finally, there are some ink smudges on fol. 23v and 79r that appear blacker than the ink of the main text, but these are small and difficult to identify for certain as made by printing rather than scribal ink. However, if these various pieces of evidence are taken together, it becomes just conceivable that this manuscript, of whose provenance we otherwise know little, may once have been in a printer’s shop.

Fig. 2 – Example paragraph mark in London, British Library, MS Egerton 2862, fol. 68v; © British Library Board (Egerton 2862 f68v).

384

Fig. 3 – Example signature mark in London, British Library, MS Egerton 2862, fol. 107r; © British Library Board (Egerton 2862, f107r).

There is, then, at least some evidence to suggest the use in a printer’s workshop of two of the four manuscripts containing Floris. Both manuscripts are assumed to have been privately owned/commissioned, which might give rise to the argument that they would not have been available to printers, but in fact, privately owned books were often rented/loaned to printers as exemplars63, so even if Auchinleck and Egerton were in private ownership, this does not necessarily mean they were not available as print exemplars at some point. Indeed, given the very nature of Auchinleck as a particularly important book product, so famous even Chaucer may once have held it64, it would seem peculiar if it had not at some point piqued the interest of an early printer. The problem, of 385course, is that no corresponding printed book seems to exist for the texts in either manuscript, so proving this remains impossible. Yet, considering the fragmentary state of other printed metrical romances, and the mark-up evidence from these two manuscripts, I cannot entirely rule out that they did not at least pass through a printer’s hands, or indeed that some initial planning of translation to print was not undertaken, albeit abandoned for some reason, such as running out of capital to fund the project or the business failing, both of which were common occurrences in the early days of print65, or perhaps for some other reason66. Indeed, something similar seems to have occurred in relation to another unprinted verse romance, the Stanzaic Morte Arthur, a manuscript fascicule of which is known to have been purchased (and was at one time bound) together with one of Ipomydon B, the latter of which served as the exemplar for Wynkyn de Worde’s edition of c. 152267.

In sum, I can conclude neither why Floris was not printed nor, indeed, whether it was printed at all (or even just considered for print) – at least not beyond the balance of probabilities. However, this should not be seen as a disappointing outcome. As we will recall, I asked at the outset of this study how “unpublication” could most satisfactorily be explored, and the approach I adopted of comparing Floris to known indicators of viability for publication has borne useful fruit. The various possibilities for Floris’ likely consignment to oblivion by early printers – from the lack of a stable textual transmission history, to the unavailability of exemplars, and to the contemporary taste for different kinds of subject matter or form –, remain plausible explanations as to why Floris might have been passed over. To answer my initial question as to whether absence of evidence equals evidence of absence, therefore: no, it certainly does not. Still, in investigating the many possible reasons why something 386did not happen, it falls to the scholar, first and foremost, to prove that it actually did not. The manuscript evidence of Floris presented and investigated in this article demonstrates that just because there is no extant printed book, we should not assume that there never was one, nor indeed the idea of one. Rather, we have little choice but to accept the tantalising possibility that Floris might not have been “unpublished” after all. Once we embrace this, as I contend we should, we have at our disposal a powerful tool for the study of other “unpublished” texts during the medieval and early-modern periods68.

Leah Tether

University of Bristol

1 E. Kooper, Floris and Blancheflour: Introduction, Sentimental and Humorous Romances, Kalamazoo, TEAMS, 2005, accessible on the TEAMS website.

2 Ibid.

3 Such as E. Buringh, Medieval Manuscript Production in the Latin West: Explorations with a Global Database, Leiden, Brill, 2010. For a more cautious approach, see T. Haye, Verlorenes Mittelalter: Ursachen und Muster der Nichtüberliefun mittellateinischer Literatur, Leiden, Brill, 2016.

4 A. Hill, “Lost Print in England: Entries in the Stationers’ Company Register, 1557-1640”, Lost Books: Reconstructing the Print World of Pre-Industrial Europe, ed. F. Bruni and A. Pettegree, Leiden, Brill, 2016, p. 144-159, at p. 145. More generally, see the Medieval Libraries of Great Britain website.

5 F. C. De Vries, Floris and Blauncheflur: A Middle English Romance edited with Introduction, Notes and Glossary, Groningen, V. R. B., 1966, p. 3-5; see also Kooper, Floris.

6 De Vries, Floris, p. 1-3; see also Kooper, Floris. The most up-to-date debate on Auchinleck can be found in The Auchinleck Manuscript: New Perspectives, ed. S. Fein, York, York Medieval Press, HB 2016, PB 2018, esp. D. Pearsall’s chapter “The Auchinleck Manuscript Forty Years On”, p. 11-25.

7 De Vries, Floris, p. 4-5; see also Kooper, Floris.

8 De Vries, Floris, p. 39.

9 Ibid., p. 8-12.

10 L. Tether, Publishing the Grail in Medieval and Renaissance France, Cambridge, D. S. Brewer, 2017, esp. Ch. 1.

11 L. H. Loomis, “The Auchinleck Manuscript and a Possible London Bookshop of 1330-1340”, PMLA, 57, 3, 1942, p. 595-627.

12 A. I. Doyle and M. B. Parkes, “The Production of Copies of the Canterbury Tales and the Confessio Amantis in the Early Fifteenth Century”, Medieval Scribes, Manuscripts and Libraries: Studies Presented to N. R. Ker, ed. M. B. Parkes and A. G. Watson, London, Scolar Press, 1978, p. 163-210.

13 T. Shonk, “A Study of the Auchinleck Manuscript: Bookmen and Bookmaking in the Early Fourteenth Century”, Speculum, 60, 1, 1985, p. 71-91; T. Shonk, “A Study of the Auchinleck Manuscript: Investigations into the Process of Book Making in the Fourteenth Century”, PhD dissertation, University of Tennessee, 1981, p. 31-49; T. Shonk, “Paraphs, Piecework, and Presentation: The Production Methods of Auchinleck Revisited”, The Auchinleck Manuscript, ed. Fein, p. 176-194; J. Mordkoff, “The Making of the Auchinleck Manuscript: The Scribes at Work”, PhD dissertation, University of Connecticut, 1980, p. 18-59; T. K. George, “The Auchinleck Manuscript: A Study in Manuscript Production, Scribal Innovation, and Literary Value in the Early 14th Century”, PhD dissertation, University of Tennessee, 2014, p. 150-191; D. Pearsall, “The Auchinleck Manuscript”; D. Pearsall, “Literary and Historical Significance of the Manuscript”, The Auchinleck Manuscript: National Library of Scotland Advocates’ MS. 19.2.1 with an Introduction by Derek Pearsall & I. C. Cunningham, London, Scolar Press and The National Library of Scotland, 1977, p. vii-xi, at p. xiii-ix.

14 R. S. Crane, The Vogue of Medieval Chivalric Romance During the English Renaissance, Menasha, George Banta, 1919, p. 2-4.

15 Perhaps because of the issue of maintaining poetic form when translating poetry out of another language; see N. F. Blake, “William Caxton: His Choice of Texts”, Anglia, 83, 1965, p. 289-307, at p. 298. There have been other suggestions, too; for the most up-to-date summary see J. Sánchez-Martí, “The Printed Transmission of Medieval Romance from William Caxton to Wynkyn de Worde, 1473-1535”, The Transmission of Medieval Romance: Metres, Manuscripts and Early Prints, ed. A. Putter and J. A. Jefferson, Cambridge, D. S. Brewer, 2018, p. 170-190 – with thanks to Ad Putter for letting me see a proof.

16 Richard Garrett describes Caxton’s translational practice, particularly where out of French, as designed to “serve an English national project”; R. Garrett, “Modern Translator of Medieval Moralist? William Caxton and Aesop”, Fifteenth-Century Studies, 37, 2012, p. 47-70, at p. 49; see also, amongst many examples, W. Kuskin, Symbolic Caxton: Literary Culture and Print Capitalism, Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame Press, 2008, p. 194-195 inter alia; J. Martin, “Making the Caxton Brand: An Examination of the Role of the Brand Name in Early Modern Publishing”, MPhil dissertation, University of York, 2010, esp. p. 93-97; T. Atkin and A. S. G. Edwards, “Printers, Publishers and Promoters to 1558”, A Companion to the Early Printed Book in Britain 1476-1558, ed. V. Gillespie and S. Powell, Cambridge, D. S. Brewer, 2014, p. 27-44, at p. 28-29.

17 Crane, The Vogue, p. 4-11.

18 Arnao Guillem de Brocar (Alcalá de Henares, 1512 †), the Cromberger brothers (Seville, c. 1516-1532, c. 1532, c. 1533), Felipe de Gunta (Burgos, 1562, 1564) and Juan Gracián (Alcalá de Henares, 1604).

19 P. E. Grieve, Floire et Blanchefleur and the European Romance, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 46-50.

20 For a discussion, see Grieve, Floire et Blanchefleur and the European Romance, p. 21-22.

21 There is also the French translation of Boccaccio’s version, printed by Denis Janot in 1542; see in this volume G. Burg and A. Réach-Ngô, “Transmettre l’histoire de Floire et Blanchefleur en France au xvie siècle”: positionnement sur le marché éditorial et stratégies de publication”.

22 See the full list in J. Sánchez-Martí, “The Printed History of the Middle English Verse Romances”, Modern Philology, 107, 1, 2009, p. 1-31, at p. 6-7, 13.

23 That is, c. 1550-1570; Sánchez-Martí, “The Printed History of the Middle English Verse Romances”, p. 13, 16-17.

24 The first wave was c. 1499-1530; Sánchez-Martí, “The Printed History”, p. 6-7.

25 Such as his developing a taste for continental narratives following his time in Burgundy (Crane, The Vogue, p. 3-4); see also the overview in A. S. G. Edwards and C. M. Meale, “The Marketing of Printed Books in Late Medieval England”, The Library, 6th series, 15, 1993, p. 95-124, at p. 118-119.

26 Crane, The Vogue, p. 9.

27 G. Pollard, ‘‘The English Market for Printed Books: The Sandars Lectures 1959”, Publishing History, 4, 1978, p. 7-48, at p. 9.

28 Kooper, Floris. For a detailed analysis, see G. Tasseto, “Translating and Rewriting: the Reception of the Old French Floire et Blancheflor in Medieval England”, PhD dissertation, Ca’Foscari University of Venice, 2014, esp. Ch. 5.

29 Y. Liu, “Middle English Romance as a Prototype Genre”, Chaucer Review, 40, 2006, p. 335-353, lists reproduced on p. 340-341, 348-350.

30 Sánchez-Martí, “The Printed History”, p. 23-26.

31 M. Connolly, “Compiling the Book”, The Production of Books in England 1350-1500, ed. V. Gillespie and D. Wakelin, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013, p. 129-149, at p. 132-133; Ralph Hanna terms it “exemplar poverty”: R. Hanna III, “Miscellaneity and Vernacularity: Conditions of Literary Production in Early Modern England”, The Whole Book: Cultural Perspectives on the Medieval Miscellany, ed. S. G. Nichols and S. Wenzel (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), p. 37-51, at p. 47.

32 Printed texts appearing in the same manuscripts as Floris are (A = Auchinleck; E = Egerton): Eglamour (E), Sir Degare (A, E), Guy of Warwick (A), Bevis of Hampton (A, E), Of Arthour and Of Merlin (A), King Alisaunder (A), Sir Triamour (A), Richard Coeur de Lion (A, E). Some of these texts may have been in Cambridge, but only 14 leaves are extant. Similarly, we cannot know the original contents of Vitellius, though no latterly-printed English metrical romances were present in 1696: T. Smith, Catalogus manuscriptorum Bibliothecae Cottoniae, Oxford, Sheldonian Theatre, 1696, p. 90.

33 A. S. G. Edwards, “Chaucer from Manuscript to Print: The Social Text and the Critical Text”, Mosaic, 28, 4, 1995, p. 1-12, at p. 5.

34 J. A. Jefferson and A. Putter, “Introduction: Forms of Transmission of Medieval Romance”, Transmission of Medieval Romance, ed. Putter and Jefferson, p. 1-14, at p. 7.

35 L. Hellinga and H. Kelliher, “The Malory Manuscript”, The British Library Journal, 3, 2, 1977, p. 91-113.

36 On Guy’s transmission, significant oral influence is ruled out by R. Spahn, Narrative Strukturen im Guy of Warwick: Zur Frage der Überlieferung einer mittelenglischen Romanze, Tübingen, Gunter Narr, 1991, p. 30-33.

37 See J. Fellows, “Bevis: A Textual Survey”, Sir Bevis of Hampton in Literary Tradition, ed. J. Fellows and I. Djordjević, Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2008, p. 80-113, esp. at p. 92-96.

38 De Vries, Floris, p. 9.

39 Kooper, Floris.

40 A. B. Taylor, ed., Floris and Blancheflour, a Middle English Romance edited from the Trentham and Auchinleck MSS, Oxford, Clarendon, 1927, p. 15.

41 De Vries, Floris, p. 7.

42 Ibid.

43 M. McGillivray, Memorization in the Transmission of the Middle English Romances, New York, Garland, 1990, Ch. 3.

44 As pointed out in Kooper, Floris.

45 O. D. Macrae-Gibson, ed., Of Arthour and of Merlin, 2 vols, EETS OS 279, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1979, vol. 2, p. 52.

46 Sánchez-Martí, “The Printed History”, p. 6-7; see also O. D. Macrae-Gibson, “Wynkyn de Worde’s Marlyn”, 6th series, 1980, p. 73-76.

47 Edwards, “Chaucer”, p. 5-6.

48 Edwards, “Chaucer”, p. 6.

49 Boffey, “Manuscript to Print”, p. 16.

50 R. Purdie, “King Orphius and Sir Orfeo, Scotland and England, Memory and Manuscript”, Transmission of Medieval Romance, ed. Putter and Jefferson, p. 15-32.

51 A. Hill, Lost Books and Printing in London 1557-1640: An Analysis of the Stationers’ Company Register, Leiden, Brill, 2018, p. 1-2.

52 C. M. Meale, “Caxton, de Worde, and the Publication of Romance in Late Medieval England”, The Library, 6th series, 14, 1992, p. 283-298, at p. 296.

53 Meale, “Caxton, de Worde”, p. 285-286, 289-290, 297.

54 J. K. Moore, Primary Materials Relating to Copy and Print in English Books of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Oxford, Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1992.

55 Boffey, “Manuscript to Print”, p. 15-17; Moore, Primary Materials, p. 11; R. E. Stoddard, Marks in Books: Illustrated and Explained, Cambridge, Houghton Library, Harvard University, 1985, p. 1-2.

56 Smith, Catalogus, p. 90; see also G. Griffiths and A. Putter, “Linguistic Boundaries in Multilingual Miscellanies”, Middle English Texts in Transition: A Festschrift Dedicated to Toshiyuki Takamiya, ed. S. Horobin and L. Mooney, York, York Medieval Press, 2014, p. 116-124, at p. 120-121.

57 Tasseto, “Translating and Rewriting”, p. 79-84.

58 R. A. Caldwell, “Joseph Holand, Collector and Antiquary”, Modern Philology, 40, 4, 1943, p. 295-330, at p. 299.

59 Fol. 28v, 31v, 33r, 33v, 34r, 36r, 40r, 40v, 42v, 43v, 49v, 61v, 66r, 68v, 77r, 85v, 89v, 116v, 117r, 117v, 121v, 124r, 129v.

60 As shown in respect of fol. 1v of MS Bodley 638 and its correspondence to sig. B3v-B4r in Wynkyn de Worde’s 1531(?) edition of John Lydgate’s The complaynte of a louers lyfe; Moore, Primary Materials, Plates 1 and 2.

61 These marks are found on 14 folia in total: fol. 34r, 40r, 41r, 47r, 64r, 65r, 80r, 81r, 89r, 101r, 107r, 116r, 125r, 130r.

62 Sánchez-Martí, “The Printed History”, p. 26.

63 Caxton, for instance, mentions being loaned a better exemplar by a gentleman for the second edition of The Canterbury Tales in his preface, as reported by Connolly, “Compiling the Book”, p. 131.

64 L. H. Loomis, “Chaucer and the Auchinleck MS: Thopas and Guy of Warwick”, Essays in Honor of Carleton Brown, New York, New York University Press, 1940, p. 111-128 suggests Chaucer may have owned Auchinleck, but this is convincingly refuted by C. Cannon, “Chaucer and the Auchinleck Manuscript Revisited”, The Chaucer Review, 46, 1&2, 2011, p. 131-146.

65 See, for instance, J. H. M. Taylor, Rewriting Arthurian Romance in Renaissance France, Cambridge, D. S. Brewer, 2014, p. 45.

66 The Stationers’ Register, indeed, provides evidence for the period of the second wave of printing verse romances (c. 1550-1570) that several printers took out licences to publish various verse romances, but these seem, for reasons unknown, not to have been published, or at least not to have survived; Sánchez-Martí, “The Printed History”, p. 13-14.

67 J. Sánchez-Martí, “Wynkyn de Worde’s Editions of Ipomydon: A Reassessment of the Evidence”, Neophilologus, 89, 2005, p. 153-163, at p. 157.

68 Such as King Horn and Amis and Amiloun, both of which were compiled alongside Floris in manuscripts and which, on the face of it, were similarly viable subjects for print. King Horn is in Cambridge (fragment); Amis and Amiloun is present in Auchinleck and Egerton, and an Anglo-Norman version was once in Vitellius (Smith, Catalogus, p. 90).